The Devil Wears Miuccia Prada

GRWM for the Fall of American Democracy

Unfortunately, this post is too long to appear in full in your inbox. I don’t know where it will cut off in the email version, but it will be available online. See you there!!!

Consuming any amount of news over the past few weeks has been nothing short of horrifying, and there’s a part of me that feels it’s irresponsible to run a newsletter like this and not talk about it.1

But that part of me is, candidly, also the one that’s been in fight or flight mode more often than not lately and has a hard time remembering the world doesn’t stop spinning just because the president posted racist AI-generated content to his official social media accounts. In a way, always having a sensationalist reaction to the current administration plays into its authoritarian fantasies: we talked about this briefly here before, but it’s important to remember that

anyone who studies authoritarianism, a political system that depends on propaganda, corruption, machismo, and violence, is well acquainted with the parade of sociopaths, sycophants, petty and grand criminals, and zealots who flourish in lawless environments where the performance of power is everything and the leader is elevated to a semi-divinity. In authoritarian states, ridiculousness often competes with brutality for center stage (X).

It is essential to stay informed at times like these, but it is not always imperative to spend our every waking moment talking and thinking about every breaking news headline. I say all of this not with confidence but because I regularly need to remind myself that the only party to benefit from hyperfixating on the spectacle of the Trump Administration is the administration itself.

Instead, today we are discussing something that the current moment in time is informing: we’ve covered style, fashion, and the forces acting upon both numerous times on E4P before, because I think it’s one of the best ways to talk about self-expression and identity as well. However, I wanted to go even further and speak with someone who has taken up studying fashion history at a time when I am understandably craving conversations about any history at all.

This week, following the recent fashion weeks across the globe, Zoe Eisenstein returns for her hat-trick installment to talk about the politics of fashion, what she’s learned from studying a highbrow topic during a moment of anti-intellectualism, and whether or not fascists have good taste in clothes.

Zoe is a Bay Area-based fashion hobbyist who, since her first E4P feature, has become in tune with Real Housewives culture. Zoe works in advertising by day and spends her nights marathoning The Gilded Age while scrolling 129 pages deep into “vintage Prada” keyword searches on Vestiaire Collective and The Real Real. Zoe loves cats and dogs (equally), swimming in clear blue bodies of water, and Miuccia Prada.

Fashion, But For People Who Are Extremely Hot and Brilliant

I was recently reflecting on my conversation with Bhavya from earlier this year and, with it, the idea of not doing something out of a fear of frivolity. I was thinking about this a lot in connection with some of the thoughts I shared in the introduction, how some things are seen as unserious if they don’t speak to the seriousness of being alive in the world today.

But I don’t think that’s right or even very fair—as Bhavya explained in May, daydreaming and actively using your imagination muscle is a very human and very essential behavior. The more I reflect on it, I also think that this reasoning (that things must be serious in order to matter right now) is something I’ve been fed quite a lot recently via algorithms. Whether or not it’s a universal fact, it factored into how I approached this conversation.

As such, I wanted to kick off the piece by asking Zoe:

Emily: Some people might find a conversation about fashion at a moment of crisis, like what we’re living through in America right now, to be frivolous. Can you speak to some of your favorite ways that fashion and politics have and continue to intersect?

Zoe: Honestly, I would probably say that nothing about fashion has ever been frivolous! As I’ll get to later, what we wear is inextricably tied to class, social positioning, and in/out groups, but it’s also at the center of many prescient conversations about consumption culture, sustainability, and the actual impact of our insatiable hunger for fashion.

Fast fashion companies have expertly camouflaged the suffering that goes into fashion where consumers can’t really see its impact. The clothes are produced by severely underpaid prison laborers, migrant workers, and the urban poor in impoverished places with bad workplace safety regulations, using plastic textiles that are destroying the planet.

The consumer is across the world and does not have to think about or see the exploited worker or the polluted river. This literal and metaphorical “distance” between consumer and producer helps us justify our fashion habits, because it makes the cost less tangible to us. Even I still buy fast fashion garments despite knowing this!

There’s also the fact that in this political moment, few subgroups and communities have “a look,” for lack of a better word. If you had long hair in the United States in the ‘60s, it probably meant you were someone who was against the Vietnam War. And if you were a Brit who wore tartan, studs, safety pins, and fetishwear in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, it probably meant you were an anarchist who frequented The Clash or Sex Pistols shows.

Styles like long hair and grungy rocker fits became more popularized and mainstream as time went on, to the point where in the ‘70s, even conservative dudes wore their hair long. But in those moments when people with unpopular beliefs needed help finding each other, this shared sartorial language helped people locate their communities.

In the age of digital culture and the internet, the mainstreaming process is so rapid that these subcultures hardly have time to develop before they’re totally mainstream. And that’s why nowadays you could absolutely see a dude wearing carpenter pants, a Carhartt tee, and a beanie at either a DSA meeting in Brooklyn or homeschooling his kids at his Utah homestead, and it makes sense in either context.

John Waters has this amazing quote about this phenomenon that I’m constantly referencing, where he says “When I was young there were beatniks. Hippies. Punks. Gangsters. Now you’re a hacktivist...But there’s no look to that lifestyle! Besides just wearing a bad outfit with bad posture. Has WikiLeaks caused a look? No! I’m mad about that. If your kid comes out of the bedroom and says he just shut down the government, it seems to me he should at least have an outfit for that.”

The way that Zoe approaches talking about fashion deeply fascinates me because what she’s doing here (as she often does on Instagram) is situating the individualism of style in larger conversations about cultural trends. As Miranda Priestly so decreed in the Cerulean Monologue from The Devil Wears Prada, our personal taste is largely informed by the directions society and culture started moving in long before it reached us on a personal level.

With this, I wanted to ask Zoe:

Emily: Based on your research, how would you describe the relationship between fashion history and sociology to someone who has never thought to look at fashion that way before?

Zoe: Fashion is and always has been a class marker, a signifier of in-groups and out-groups, and a method of communicating your values, tastes, and cultural identities without words.

Georg Simmel, who wrote one of the foundational texts in fashion sociology posited that fashion can only exist in a society if the concept of class also exists. I believe he meant “class” in the sense of social ranking, but I also view it as something that distinguishes one particular group from another. Fashion tells us so much about the gender roles, class relationships, and lives of the people of a particular era.

For example, trends from fashion history like tall powdered wigs, foot-binding, farthingales, cage crinolines, and big dress bustles are quite clearly marked as class-exclusive because they signify a life of leisure. Women with bound feet weren’t physically able to do manual labor; a heavy, dusty wig would slow down a farm worker; and people living in crowded cities couldn’t reasonably take up the amount of space that massive, crinolined skirts necessitate. Kings, queens, and titled nobility wore these fashionable garments in their portraits because they signified a life of leisure and excess that the rural or urban poor could never access. They were allowed to take up space and stay immobile.

But as I alluded to earlier, I don’t understand Simmel’s concept of class as purely relating to wealth. Societies that prioritized social hierarchy and title—like Elizabethan England—had sumptuary laws reserving some garments, textiles, and materials for titled elites only. Even if a wealthy, titleless person like a banker could afford to wear these materials, doing so put them at risk of incurring fines or getting into legal trouble.

There’s also class as social capital: for example, most celebrities aren’t necessarily the wealthiest billionaires or heads of state, but in the modern era, we often look to pop-cultural figures like actors and singers for fashion inspiration.

And finally, my favorite, the idea of class as in/out groups: how people distinguish themselves aesthetically to find like-minded people who belong to their class, like punks, or hippies, or even me in high school, where I was always looking for fellow Tumblr-obsessed girls who wore American Apparel, Doc Martens, and Arctic Monkeys shirts.

As we were putting this piece together, I kept thinking back to our brief conversation about the Hemline Index and its validity. To refresh: there was a long-running theory that when the American economy is doing well, skirts get shorter, but when the economy is doing poorly, skirts get longer again.

While the argument for the Hemline Index, much like a Shein top, does somewhat fall apart if you look at it too hard, there is something to be said about the argument that mainstream fashion trends often reflect the political climate du jour. But is it a one-sided thing, in that politics shapes fashion? Or is the fashion the more important indicator in the equation?

I asked Zoe:

Emily: Do you think fashion is reflective of current politics, or do politics impact fashion and our consumption more?

Zoe: I definitely think it’s a bit of both, but I think the sociopolitical moment we’re in is so pressure-filled that I’d have to say current politics are impacting fashion a bit more than fashion is simply reflecting current politics.

One big trend I can point to on this topic is the resurgence of 1980s opulence in fashion. TheRealReal’s 2025 Resale Report featured an entire section titled “From Reagan to Now: Maximalism Returns” which showcased the popularity of search terms on their site that align with the 80s-era trends. Fashion publications are telling their trend-conscious readers to look out for the 80s resurgence, and 80s-inspired looks, colors, and silhouettes were on a lot of SS ‘25 and FW ‘25 runways.

In this political moment, I think we’re all feeling the callback to the 80s. The denial of trans rights (and even the denial of the very existence of trans people as a protected group) recalls the government’s absolutely cruel indifference to the AIDs epidemic. “Protect the children” and “tough on crime” rhetoric is being used to demonize immigrants, the LGBTQIA+ community, and people of color. The economy has almost never felt more trickle-down and income inequality is staggering.

Plus, Trump, obviously. The ‘80s were his heyday. When he was plastered all over Page Six! Back then he was just a bad landlord and an obnoxious annoyance to New Yorkers, and now he’s…well. You know.

Speaking of Trump, I wanted to know:

Emily: Do fascists have good taste in fashion?

Zoe: In my opinion, historically, they do not. According to Simmel, fashion is the balance between conformity and individualism within that class-based society. In an oppressive society where individualism gets you punished or makes you stick out unnecessarily, that element of the equation is pretty much removed in its entirety, which makes it hard to have fashion at all, much less good fashion.

With that being said, it’s critically important for me to note that limiting gender expression to very narrow notions of masculine/feminine creates really bad fashion. I think playing with gendered expectations of dress is such a great way to take risks with fashion. Some of the most well-known developments in fashion history have a lot to do with shirking these gendered notions of dress.

Most people know about the rise of boyish silhouettes and hairstyles for women in the 1920s (the flappers) and about how pants became popular among women in the 1960s and 1970s as feminism popularized and more (white) women entered the workforce.

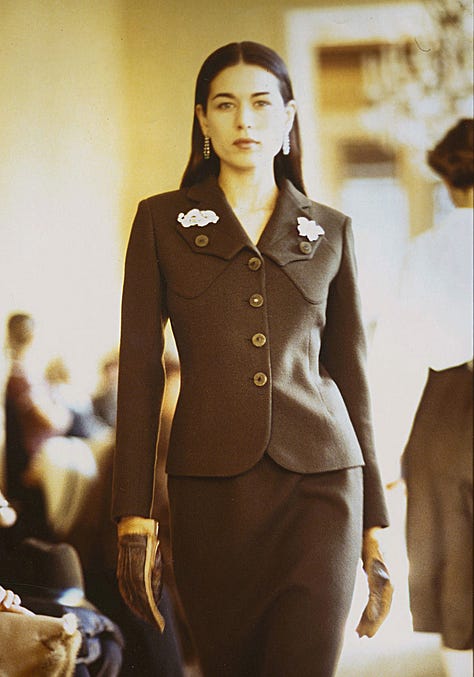

One of my all-time favorite runway shows, Prada FW 1988, is about this very topic. The fashion YouTuber Bliss Foster has a really amazing video about it. Under Italian fascism, Mussolini created this group of Italian government officials called the Ente Nazionale Della Moda who decided what clothing suitably reflected ideal Italian values. And shocker! Everything was extremely gendered.

Zoe (cont.): FW ‘88 was Miuccia Prada’s first collection as the Creative Director of Prada. Miuccia grew up in Italy under fascist rule and has publicly stated that she felt she couldn’t dress how she wanted to as a child. She was also a member of the Italian Communist Party, a feminist, and has a PhD in political science, so a lot of her work reflects that background.

With this collection, she essentially pulls all the typical silhouettes and looks from the Mussolini era and makes fun of all of them in some way or another. Importantly, one of the only garments with a more “traditional” feminine shape is a skirt-suit recreation of the Italian fascist military uniform. The original silhouette was tailored to make soldiers look broader and more masculine, with huge pecs. Miuccia tailored the suit to emphasize the model’s hips and breasts.

Essentially, she took the uniform of the “ideal Italian male” and made it girly, which was a huge fuck-you to fascist ideas about gender and dress.

In a piece analyzing the historical context of Prada’s FW’88 show, the writer remarked that Miuccia’s “innovative approach to fashion demonstrates that clothing can be more than just an expression of personal style; it can be a way of communicating ideas, challenging social and political rules, and questioning the conventional perceptions of beauty and good taste.” That piece, much like Zoe in her above response, does such a lovely job of explaining the level of thought and craftsmanship that went into making the collection as significant as it was.

In the only Carrie Bradshaw reference I’ll make in a piece about fashion, I couldn’t help but wonder what happens to artistry like this when we stop thinking and stop creating for ourselves?

There’s an Addison Rae Joke to Be Made in Here Somewhere

In today’s least shocking news, I am largely anti-AI in all use cases (I’m sorry, but wasn’t sentient artificial intelligence the big, scary villain in so much sci-fi dystopian art when we were growing up??? Are we not supposed to be, like, at least a little terrified of it???), but especially so when it comes to art.

It was an unplanned coincidence, but last week, news broke that an AI-generated actress named Tilly Norwood had real, human talent agencies vying to represent her. Unpacking that could be its own piece, but it did make me think about how present AI already is, even in creative spaces. I couldn’t square that fact with what little I do know about fashion design and production, so I wanted to see if Zoe had any thoughts on the matter:

Emily: Tactile artistry is essential to every stage of fashion, from the design to the actual assembly of an item, and to wearing and displaying it. How do you see high fashion changing, if at all, in the age of AI—and regarding people using AI to create art specifically?

Zoe: I honestly know very little about this and am extremely eager to hear about what people who work in sustainability/international labor would have to say about it, but I would hope that if AI is this unstoppable force that we’re hearing it is, it could be used in a climate-conscious way (like that would ever happen) to help mitigate some of the pain and suffering that goes into fabricating clothing.

I think we’re all aware of the cost of fast fashion—unsafe working conditions for garment workers, labor violations, etc. If people demand low-cost garments and don’t really care if others suffer to make them, it seems to me that we may be able to create lower-cost garments by removing the element of human suffering altogether.

But obviously, that creates another issue, which is that we’re displacing labor from people who might need those jobs. And that doesn’t solve fervent overconsumption or the fact that fast fashion companies vastly overproduce garments and textiles in ways that are irreparably polluting the planet.

Unfortunately, the way AI is being used in fashion presently is to assist in the creative process, which I think is deserving of criticism. Call me old-fashioned, but I think art should be reflective of the human spirit. There is no shortage of artists or creatives in this world, and I think everyone’s time is better spent in pursuit of creative endeavors than in doing menial labor under unsafe conditions.

There was a huge backlash when Hillary Taymour of Collina Strada used AI to generate the patterns on her fabrics for her Baggu collab. And the dress company Selkie has also come under scrutiny for using AI-generated patterns on their dresses while branding themselves as a sustainable “slow fashion” brand.

Funny enough, there was a second AI term that came to mind when Zoe and I began building this piece. Anti-intellectualism is not a new phenomenon by any means, but living under a Trump presidency at the same time AI is exploding, media literacy is declining, and social media has altered our attention spans, has allowed it to become all the more commonplace. Anti-intellectualism

refers to a mistrust and rejection of modern intellect, knowledge, and academia. This school of thought manifests in three categories: religious anti-rationalism, populist anti-elitism, and unreflective instrumentalism. Religious anti-rationalism depends on emotionally charged arguments of religious reasoning over logic, while anti-elitism favors a rejection of elite individuals, such as professors and the institutions they represent. Unreflective instrumentalism denies seeking knowledge unless it can generate profit (X).

When framed this way, you can clearly see why anti-intellectualism is having its diva moment right now. Much in the way I considered how a conversation around fashion might not read as necessary right now, I view the world of fashion as something that is deeply intellectual and elitist in many ways. Zoe hit on this earlier when she talked about the relationship between classism and clothing, as did Emmanuel Llorente when we discussed the history of queerness in fashion. There is so much critical analysis that goes into building collections and trends and style that is inherently antithetical to anti-intellectualism.

With all this in mind, I wanted to know what drew Zoe to this research and what she has taken away from all of it:

Emily: You’re not in the world of fashion professionally, but you care so deeply for it and speak so eloquently about it. What has studying fashion—a highbrow topic being analyzed in a highbrow way—brought to your life, especially in a moment of anti-intellectualism?

Zoe: Not to say something so nonspecific, but I honestly think it has given me a better understanding of the world in a lot of ways. Seeing the way that trends develop, when they become popular, and even the speed at which they cycle tells me a lot about the world we’re living in politically, economically, and socially.

While I’m certainly beating a dead horse and recalling the thousands of think pieces spawned by this trend, I really do think that the cottagecore/tradwife trend was a signifier that a lot of people were itching for the oppressive comfort of traditional gender roles. I am NOT saying I think that’s a good thing, but I do think that the flowy, hyper-feminine silhouettes and the emphasis on “women’s roles” and the “divine feminine” spoke to a desire among some people for a really strong delineation between what is masculine and what is feminine.

Even the whole “mob wife” trend—which in retrospect attracted more of a backlash than a legitimate popular following—was really about this idea of femininity (albeit a different kind than the tradwife) where a woman is dressed in these luscious, sexy, luxurious clothes and fabrics that are paid for by a husband whose money is abundant and whose work is dangerous. It’s darker than the tradwife, it’s sexier and more sinful, but it is, above all, as sharply gendered as the tradwife is.

Trends come from a desire to signify something—whether it’s that you’d rather be churning butter than at your office job or that you’re trying to dress like that cool person who would rather be churning butter than at their office job. But who we look to for fashion inspiration says a lot about the kinds of tastes and values we aspire to, because we dress the way we want to be perceived by the world.

When you understand style not just as an individual choice, but as a method of communication or as something emblematic of your values, it makes it more interesting to examine higher-level trends and select garments for your own wardrobe.

I don’t mean to undersell Zoe’s point here by any means; in fact, I think it’s strengthened by the acknowledgement that it’s something we’ve already covered in today’s piece. It’s sort of comical, actually.

Ask Not What You Can Do For Fashion, But What Fashion Can Do For You

I feel like we’ve only just started scratching the surface of this conversation, in that there are so many more lenses through which I want Zoe to explain fashion history. For now, though, I’m content just to ask:

Emily: What is the best lesson you’ve learned from interacting with fashion on a more studied level?

Zoe: That Lady Gaga is a genius. Kind of kidding, not really. There is no other creative or pop star that I know of who has used fashion, personal style, and iconography to signify her beliefs and cultural knowledge so legibly and effectively.

I was too young to recognize it at the time, but in her early career, Gaga’s allyship with the queer community—at a time when that kind of allyship was not considered popular or cool—was signified with SO MUCH more than just outright statements of solidarity. She communicated it through her clothing, through her music videos, through her lyrics.

I think the reason she has such a large queer fanbase (aside from her outright allyship) is because queer people could catch details in her dress and her music and her videos and know that her allyship was legitimate and came from a place of deep understanding—it was not just lip-service.

I rewatch the “Alejandro” music video constantly and find something new every time. She is so detail-oriented and smart.

Emily: What is one thing you’ve learned about fashion that you wish other people knew, too?

Zoe: Really, I just want everyone to know about and appreciate Elsa Schiaparelli. To me, Elsa Schiaparelli is the thinking-man’s Coco Chanel. They were rivals because Coco Chanel was incredibly competitive and did not want other women to succeed in fashion. While Coco was collaborating with Nazis, Elsa Schiaparelli was hanging out with writers like Jean Cocteau, artists like Salvador Dalí, Picasso, and Man Ray, and trendsetting patrons of the arts.

I appreciate her daringness in creating unique, avant-garde garments, like her Skeleton dress with ribs on the outside from 1938 (!!!), and the iconic Lobster dress she made in collaboration with Dalí. She was also responsible for popularizing her signature shade “shocking pink”—without which we wouldn’t have Marilyn Monroe’s iconic shocking pink Gentlemen Prefer Blondes dress, or even something like Valentino’s hot pink AW’22 collection.

Her work frequently dissolved boundaries between art and fashion when no other dressmaker was doing anything of the sort. Maison Schiaparelli went bankrupt back in 1958 and it makes me sad to think Elsa died without seeing the massive resurgence of her brand under Daniel Roseberry, who has also done an excellent job paying tribute to Elsa’s original designs and house codes.

In my head, I’m a Schiaparelli girl, which is to say this newsletter really needs to start blowing up so I can get the kind of name-brand recognition that gets you invited to Fashion Week shows and sent items from the houses. As of right now, though, it’s actually fiscally unwise for me to even look at anything Schiaparelli.

But I digress. Zoe obviously knows her salt about fashion history, but as we close out the most recent fashion week season, I wanted to ask:

Emily: What developments in the fashion world are you most excited about right now?

Zoe: As this month of fashion weeks draws to a close, I’m still buzzing about Louise Trotter’s debut at Bottega Veneta.

In the past two years, at least 16 brands have introduced a new Creative/Artistic Director, and Louise Trotter is far from the biggest name of the bunch. Big promotions for designers like Jonathan Anderson, Mathieu Blazy, Pierpaolo Piccioli, and Demna generated the most buzz ahead of fashion week(s), so it’s been refreshing to see that the most well-received debut came from a bit of an underdog.

To close out today’s piece, I wanted to end on a question I asked with no foresight into how Zoe was going to respond to the first question in this section, but sheer delight at the full circle moment of it all:

Emily: Walk walk fashion, baby?

Zoe: Work it move that bitch crazy

Walk, walk fashion baby

Work it

I’m a free bitch, baby

That felt as good as when the outfit you planned in your head actually looks amazing in reality.

Thank you so much to Zoe for always being game to yap with me!!! I love it when conversations I’ve been wanting to have finally come to fruition, and I can’t sing her praises enough, especially after all the scheduling kerfuffles I put her through!!!

It, of course, being Charlie Kirk’s death and the insane aftermath, Jimmy Kimmel’s removal and return to air, Trump’s 73-minute speech to military officials, the ongoing government shutdown, ICE’s activities in Chicago that are somehow more chilling than their other incredibly chilling activities, and, like, 200 other things that have already been lost to the 24-hour news cycle ether.