One of my favorite things to do here at E4P is expand on conversations we’ve already started to have. In Blair Baker’s most recent visit, we talked about the shifting presence of body standards and pressures in both the media and our lives. Then, in the comment section, one of today’s guests suggested a way to continue our chat.

So we did.

Today, I’m joined by Olivia Milloway (of commenting fame) and hat trick E4P superstar Liz Pittenger to talk about unpacking anti-fat bias, what their relationships with their bodies currently look like, and how they’ve each reached a point of radical self-love.

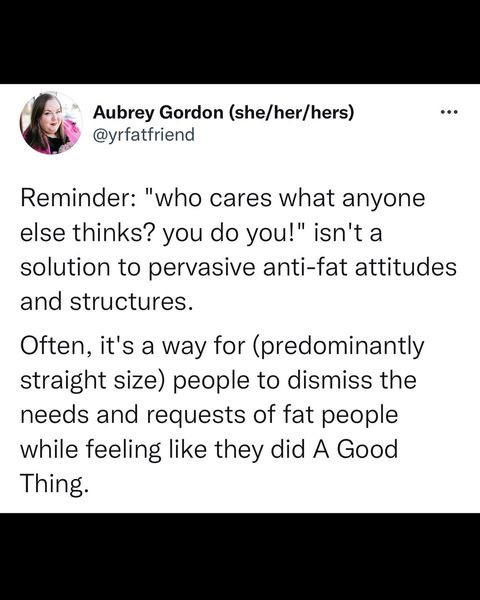

Before we get started, I should probably answer the question, “Wait…what is anti-fat bias?” The more frequently used term for what we’re covering today is fatphobia but after talking with Olivia and Liz—and consulting one of their icons, Aubrey Gordon—it became clear that we should stray away from giving that word any more airtime.

As Gordon explained in a 2021 piece for Self,

Phobias are real mental illnesses, and conflating them with oppressive attitudes and behaviors invites greater misunderstanding of mental illnesses and the people who have them…People who hold anti-fat attitudes don’t think of themselves as being “afraid” of fatness or fat people. Fatphobia denotes a fear of fat people, but as the most proudly anti-fat people will tell you readily, they aren’t afraid of us. They just hate us. Calling it a “fear” legitimates anti-fat bias, lending credence and justification to the actions of those who reject, pathologize, and mock fat people, often without facing consequences for those actions.

Instead, activists and medicinal professionals alike have shifted to using the term anti-fatness, which the National Institutes of Health define as “a negative attitude toward (dislike of), belief about (stereotype), or behavior against (discrimination) people perceived as being ‘fat.’”

Now that that’s covered, let’s dive right in.

Olivia Milloway (she/her) graduated from Emory University last spring and spent the past year living and working in Acadia National Park in coastal Maine. She jumped on the sourdough baking trend three years late and loves cooking almost as much as she loves eating—her favorite earrings are mini fork and knife set. The day this very newsletter comes out, Olivia is flying to Panama City, Panama for a year of marine biology research and freelance science journalism. Future E4P on fishies, Emily??

Liz Pittenger (she/her) also graduated from Emory University last spring and works at a non-profit in downtown Atlanta where she is a community first responder addressing the needs of people experiencing quality of life concerns with the hope of keeping folks out of jail. She LIVES for the warm Atlanta weather (hello spring!!) and tries to spend as much time as she can outside going on long walks and runs, or laying in the park reading. She also loves practicing yoga, listening to podcasts, and going out to fun dinners with her friends.

Before we begin…

Olivia: I want to explain my relationship with fatness. I’m a cis queer white woman and have lived in a thin body most of my life. I was diagnosed with an eating disorder two years ago and since I started treatment, my body has changed a lot and I’ve started using the word “fat” to describe myself. I wear mostly straight-sized clothing and sometimes plus-sized, depending on the brand.

Fatness and body size are a spectrum and I fall on the smaller side, benefiting from size privilege, and I don’t face the discrimination and harassment that many fatter people do. As such, I look towards the writing and experiences of fatter people for learning and unlearning about anti-fat bias.

Liz: Like Olivia, I am also a queer white woman who has shifted in and out of fitting into “straight-sized” clothing throughout my life. While I don’t necessarily identify as fat, I describe myself as a “big bitch.” In fact, one of my clients recently told me that I could definitely beat him in a fight because I have “tree trunks for legs”—I took that as a compliment. My body has definitely changed in the last couple of years. As I’ve gained more weight, I’ve also grown in admiration for people fatter than me—this shit is not for the weak!

That being said, the more I learn about fatness, the more I understand fatness as an identity and fat people as a marginalized population. I have not been marginalized due to my weight and, while this isn’t contingent on identifying as fat, it is a part of many fat people’s life experiences. Like Olivia, I learn from my fat parasocial besties about the implications of anti-fat bias.

Is the Anti-Fat Bias in the Room With Us Right Now?

Towards the end of “Are the Body Standards in the Room With Us Right Now?” we talked about the value body neutrality can have in comparison to the toxic optimism that often dominates the body positivity movement. Yet, while this line of thinking and living had worked for Blair, I confessed that

I’m also not sure I want to feel neutral about my body—I certainly don’t want to hate it and I don’t want to be pressured to feel positive about it when I’m not, but is wanting to feel good in my body so much to ask?

After years spent oscillating between hating my body, forcing myself to fake kindness to myself, and scrutinizing every single detail of my physical form, I’m tired of doing everything aside from just existing. Yet, as I shared, body neutrality still felt like a shade too cold for me. Gratefully, Olivia reached out to reveal that body neutrality had also not been a fit for her and, as a result, she turned to Sonya Renee Taylor’s concept of radical self-love.

In an effort to continue this journey of reshaping conversations around my body and everyone else’s, I wanted to unpack this approach as well as how Olivia and Liz have developed their own relationships with body image by first dismantling anti-fat bias.

To start, I asked:

Emily: When did you realize you were harboring anti-fat bias?

Olivia: This is an embarrassing confession, especially in today’s economy, but there’s this podcast that changed my life called Maintenance Phase. Hosted by supreme overlord of independent podcasting Michael Hobbes and my fat fairy godmother, Aubrey Gordon (who I’ll be talking a good bit about today), the show debunks diet trends and wellness myths from the keto diet to Moon Juice.

There was an episode of the show that came out a few years ago where I first really learned what anti-fat bias was: a form of systemic discrimination that causes demonstrable harm to fat people.

At the time, I thought the #AerieReal campaign could cure diet culture and if only people loved themselves and embraced body positivity, we could all get along and bake cakes out of rainbows and smiles and we’d all eat it and be happy. But after learning how anti-fat bias operates, I started seeing it everywhere—both in the world and in myself.

While I maintained I was supportive of fat people and didn’t treat them any differently than thin people, I felt deep shame when my pants didn’t fit me anymore and was terrified of gaining weight (that, dear reader, is anti-fatness).1

Liz: I feel like I’ve been doing work to understand diet culture and anti-fat bias for a couple of years through listening the podcast, Maintenance Phase, and reckoning with my almond mom childhood and disordered eating habits. However, the thing that really jolted me into understanding my own relationship with anti-fat bias was hearing someone else call me fat.

Even though I was already on my body-acceptance journey, when I heard this I was literally devastated—like lie in bed, scroll on TikTok, listen to Phoebe Bridgers on single-song repeat devastated. When I was done having my big emotions, I reflected and thought to myself, “Why are you so concerned about being perceived as fat? And also what does that mean about how you feel about fat people?”

These thoughts and feelings about my own body are the embodiment of anti-fat bias has lived in me for as long as I can remember and how I started my journey of truly unlearning anti-fat bias.

When Liz shared this, I remembered that some of my earliest cohesive memories were when I was picked on for my weight on the school bus. I couldn’t have been more than ten and, yet, my body became a weapon that people could use against me. Feeling bad about my body was just something I did then because, from then on, it was ingrained in me that the worst thing you could be at nine years old, and therefore at any age, was bigger than the other girls.

It has taken me my entire life since then to unpack and unlearn comments that were so unmemorable to these kids, and only maybe in the past year or two have I started to do so without building my self-esteem up from the thought that at least I didn’t peak in high school or have a receding hairline in my early twenties (body shaming is body shaming, even if I was doing so in private, so now I just build myself up from the fact that at least I didn’t peak in high school or college…listen, a hater isn’t unbuilt in a day).

But this all made me want to circle back to what Liz and Olivia both said about how they viewed other fat people. Often, the people we are cruelest to are ourselves but, almost equally as often, our self-hatred can leak out and shade how we view others.

I asked:

Emily: How does anti-fat bias intersect with other forms of discrimination?

Liz: Anti-fat bias makes fat people a marginalized population, leaving them vulnerable to many types of discrimination—from employment, dating and interpersonal relationships, to medical discrimination. My professional and academic experience primarily has to do with the criminal legal system and policing, so I’ll take anti-fat bias from this perspective.2

In July of 2014, Eric Garner was murdered by NYPD officers for allegedly selling loose cigarettes. He was held facedown on the concrete in a chokehold while he repeated, “I can’t breathe,” until he died. When the officer was put on trial to determine if he would lose his job (the officer was not charged criminally by the Staten Island District Attorney), the officer’s defense team blamed Garner for not surviving this attack—they said if Garner was not fat, he would have survived.

This incident serves as a clear example as to how anti-fat bias intersects with racism and medical discrimination. Policing and the legal system are ingrained with anti-Blackness and act as white supremacist project (a tale as old as time). Black people are seen as inherently dangerous and criminal in the eyes of white supremacy, and fatness is layered onto this discrimination as physical size often determines how threatening an individual is perceived to be. Eric Garner was unfairly seen as a big, scary, Black man threatening the officer.

Beyond the unwavering anti-Blackness displayed in this brazen murder, the officer’s defense exemplifies medical discrimination towards fat people. Listening to fat activists like Jessamyn Stanley and Aubrey Gordon has exposed me to the ways in which medical professionals will ignore and dismiss the health concerns of fat people and advise them to lose weight in lieu of treating their ailment.

These acts of neglect and violence send the implicit message that fat (and Black) people deserve mistreatment because of their bodies.

Emily: Liz, how has your job informed your relationship with your body? How has what you've learned from working in a social justice space shaped how you view yourself?

Liz: My job has forced me to work on myself and my relationship with myself a great deal. I want to sustainably work in this field and be the best clinician that I can. I cannot do that if I am not taking care of myself. My work takes a huge emotional toll on me because of the amount of systemic neglect and violence I bare witness to on a daily basis.

I realized very soon into my first social work internship that taking care of myself is absolutely a priority in this work, in fact, I cannot do my job at all if I am not attending to my physical and emotional needs. Beyond that, seeing people in their worst moments makes me unbelievably grateful for the ways in which I have the privilege of taking care of myself and my body. So many people don’t have access to a laundry machine, shower, or clean water—forget about opting into exercise when you don’t have a car or a safe place to sleep. I think reframing the little tasks that I do for myself and my wellbeing as privileges makes them easier to do.

Facing the ugliness of the institutions that serve to oppress my clients makes me even more certain of the radical self love we owe to ourselves. When society and institutions all tell us to hate ourselves, that we’re undeserving of care and humanity, and that we’re only valuable as a producer of capital, we have to push back with radical and unconditional love for ourselves.

I see unwavering love and light in each of my clients which makes me even more certain that these same things exist in me. On the hardest days, you still have to love yourself if nothing else but to spite everything that tells you not to.

One thing Blair and I discussed that I wanted to make sure I covered with Olivia and Liz is how the pressure of adopting anti-fat biases and behaviors is often placed the most on women and femmes—as is the shame of fatness, the fear of fatness, and subliminal desire to be anything but fat.

With this in mind, I asked:

Emily: Why is there such a stigma around the word fat and why is it most typically used to demean women's and femme's bodies in particular?

Olivia: The word fat is a neutral descriptor of someone’s body, just like tall or short, but is often used and perceived as an insult because of the negative meaning we ascribe to it. To many, fat is synonymous with wrong, unlovable, lazy, or disgusting. Because fatness is seen as fundamentally undesirable, I think the term is leveraged against feminine presenting bodies because their socially-determined value is proportional to their desirability.

Using the word fat to describe myself has been affirming, and continuing to use the word in a neutral or positive way strips it of its power. I would never call someone fat if they first don’t use the word to identify themselves, as everyone has a different relationship to the word and it continues to be used to harm people.

Liz: Patriarchy also teaches femme people that to be small is to be good, to be a better woman, to be more feminine, etc. As a femme person, I believe that patriarchal femininity is linked to how much you can shrink yourself to make room for men. I believe that being fat and loving your body can be an expansiveness that fights directly against patriarchy. Also how are we going to fight the big bad patriarchy hungry and weak??? BOO!

The Quiet Part of My Brain Still Hasn’t Gotten the Memo

Circling back to the question at the center of this which, for me, has always naively been, “When will someone give me the key that unlocks all the love I want to have for my body?” I wanted to know what it was like to toggle between each of the body approaches. As someone who, for all intents and purposes, failed at both body positivity and neutrality, I wanted to know what it takes to get to the point of radical self-love—the one effort I had yet to try.

I asked Liz and Olivia:

Emily: In your words, what is the difference between body positivity, body neutrality, and radical self-love? Why does the one you pick best suit you?

Olivia: These first two approaches to making peace with your body work at the individual level. In my understanding, body positivity is about fostering a positive self-image regardless of mainstream beauty standards whereas body neutrality or acceptance is about focusing on what your body can do for you rather than on how it looks.

Radical self-love, which was coined by Sonya Renee Taylor, author of The Body is Not an Apology, envisions “a world free from the systems of oppression that make it difficult and sometimes deadly to live in our bodies.” Like the others, it’s about the self, but unlike the others, it sees “the self is part of the whole.” Radical self-love is about loving your own body and liberating yourself from body shame so that you may love the bodies of others, too.

I think one key difference is that radical self-love takes an intersectional approach to self-love that aims for justice for all bodies. Another is where this self-love comes from—not from how your body looks (positivity) or what your body can do for you (neutrality), but because we all have an innate dignity that is worthy of self-love.

I’ve tried each of these on for size over the years and have settled on striving for radical self-love.

Emily: What are your opinions about each of these three approaches?

Olivia: There are some definite drawbacks to the first two. The body positivity movement has been commercialized and has lost its teeth, centering thin, white, cisgender, able-bodied people—something you covered in Blair’s original newsletter.

Body neutrality still hinges on the usefulness of a body—how it can move or what it can do—as the determining factor that gives it value, rather than centering every body’s inherent dignity regardless of ability. And, body positivity and body neutrality only work internally. They don’t reframe your relationships to other bodies of different shapes, sizes, and abilities.

I think the biggest failing of these frameworks is that they only work to improve the lives of people who benefit from size privilege and aren’t harmed by anti-fat bias. Aubrey Gordon sums it up in “A draft agenda for fat justice”:

“The more I navigate the language of body positivity and fat acceptance, the more I feel the precise edges where both fall short. Positivity and acceptance insist upon individualized solutions to systemic problems. Yes, loving and caring for our bodies are good things. But I cannot love my body enough to escape widespread employment discrimination. I cannot self-confidence my way through health care that can see all of my size and none of my symptoms. And I cannot muster enough loving my curves to ensure that I will not endure the staggering cost and public humiliation of being escorted from a plane—even when I have a second seat.”

This is where, I think, Sonya’s model of radical self-love can sit hand-in-hand with fat justice.

Liz: I completely support anyone’s use of body neutrality. Everyone is on their own journey of exorcizing the brain worms we inherited from diet culture and societal anti-fat bias. Whatever you have to do to care for yourself is a-ok with me. However, I do think that body neutrality falls short, especially in the greater project of ✨liberation✨.

To me, body neutrality relies on the idea that there is a less desirable body that you are trying to distance yourself from, that you just have to live in this meat suit and not hate it. To this I ask: what do you hate? If it’s the fatter parts of your body, why do you hate them? Who is in the room with you right now? (A ghost of patriarchy? A ghost of capitalism trying to sell you a juice cleanse/tummy tea/detox pill?)

Don’t get me wrong—I have been there. The only thing that could get me to radical self-love is understanding that loving myself wholeheartedly is a huge “fuck you” to all the systems that are put in place to make me—and all people with marginalized identities—smaller, to subjugate us. Giving into this self-hatred means that I also feel that same way about other people. Huge core values of mine are justice and freedom. I need to embrace and love myself so I can truly love and embrace everyone else.

Before we segue into the next section of our conversation, I wanted to pause to mention the existence of mid-sized bodies. While the fat acceptance community does not fully embrace the term (something you can read more about in this fantastic article by Casey Johnston in Vice), it’s a word and a community that has made me feel notably comfortable over the past three years.3

One thing I’ve heard a number of times from individuals on social media and in person, particularly from those who are mid-sized or fat, is that it is incredibly exhausting to spend so much mental energy thinking about our bodies. To someone who doesn’t share this experience, it’s easy to think, “Well…just stop then.”

But the problem is that the thinking—the spiraling, the projecting, the assumption of how other people are thinking, too—is all so reflexive and instinctual. As Johnston writes, “fat activists say, rightly, that it’s a privilege to not have to think about one’s body as ever being an imposition.” Whether I want to be or not, my body and the world’s perception of it are always on my mind.

This is the core issue I keep returning to in my conversations with Blair, Liz, and Olivia, as well as in my own quest to make this incessant thinking more bearable with positivity, neutrality, and radical self-love. But I wanted to know, maybe for the first time, if there’s a way to try to turn off these thoughts altogether—a “Well…just stop then” solution, if you will.

I asked Olivia and Liz:

Emily: How can we get to a place where we just stop thinking about our bodies all the time?

Olivia: I really wish I knew how to answer this. I think personally, I’ve come to a place of budding peace and self-love through a lot of work of unlearning anti-fatness and cultivating a loving relationship with my body, but I don’t think I have any advice to give other than don’t give up.

Liz: It’s so hard! I think that you’re always going to spend some time thinking about your body. My advice is to work diligently on reframing your thoughts about your body to loving, kind, and accepting thoughts. Seek gratitude for your body and how amazing all the little neurons firing at every moment.

When that doesn’t work and you just want to take a deep breath, my advice is to plug up the thoughts with a podcast or audiobook. I love listening to The Body is Not an Apology audiobook and the Dear Jessamyn podcast.

Emily: What do you do now on days that you don't like your body?

Olivia: If I’m having a bad body day, I put on something comfy (this winter, my savior was the Athleta fleece lined yoga pant). I try to be as kind as I can to my body—some days that means going to the gym and others it means playing Cooking Mama on my iPad.

Journaling through my feelings, too, can help me figure out where these bad feelings are coming from: Is anti-fatness rearing its ugly head? Am I repeating lies about femininity and desirability? Do I just need to drink some water?

I also lean on my support system of folks who have been in the trenches with me. I might tell Liz I’m feeling negatively toward my body and ask her if she’s in a good place to hold some of my thoughts and work through them with me. A lot of negative thoughts, especially related to body image and food, can be triggering, and I always like to ask for consent before sharing. Comfy clothes, iPad baby games, journaling, and talking it through with someone who understands where I’m at and shares my values helps soothe me when I’m having a rough body day.

Liz: On these days, the first thing that I do is check my Clue period tracking app because hormones really go crazy—they’re normally my self-hatred culprit. If I can rule out the PMS loathing spiral (or even if I can’t), I’ll spend extra time pampering myself. I love skincare and all the little serums—side note but I feel so ancestrally connected to womanhood when I do this, like bitches have always LOVED a potion—so I’ll spend a long time putting on my little tinctures and face masks and lotions. I also like to go on a super long walk and spend some time thinking about what I actually need.

Similarly to Olivia, I’ll ask myself: When was the last time I had alone time? When was the last time I texted my besties? Did I drink last night (hangxiety is also crazy)? And, most importantly, what can I do to make myself feel better right now?

I also try to revert my bad thoughts back to my values and remind myself about how my thoughts might be coming from a place of implicit and explicit biases. It’s important to have grace for yourself in these moments while also interrogating these thoughts.

It’s not your fault that you think them but it is your responsibility to deal with them.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Obviously, we were never going to solve all of the problems re: anti-fatness here today—nor were we ever going to be able to solve them all within ourselves because, shockingly, E4P isn’t actually a real therapy dupe—but I wanted to feel like we were at least starting to make progress in that direction.

I asked:

Emily: How did you go about changing your attitudes to fatness and your own body?

Olivia: My first memory of body shame was when I was seven years old wearing my first communion dress to school for some Catholic school event. I wore a little white dress with spaghetti straps and a silk white jacket. The jacket was uncomfortable so I took it off, and my teacher made me put my gym uniform over it to cover up my arms. I guess it was too immodest for a seven year old and didn’t follow our strict dress-code. I remember burning with shame about my arms and having to cover them up with a sweaty gym shirt.

There’s that saying that if you repeat a lie enough it starts to sound true, and I think that’s how I came to think that fatness was undesirable and unlovable. So, I’ve just been repeating the truth to myself—there’s nothing about fatness that’s inherently undesirable or unlovable—even on days when I’m struggling to believe it about myself. I only felt shame about my body once that teacher told me I should.4

I’ve been changing my attitudes about fatness and my body in a similar way—except I’m the authority figure telling myself that there’s nothing to be ashamed of about my arms look today, the same way there was nothing to be ashamed about the way my arms looked when I was seven.

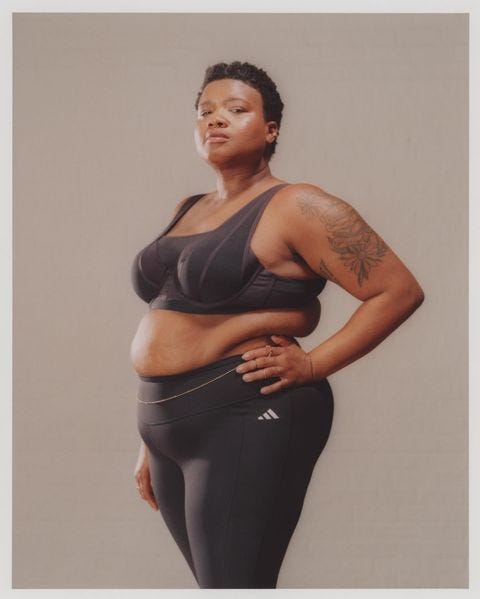

Something that’s helped alongside this un-brainwashing campaign is to flood my feed with fat people just living their lives. Fat bodies simply aren’t shown in the media, and the act of seeing, of normalizing fat bodies, is a great place to start. The Adipositivity Project (this site is NSFW) has a similar mission: it “aims to promote the acceptance of benign human size variation and encourage discussion of body politics…through a visual display of fat physicality. The sort that's normally unseen.”

And, finally, I took the advice of another fat fairy godmother of mine, Jessamyn Stanley, who says to look at yourself naked, familiarize yourself with yourself, and feel your body without fear.

Emily: How do you take care of your body in intentional ways? What has that done for your relationship with it?

Liz: I think a huge lesson that I’ve learned is that I have to work with myself and my imperfections. I have to find workarounds to do what is best for me. We can’t all be the TikTok clean girl of our dreams—you have to make it easy for yourself to take care of yourself. Once I figured out how to work with myself to take care of me, I learned to trust myself. I’m definitely still on this journey but I think that building trust in myself by listening to my body and meeting my needs has been amazing for my relationship with it.

For example, I feel so much better when I am active and get moving in one way or another every day. I’ve built up trust with myself so even if I miss a day, I’m never hard on myself because I know that I will do what I need to do the next day. I also am an undiagnosed ADHD girlie where my default is often paralysis, so I have little post-it notes up on all my mirrors and in my room reminding me what I can do to take care of myself depending on my energy level.

Little things like that have really improved how I feel about my body and have really given me a great sense of gratitude for myself.

Only YOU Can Prevent Internalized Anti-Fatness

Through these conversations with Blair, Olivia, and Liz, and after looking through all of the content that makes all of us feel validated and good in our skin, I’ve arrived at a very weird realization: I feel bad for people who, in this economy, still choose to hold onto their anti-fat biases.

There never has been, nor will there likely ever be in our lifetimes, a shortage of anti-fat commentary and content from people who have no business being in anyone else’s. Yet, it’s embarrassing to be that person. Honestly, it’s really embarrassing to be a bigot in any way, shape, or form, but looking at the anti-fat gym rats that Drew Afaulo annihilates in her TikToks or Candace Owens who is “a proud fat shamer” or some of the kids who once bullied me on the bus who I know have not and will likely never change their ways, I really can’t help but feel anything other than sorry for them. I mean, anyone who exists in this world with all of the things that are actually terrifying and still thinks fatness is one of the top things to fear…do you not feel shame?

But enough about them and back to us, the real stars of the show.

How can we all start or continue the process of dismantling our internalized anti-fat bias? The answer, both fortunately and unfortunately, is entirely up to you.

Personally, these conversations have shown me that I want to try to get to a place at the crossroads of body neutrality and radical self-love, where my body is just what it is and my relationship with it is mine alone rather than a byproduct of what society has told me to think about it. That sounds absolutely divine to me, but it might not fit on you! And that’s okay!

So long as no one is hurting themselves or anyone else on their lifelong journey with their flesh vessel, perhaps the best thing we can do for one another is just support them wherever they may find themselves, just as Olivia and Liz have done for one another. We can be there for one another on our bad body days, but we can reaffirm for one another the constant importance of tearing down the anti-fatness of it all.

To help get anyone and everyone find their footing in whichever body perception direction they decide to take, I wanted to end by asking both of my guests:

Emily: Which resources have helped you the most on your journey?

Olivia: Because my journey toward radical self-love is deeply intertwined with my ED recovery, there’s a lot of crossover here.

Your Body is Not an Apology by Sonya Renee Taylor

Maintenance Phase with Aubrey Gordon and Michael Hobbes

”You Just Need to Lose Weight” and 19 other Myths About Fat People by Aubrey Gordon

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat by Aubrey Gordon

“Eight Bites” by Carmen Maria Machado

Empty: A Memoir by Susan Burton

Act One of “Secrets” and Act One of “The Thing I’m Getting Over,” both stories from This American Life

Emily: Which individuals have had the greatest impact on your relationship with your body?

Liz:

Olivia Milloway—She has put in SO much work to love and take care of herself that it’s infectious. The conversations that we have had together have pushed me and lifted me up more than I can even express. I am so thankful for have her in my life! Everyone needs an Olivia.

Jessamyn Stanley—A professional yogi who preaches radical self-acceptance and accessible yoga for every single body. Watching her do yoga and Olympic-level amazing things has been so liberating.

Aubrey Gordon—My guiding light and true social science queen! Maintenance Phase has been instrumental to me learning about anti-fat bias!

Thank you so much to Olivia for reaching out with this brilliant conversation extension, and to Liz for being game to talk with me now three different times!!! Stay tuned for Olivia’s upcoming Panama-based solo chat and Liz’s inevitable fourth installment.

“And, to this day, Aerie has never carried plus sizes. You can only be #AerieReal if you’re not that fat.”

“As a general rule of thumb, anti-blackness and capitalism are ALWAYS in the room with us.”

The controversy of the term largely comes from the removal of the word fat despite the body type’s adjacency to fatness, making it seem like another vestige of anti-fat bias and prefer the term small-fat instead. As someone who is in a solidly mid-sized body and does not want to either perpetuate anti-fat biases or take away space from individuals reclaiming the word fat, I feel particularly comfortable with the term mid-sized as it allows me to feel acknowledged without stepping on anyone’s toes or taking away from anyone’s experience. Johnston and I have different approaches to the same point, which is: “As a mid-size by definition (but not identity) I feel deeply unsure anything is gained by me claiming I’m ‘fat, a little.’”

“Shoutout to Sister Mary Joseph. Emily is this the first nun shoutout on E4P??” (A quick review of the archive proves that it is.)