Girl, Put Your Mortarboard On

This club has everything: higher education, a round of f*ck marry kill, a brief history of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971

Listen, this newsletter has barely been in existence for a singular year and I’ve already referenced my thesis more times than any of us have genuinely cared to hear about.

A very crazy thing happens when you commit yourself to an academic pursuit which is that you often go very crazy. I did research for like, maybe two years (not acknowledging comments from anyone about how I have yet to shut up about R*y C*hn), and still feel such a sense of pride in and excitement over my work.

I know I’m going to get a text from my mom about how I’m belittling myself but my thesis is truly small potatoes compared to people who are actively choosing to go back to school, especially during a pandemic, to keep pursuing their passions.

I’m genuinely in awe of those who have this drive (and the stamina!!!!) to continue getting higher degrees, and today’s guest is essentially a scholarly marathon runner. This week, I talked with Breylan Martin about her extensive academic journey (she’s working on degrees #4 and #5 right now), the research she’s currently conducting, and which of her three schools she would fuck, marry, and kill… aka the importance of representation in academia.

Hi, my name is Breylan, and my Tlingit name is Náajeyistláa. I am from the Raven-T’akdeintaan Clan and my family comes from Hoonah and Tenakee, Alaska. I grew up in rural north Idaho before moving to Atlanta for college. I went to Emory for my undergrad and graduated last year from Brown with my master’s.

I am currently attending Berkeley while pursuing my PhD in Ethnic Studies. I, maybe obviously, am passionate about learning and am a big nerd– my family is quick to point out that though I have book smarts, I lack street smarts. I may not be super hip or cool but I have great recs for your book club!1

The Girls Who Get It, Get Their Degrees

You’ve heard about Gen Z and student loans. You’ve heard about Gen Z and the workforce. But have you ever heard of Gen Z going to graduate school????

Only a small amount of research has been done on Gen Zs pursuing postsecondary degrees with the best data coming from a National Society of High School Scholars survey2 conducted in a 2020 study (before the pandemic) which found that Gen Z’s “plans to attend graduate school have fallen sharply to 62%, down from 76% in 2018 and around 80% in 2014 and 2016.”

This would make sense, as we learned that there are indications that leading-edge members of Gen Z are entering the workforce at a fairly high rate. A report in the Havard Business Review took this to mean that

Gen Z wants to get its foot on the first rung of a career ladder —a good first job quickly, and without incurring any debt— before deciding what secondary or tertiary postsecondary education pathways to follow… The goal isn’t less postsecondary education per capita. That wouldn’t make sense in today’s global knowledge economy. Rather, the goal is to restage how that education is consumed, from all you can eat in one sitting, to what you need, when you need it.

Essentially, this all makes Breylan’s experience increasingly rare. I asked her:

Emily: Can you give an overview of each step in your academic history?

Breylan: My mom was a first-generation college graduate and I am the first person on my dad’s side of the family to graduate from college. My sister and I didn’t have a family with a background that could prepare us for what college looks like. Looking back at even the process of applying for college, we were so confused and knew so little of the higher education system.

Our applications were to any college that admitted students on a need-blind basis and covered 100% of financial need, though 100% has different interpretations, it seems. My sister and I both went to the place that gave us the most money— so that’s how I ended up across the country at Emory University.

The summer before my senior year I had the opportunity to intern at the culturally focused non-profit attached to my Native corporation, Sealaska Heritage Institute, where I worked in their Culture and History department, specifically in their archives and collections. Learning how to care for objects and papers was so fulfilling, not only because I really love organizing and cleaning, but also because I was learning how to take care of my culture. The incredible information attached to every item there gave me lessons on my history: I remember in the first week of work coming across an ethnography that described my great-grandfather and his fishing boat. It’s no wonder I was hooked and immediately decided to start applications to Museum Studies master’s programs.

I committed to Brown University because I ended up receiving a fellowship that would give me a living stipend in addition to covering tuition. I was in a really fortunate situation being able to attend a master’s program this way which was possible because of fellowships specifically intended to attract those who were previously excluded from the university: people of color.

I enjoy being in a position where I am being paid to pursue my Indigenous interests that ultimately contradict that of the University. Because Brown has open curriculum opportunities, I was able to take some courses outside of the ones focused on application and practice inside my department. I quickly realized that I actually wanted to go to school for longer.

This realization came because of the type of courses I was in. Not only was I able to take courses by Indigenous professors alongside Indigenous students, but also was shown the effect of when Indigenous people and scholarship are taken seriously as reflected in the syllabi of other courses. Indigenous life-ways in and of themselves are ecologically valuable because of their ability to interact with land for thousands of years without the type of destruction seen in just a few hundred years with settler-colonialism on this continent.

I want to academically pursue a deeper investigation into Tlingit life-ways because I believe in the scale-ability of their application. I understand it is odd to pursue this within a university as education has historically been a means of assimilating Indigenous peoples— my own grandparents were taken away to boarding schools as children for this very reason. However, Indigenous people have existed within and around institutions attempting our erasure since the onset of colonization. I similarly hope to re-tool from within, potentially breaking some colonial things as I go.

This re-configuration of what education can do for Indigenous people is part of the reason why I choose to apply to PhD programs. Applying during Covid-19 sucked, and I am so glad I ended up getting accepted to an interdisciplinary program. During this application process, I was surrounded by current Indigenous PhD students, other students who were applying to programs, and a Native professor who helped us out through stress and tears. Going from Emory, where Indigenous people do not have a presence on campus in the student body or faculty, to Brown was academically invigorating and powerful in the ways in which this type of environment helped me grow. (What the hell is up, Emory???)

Now at University of California, Berkeley, it is so fun to me that I don’t even know all the Indigenous graduate student's names; my advisor is Alaska Native, and she isn’t even the only Indigenous person on faculty! I don’t mean to say that any institution has it right when it comes to their interactions with Indigenous people; what I do mean is education is powerful in the West, and Indigenous people are using it in powerful ways and gaining more footing. I, too, hope to use it in meaningful ways.

Because I’m the least mature person in this conversation, I had to ask:

Emily: Fuck marry kill your institutions.

Breylan: I have to fuck Brown, not because it’s particularly fuckable but because I have to kill Emory. The complete lack of presence and support for Indigenous students and faculty is unacceptable. Their non-existent relationship with the Muscogee —whose land they occupy— is similarly disgusting (however, the surface level relationship possessed by my other two institutions isn't it either).

It makes sense that I’m marrying Berkeley, given that I’m going to be here for 6+ years.

Pivoting to whichever the more professional side of my brain is, it’s important to note the relationship that has existed in the US between education and Native populations. Breylan mentioned how boarding schools were used as tools for forcing Indigenous peoples to assimilate into white society, notably not by teaching everyone the Billy the Goat song on the recorder— the motto for one of the largest boarding schools was literally “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues lists the top issue of concern for Indigenous education is how a “lack of respect and resources cause critical education gap.”

Too often, education systems do not respect indigenous peoples’ diverse cultures. There are too few teachers who speak their languages and their schools often lack basic materials. Educational materials that provide accurate and fair information on indigenous peoples and their ways of life are particularly rare. Despite the numerous international instruments that proclaim universal rights to education, indigenous peoples do not fully enjoy these rights, and an education gap between indigenous peoples and the rest of the population remains critical, worldwide.

What Breylan neglected to mention was that what she is doing —actively subverting a space originally designed to intentionally neglect you— is, as they always say in academia, fucking badass. But as actual-girlboss as Breylan’s specific journey is, change can’t be exacted alone. Throughout our conversation, the threads that kept popping out were where and when Indigenous representation appeared throughout her education and how that impacted what she took away from her studies. I asked:

Emily: This is such an obvious question but what are the benefits of proper representation (as opposed to tokenism) in academic spheres? What has your experience been like working with Native professors and scholars?

Breylan: Academic spheres are tools that this settler-colonial nation-state uses to wield its power: universities train the workforce, and influence future leaders who will continue to validate them as institutions that gatekeep privilege. Universities and what they create —technology, science, understanding, and knowledge— have historically created more tools used for oppression of those who adhere to different technologies, sciences, and understandings.

The ‘other’s’ presence alone in the university endangers these goals of the university. Representation’s power in the university is palpable in the types of scholarship that are created, the type of education that follows, and the tangible change this process begets. I don’t mean to say that scholarship alone is socially transformative, but it can be useful as a tool in the plight of building different ways of being through colonial existence.

Encountering other Natives in my education has been very comforting. There are commonalities we share, like not seeing our histories in education growing up, feeling the weight of not wanting to perpetuate invisibility— being moved to correct a classmate or having to ask a professor to please include something else into their syllabi.

I have learned from the fierce and firm presence of Indigenous students and scholars and have found types of belonging vastly different from that in other classrooms. I’m very excited to be able to continue this type of learning at Berkeley, especially for the opportunity for this type of learning while I fine-tune my interests for my research.

Live Laugh Libs <3

If you ever get the chance to ask someone to describe their research to you, I say take it (unless they’re studying something stupid, boring, or harmful in which case you should simply just run away, I guess). Chances are, if the person you’re talking to doesn’t suck, they get really excited and you walk away with more knowledge and a better mood.

Sooo:

Emily: Unabashedly hype up your research in 5 sentences or less.

Breylan: I hope to continue to integrate historical analyses of legislation and other settler encroachments that have impacted the Tlingit, among other Southeast Alaska Natives; I will specifically focus on how Tlingit have carved out spaces of sovereignty and refusal through the enduring presence of settler-colonialism. I hope to also immerse myself in how the Tlingit have used their sovereignty to carry on environmentally conscious resource management under the capitalist system.

Though adaptation to the Western system has caused mismanagement among Alaska Native governance systems (ANCSA Regional Corporations), I hope to argue that tradition infuses modes of survivance with the co-survivance of our environment. I also plan on focusing on how tradition can infuse other areas of modern Tlingit life; one way is looking at the cultural products that come from the land.

With my dissertation, I will specifically connect environmental policy to cultural patrimony using the Tlingit definition as their connection can expand the Western preference of siloed meanings, essentially finding the balance that furthers protection of land, water, and resources in addition to the continuation of Native culture.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, or ANCSA, is the largest land claims settlement in U.S. history. It’s a complex agreement that states that “Alaska Native people had a claim to ownership of all land in Alaska, surface and sub-surface, based on their aboriginal use and occupancy of it.” However, the decided lands and payments are divided amongst corporations (yes, like how the word is always defined), which has made Alaska Natives shareholders of their aboriginal land.

The act was a result of some light loopholing (and I am minimizing the complexity of the history behind this so much right now): when Alaska became a state in 1959, there was an agreement in the Alaska Statehood Act that

any existing Alaska Native land claims would be unaffected by statehood and held in status quo. Yet while section 4 of the act preserved Native land claims until later settlement, section 6 allowed for the state government to claim lands deemed vacant. Section 6 granted the state of Alaska the right to select lands then in the hands of the federal government, with the exception of Native territory. As a result, nearly 104.5 million acres (423,000 km2) from the public domain would eventually be transferred to the state. The state government also attempted to acquire lands under section 6 of the Statehood Act that were subject to Native claims under section 4, and that were currently occupied and used by Alaska Natives.

Because of course they did.

But this is Breylan’s research so I asked her:

Emily: What is different about the legal status of Alaska Natives versus that of Native groups in other areas of the country?

Breylan: ANCSA represents an act of settler colonialism that asserts itself for Western capitalist gain while simultaneously diminishing the viability of Native economy, culture, and livelihood. Though many saw ANCSA as a triumph in terms of land ownership and financial settlement in comparison to the Reservation system, it does not negate the volatile assault on the rights of Alaska Natives —and all Native Americans— to their land, water, and resources.

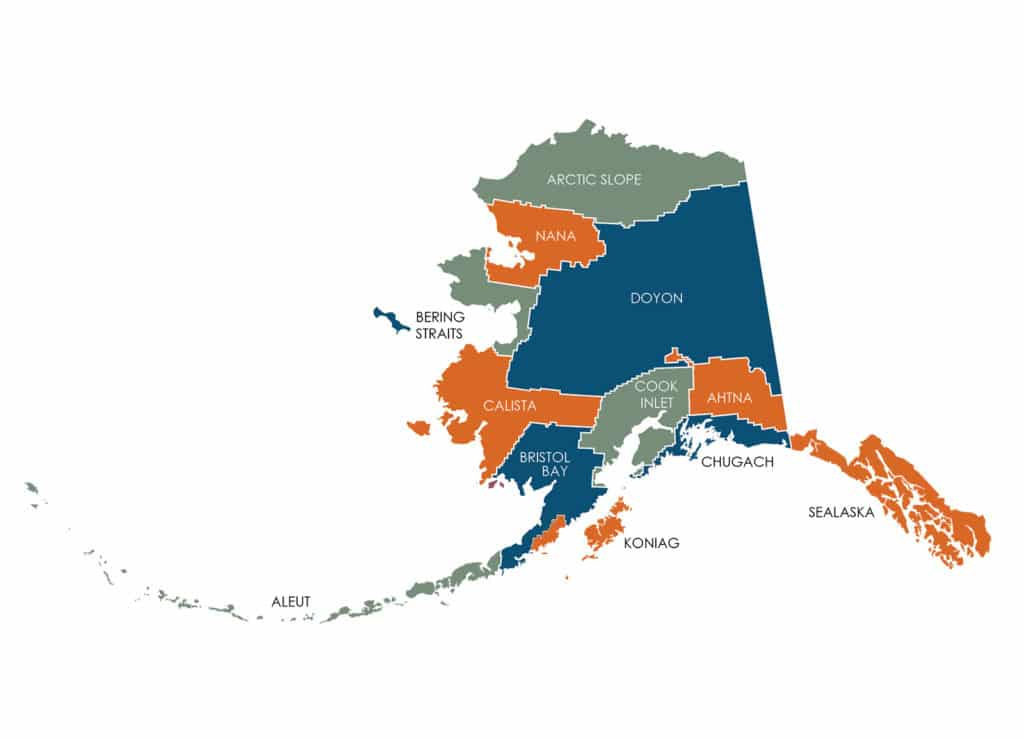

ANCSA “created” 200 village corporations as well as 13 regional corporations that subdivided Alaskan Natives into groups based on their geography. These corporations settled for 43.7 million acres coupled with $962.5 million dollars distributed annually by name of the Alaska Native Fund until 1982, where the funds would run out. The land represents around 10% of Alaskan Native’s homeland, albeit distributed unevenly amongst corporations.

Emily: What is Sealaska and how has it shaped first, the relationship between Alaska Natives and their land, and second, your research?

Breylan: Sealaska Corporation, the regional corporation designated to serve the Southeast part of Alaska along with its predominantly Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian residents, originally enrolled 15,782 members who are often identified as original enrollees which at the time represented about 21% of all Alaskan Natives who met the qualifications the United States presented for being identified as ‘Native.’ We are a massive presence in Alaska! Currently, Sealaska has over 22,000 Shareholders and maintains sovereignty over 1.6% of original Tlingit and Haida lands.

My past research has mostly been on Sealaska Corporation where I have contended that a corporation does not have to be a Western entity and furthermore that regional corporations, such as Sealaska, present a unique Indigenous model that can improve capitalism. I believe that the different forms of sovereignty presented by regional Native corporations prove Indigenous models are valuable guides to future land management and co-management.

(Though I don’t believe in capitalism and would rather have people just give Indigenous people their fucking land back, finding ways around from within is an important means of survival in an adverse world.)

The Future?? I Hardly Even Know Her!!!

The amazing thing about research is that no matter how focused it is on the past, there is always some relevance for it as we move forward in time. Why else would it be conducted in the first place— for fun???

The relevance of Breylan’s research is incredibly apparent, both in its focus and the fact that it’s being done at all. So, of course, I asked the most pressing question:

Emily: What moves someone to get a PhD, besides the chance to return to a twin bed near a frat house?

Breylan: After I graduated from undergrad, I swore to myself that I would never sleep on a twin bed again, thinking I was all grown up. But because I got admitted to Berkeley during Covid-19, I wasn’t able to tour the campus and committed sight unseen— and chose to live on campus for this first year.

It isn’t the best motivation when I’m trying to read that the pong games across the street are accompanied by bad music. But I worked very hard to have the job description of reading and thinking deeply about that material because that alone is massively fulfilling for me, I am only more excited for the next stage of spending deep time exploring my own research question. Time is a huge commodity in this economy, I am grateful for the opportunity to devote so much of it to the length of a PhD.

Emily: After 12 years of higher education, what's going to be your next step?

Breylan: Ahh yeah— I will be 30 when I graduate!! Right now, I hope to continue on in higher education working as a professor and further my research. One of the things that I look forward to is the flexibility a PhD will give me because I see myself in many places working in many different capacities.

But undertaking an educational journey of this size is nothing to sneeze at. Not to mention that it is possible to count the number of Alaska Natives who have received PhDs on twelve hands. (Get it? Because there’s less than 60!!!) I would be remiss not to highlight the significance of Breylan’s work past the length of her plastic-covered twin bed:

Emily: What do you hope your research accomplishes on a large scale? What do you hope your research accomplishes for yourself?

Breylan: That’s a big question!

It’s intimidating to think of the impact of any type of scholarship, but I do have high hopes for myself. Part of my work is oriented towards thinking about the complexity of the relationship Tlingit people have with the U.S. empire while working around its various impositions that are driving our world into climate disaster. I believe these lessons are scalable but also essential for our mutual survival.

On a personal level, scholarship has served me in deepening my connection to and understanding of my culture and history. I hope to use scholarship to make cultural connection more accessible through the very colonial appendages that have historically sought its demise.

Emily: What are you most proud of yourself for achieving?

Breylan: I am most proud of being in a PhD program. I feel so honored that my department decided that my ideas are cool enough to fund me to spend deep time coming up with more questions and attempting to answer them. I remember when I told my grandpa I was headed to Brown for my master’s, he replied, “Okay, after that you’ll go to Stanford Law so you can go get our stuff back from Russia.”

There is so much work to be done and that can be started on with the time I’ve been given here. I may not be going to Stanford Law, but I am working like so many other Indigenous folx for my people and our land— for our future and survival.

Thank you so much to Breylan for being brilliant and passionate and willing to answer my silly little questions!!! I’m so grateful to have an excuse to talk to people doing really cool things in the world!!

Read more about ANCSA here!!

Have to spotlight the fact that Breylan is also completing a master’s at Berkeley en route to her PhD. For those keeping score at home, that’s GED, BA, MA, MA, and PhD. LIKE!!!!!!!!!

Someone once told me this group was like an educational pyramid scheme and for some reason, I’ve never forgotten that. I’ve forgotten who told me and why but, as always, MLMs are forever.