There are a billion and two developing stories we can talk about today—from the horrific and homophobic mass shooting in Colorado Springs to all of the news coming out of the World Cup in Qatar to whatever the fuck is happening over at Elon Musk’s Home for Men Who Are Going to Make Their Personal Insecurities Everyone’s Problem—but as we head into a notoriously rough season for those of us who grapple with our body image, the timing felt right to dive into this particular conversation.

It feels a little “yeah, duh” to say that the beauty standard set for anyone who identifies as female is unrealistic for the majority of us. And even those who fit the mold for what makes a beautiful woman in this day and age will either find themselves uncomfortable in their skin in some way or still in pursuit of looking even better. It seems beauty is not really a destination that can be reached because just when you get there, the expectations have shifted yet again.

And then what about the rest of us, the women who have yet to even hit the glass ceiling of these unattainable standards? How are we ever expected to feel comfortable in our own skin when those who we seek to emulate aren’t necessarily okay in theirs either?

There are so many different elements that make up this conversation, from the presence of racism, fatphobia, and essentially every other bias in how beauty standards are “determined” to why we all care so much about being perceived as beautiful at all. While we definitely can’t cover all of the bases here today, I still wanted to start unpacking these invisible pressures.

This week, Blair Baker returns for her hat trick installment to talk about the sneakiness of modern beauty messaging, ways we can find solidarity in this struggle with other women, and how (or even if) we can ever start to feel better about ourselves.

Despite writing every day for her job, Blair doesn't know how to start this bio. Here are some key facts: 1.) She is obsessed with her dog, Roo. Obsessed. 2.) Her biggest pride in life is her food spreadsheet where she keeps track of every restaurant she has eaten at and wants to with ratings, location, price range, etc… 3.) She is currently at book 46 of her 50 book goal for the year (this is a brag). 4.) Dinner at 6pm > dinner at 8pm. 5.) Her Achilles heel is her Instagram ads…her apartment is furnished by these targeted ads.

Blair’s note: I am speaking purely from my personal experience. As such, I am coming from the perspective of a white, cisgender female, in a straight-sized body. There is a full array of intersectional experiences that I do not feel I have the right to speak on, as I have not experienced them. I keep these experiences in my mind, while not speaking for them. I also want to note I am just brushing the surface of this topic and there is so much more that needs to be covered.

This Body? She’s Keeping Score.

There is both nothing new and endlessly more things to say about women’s bodies and how we exist in them. The same conversations keep expanding and adding more voices, but we are still having the same experiences as all of the women before us. This is both a heartening and horrifying realization: it presents us an opportunity to connect with others and compare notes, while also serving as a reminder that we will never escape the hellscape we find ourselves in.

In the past ten years, the number one beauty standard to achieve has been to have a sunny disposition every time you look in the mirror. The body positivity movement promotes “the acceptance of all bodies, regardless of size, shape, skin tone, gender, and physical abilities, while challenging present-day beauty standards as an undesirable social construct. Proponents focus on the appreciation of the functionality and health of the human body, instead of its physiological appearance.”

There are so many things I can say in response to this, but Blair took the words right out of my mouth:

Emily: What is your current relationship with or interpretation of the body positivity movement?

Blair: Body positivity is an interesting term that has been exploding everywhere. I think the intentions are very positive: they are to tell women who have been taught to think negatively about their bodies for generations to, instead, love them.

The intentions are great, but there are a few issues with it.

1) How are we expected to suddenly feel amazing? I don’t care how many times I hear, “Everybody is a bikini body,” it doesn’t erase history.

2) Body positivity, especially for women, is asking us to stay within the confines of a culture that sees women, and their entire worth in their body (ie. the male gaze). The shift from, “you need to look this way” to “love the way you look” still puts so much weight on how you look.

Right now, I am in a place where my goal is body neutrality, which is seeing your body as just the vehicle in which you move about the world, and the least interesting thing about you. From there, I think you can love your body and the skin you’re in from the perspective of it not being core to your value.

In contrast with body positivity, body neutrality, according to psychologist Dr. Susan Albers, “‘is a middle-of-the-road approach between body positivity and body negativity… As the term suggests, it is neither loving nor hating your body. It’s based on the notions of acceptance and having respect for one’s body rather than love.’” The new movement arose in 2015, almost immediately after the 2012 boom of body positivity messaging, and sought to include those the positivity movement maligned:

While its overall intention was good, the body positivity movement has gained some criticism over the years. Some have pointed out that the movement often leaves people of color, people living with disabilities and the LGBTQIA+ community out of the conversation. These groups were very instrumental in helping the fat acceptance and fat liberation movements gain momentum.

Another criticism is that body positivity can be very unrealistic at times.

“Body positivity is a subset of toxic positivity,” notes Dr. Albers. “Some feel that it blames people for how they feel based on their mindset. It can also push people into trying to feel something that they don’t…Body positivity wouldn’t even be needed if we appreciated and found all bodies inherently beautiful. Society is reflective of what our culture and environments teach us to believe—to dislike our bodies for so many reasons” (X).

Growing up in the 2000s and 2010s, there was never any shortage of commentary on women’s bodies in particular—and there still isn’t today. Thinking about this and Dr. Albers’ comment about how our culture teaches us what to believe about bodies and beauty, I asked Blair:

Emily: How have society's beauty standards and the messaging directed at girls and women shifted in your lifetime?

Blair: If you look at the early 2000s, Heroin Chic was very in trend and all magazines were plastered with “How to Shed 20 Pounds” and were super obvious about including so many fad diets. This rhetoric still exists, but is more subtle in many ways.

I think a lot of it is due to differing beauty standards which in the 2010s valued curves, hourglass bodies, and Kardashian-eque figures. Now, there are definitely more normal bodied women in the media, people speaking out about toxic messaging, and brands now featuring diverse bodies in their ads, but there is always more room to grow.

Long story short: they have shifted to a more “natural” physique when compared to the 1990s and 2000s, but a wolf in sheep’s clothing is still a wolf.

Emily: What role has technology played in the shifting of beauty standard messaging? Do you see technology as a tool of liberation or entrapment for women?

Blair: Technology has been positive and negative. It has opened people’s access to pressures and standards more than ever before—now, you’re not just presented with standards whenever you’re exposed to magazines or media but every time you open your phone or computer. We are forced to constantly be thinking about what we look like.

On the flip side, it has allowed positive messaging to spread to those that in the past wouldn’t have had access. As a person who grew up in a very small town in Idaho, I am still able to see people that look outside the thin, white norm of my hometown.

One thing technology has offered us is the joint Emily Ratajkowski-aissance and Julia Fox-aissance. Here are two women who fit into the most rigid of beauty standards: they are both tall without threatening men’s height envy, thin but still curvy with traditionally feminine breasts and hips, white, cisgender, and have fantastic hair. Both have talked about playing the patriarchy’s game to achieve their positions of privilege and power and now, they both constantly talk about how to tear the whole thing down.

But ultimately, what are they doing?

Don’t get me wrong: I deeply admire each of them and agree with Julia’s comments about aging and Emily’s musings on bodily autonomy. I think they are brilliant women who are using their platforms to elevate important conversations and by no means do I think they should stop because the issue is not Julia, Emily, or other women who look like them: it is that the voices of those who do not fit the beauty ideal are not being amplified to the same degree.

I asked Blair:

Emily: What do you make of conventionally attractive women like Julia Fox and Emily Ratajkowski using their platforms to speak out against beauty standards and the patriarchy?

Blair: This is a tricky one….And I don’t have a straight answer.

I think it’s great when anyone speaks out against beauty standards and the patriarchy—our voices need to be heard. With that being said, it’s difficult when the people who are being the most impacted aren’t being heard.

Is it better for the message to get out regardless of the medium? A lot of the voices of women that are not conventionally in the beauty standard don’t have a platform or wouldn’t be listened to but when its women who are inside those standards, is it null?

Emily: To you, what does solidarity amongst women on the issue of beauty and the beauty standard look like and why is it essential?

Blair: Accepting any and all women in their own body journey; not judging women for how they chose to dress, act, or modify their body. The patriarchy taught us to compare and be competitive between ourselves and this process re-ifys our subordinated position in society, making us feel constantly worse about ourselves. Easier said than done.

Surely we can’t put the onerous entirely on conventionally attractive women to solve the problems they too suffer from, nor should we invalidate their relationships with their bodies just because their experience with societal expectations is “easier.” Thinking like this only serves to further separate us from the common enemies that Emily and Julia constantly highlight in their content: the patriarchy and capitalism.

And yeah, we’re having this conversation again.

It’s You, Hi! You’re the Problem, It’s You

Listen, no one wants to keep talking about men and money less than I do but they just continue to be the root of a lot of the problems we’re trying to unpack these days. Maybe you shouldn’t have built a society rooted in your ego and for your profit—I don’t know what to tell you, gents!

Regardless, women never win when we constantly feel like we’re in competition with one another because:

Emily: Who wins when women feel bad about themselves and their bodies?

Blair: Men!! Who’s surprised? But also beauty companies, plastic surgeons, clothing companies, diet companies, etc…

Emily: What role does capitalism play in the beauty standard?

Blair: Capitalism feeds off of beauty standards. Capitalism is telling you that you need to purchase x, y or z to be a better member of society. In a lot of cases, especially when looking to purchase fashion or beauty products, this is specifically linked to a consumer’s want to fit the beauty standard: the messaging to sell an eye cream isn’t actually “you need this eye cream,” the messaging is, “your under eyes are a problem, but look how much better your life would be if your under eyes were smooth.”

We’re never going to be told we’re enough because then companies would no longer be able to profit off of us. They’d have no need to sell us their goods and services. But we’re enough after we use their products after we’ve squeezed ourselves so tightly trying to fit into an ideal that, in all honesty, actually fits no one.

But why are we trying to fit this beauty standard in the first place?

A viral TikTok is going around right now of a woman unpacking the psychology of conservative women and the notion that when there is a hierarchy (like there always is with white supremacy, the patriarchy, and capitalism), there are some who are exploited and some who are destined to win. While women are considered property, some women—those who make themselves more attractive and appealing to the highest-ranked male mates—are hot property and are therefore destined to always win.

I asked Blair:

Emily: What does competition to be the most beautiful have to do with the male gaze?

Blair: It feeds right on into it. A lot if not all female beauty standards are based on the male gaze, and we are fighting over who can be the most attractive to men.

Our society was built on a foundation of women’s worth being tied to the men in their life. How much you were worth was either what your father was worth—which was used as a bargaining chip for the man you would be set up to marry—making his worth your new worth. While we would like to believe we’re far away from this history, we really aren’t. Women’s worth is still so tightly tied to the way we are perceived by men.

A subjective view of beauty is decided by wealthy and powerful men. If you don’t believe me, look at old, wealthy, not conventionally attractive men, and look at their partners (ex: Hugh Hefner). This messaging is problematic for men, too, saying their value is in what they have, but for women it’s all about how they look.

In order to further ourselves in society, we are forced to enter this competition in order to succeed.

As Blair mentioned, the history of dowries—“an ancient custom that is already mentioned in some of the earliest writings, and its existence may well predate records of it”—shows us that beauty has always been a currency for women to offer to men: dowries, which are payments made to men by women’s families ostensibly as insurance for the new family she is creating, but are largely considered to be a way for men to make marriage to their daughters advantageous for other men1:

In Babylonia, both bride price [“form of wealth paid by a groom or his family to the woman or the family of the woman he will be married to”] and dowry auctions were practiced. However, bride price almost always became part of the dowry. According to Herodotus [an ancient Greek historian], auctions of maidens were held annually.

The auctions began with the woman the auctioneer considered to be the most beautiful and progressed to the least. It was considered illegal to allow a daughter to be sold outside of the auction method (X).

Women’s objective beauty has always been inherently tied to our success in life, and our success in life has always been inherently tied to our value to men.

The frustrating part, though, is that we’re all now stuck in this loop whether we like it or not: as Skylar Corby said a few months ago, as a lesbian, “even though I don’t really want male attention, that is the currency that I’ve learned to accept as a means of knowing if I’m attractive.” We spend all this time trying to feel attractive—to lose weight, to spend a ton of money on skincare, to change our wardrobe—under the guise of doing it for ourselves…but is it? If we lean into body neutrality, will that save all women from existing for and under the male gaze?

I don’t know if I can answer that because, while body neutrality does sound like the healthiest way to exist in a body, it’s unfortunately not all that practical: we can’t all be Scarlett Johansson in Her, a personality entirely disconnected from their physical form.2 Even if we achieve a neutral relationship with our own bodies, they will always be perceived and therefore evaluated by others—and for those who identify as women, regardless of sexuality, that evaluation is largely either done by men to determine our relevance in their lives or by women to determine whether or not we are competition when being evaluated by men.

I’m also not sure I want to feel neutral about my body—I certainly don’t want to hate it and I don’t want to be pressured to feel positive about it when I’m not, but is wanting to feel good in my body so much to ask?

I asked Blair:

Emily: Do you think we can ever get to a place where the beauty standard is accepting of all bodies?

Blair: I hate to be negative, but I don't really think so. Human nature is to “other,” and it's evolutionary to group ourselves as “us” and “them” for survival. So maybe all body shapes could be accepted, but there would be another thing that is evaluated instead. In a dream world, though, it would be less about one body over another because there will be less value in our bodies as a whole.

This would take a culture overhaul. A lot of feminist rhetoric that says that in order to have a truly equal society, we would need to completely over turn culture and start over and that just doesn’t feel likely.

Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder so any solution proposed is unlikely to have anywhere near a total culture shift. Is that why we’re still here? We can launch body neutrality movements, fat liberation, disability awareness, anti-racism efforts, and inclusivity campaigns, but there will always be someone somewhere with the upper hand clinging to their position at the pinnacle of the hierarchy.

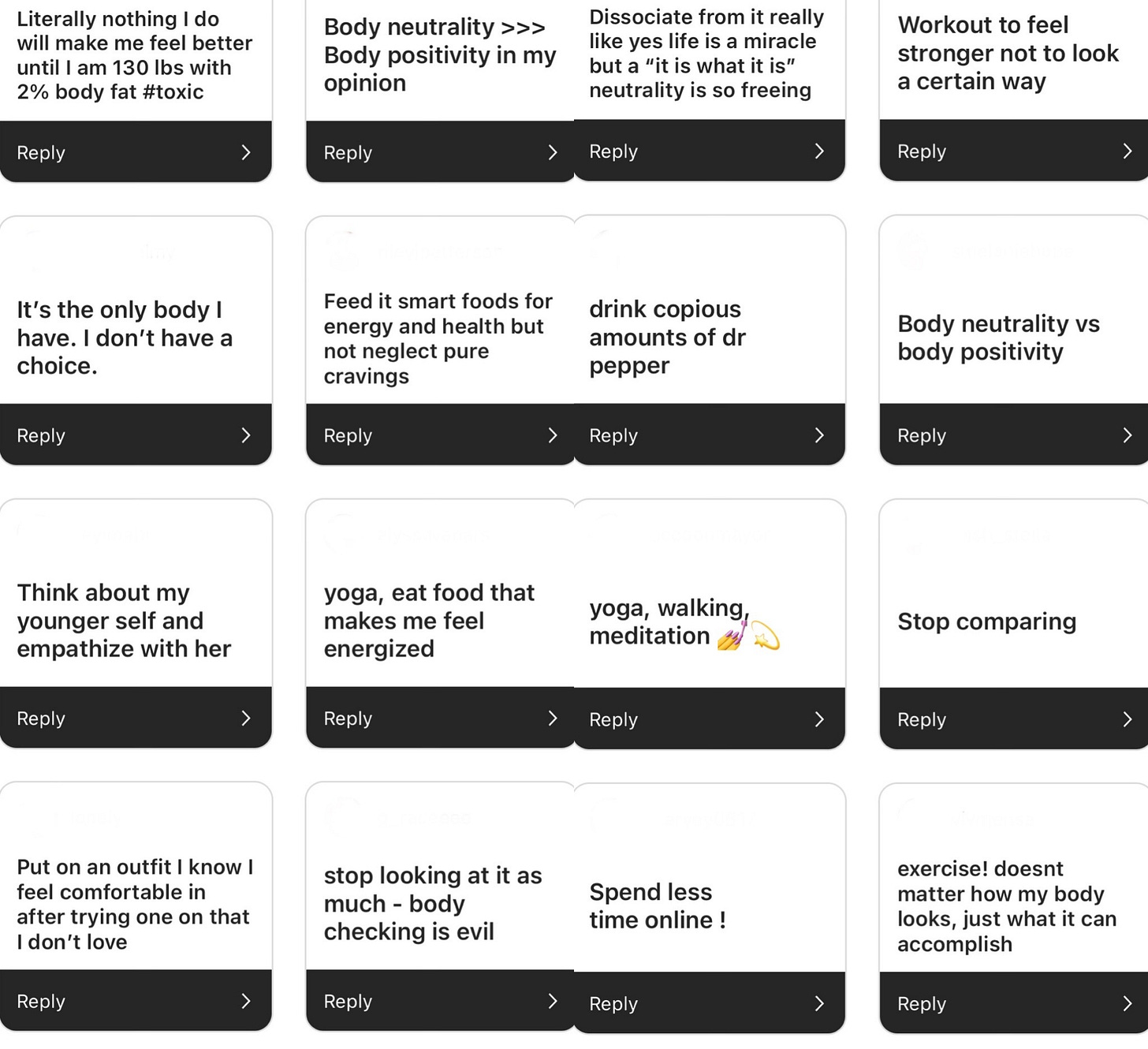

Maybe, then, the best solution is not cultural but internal. We can start by de-centering Western beauty ideals, ignoring weird spin-offs of diet culture, and addressing the internalized fatphobia that seems to be rampant amongst Americans in particular. Then, if you don’t want to feel neutral about your body, find a way to be positive without becoming toxic. If it brings you gender euphoria to alter your body with surgery, do the thing that makes you happy. If you want to cut out all men from your life because they’re still participating in oppressive societal institutions even if they unlearn centuries of implicit behavior, do that!!! Seriously—why should you have to answer to other people’s notions of beauty when it is your body?

No one likes their body every single day—we get sick, we get a bad haircut, we skip a workout (or go too hard during one), we accidentally eat gluten and regret all of the decisions that have brought us to this moment. But if we can find little ways to push back on what the outside world tells us about our physicality—good and bad, in all honesty—and concentrate solely on what makes us feel most like us, then maybe we’ll be so focused on being happy that we won’t need to compare ourselves to one another anymore. We won’t tear down other people’s appearances nor will we need to auction ourselves off for the highest bride price because we’ll be our own best offer.

Perhaps this is a privileged way of thinking from someone who does often skew towards the Julia Fox side of society’s beauty norms—this belief that we can one day fully free ourselves from external pressures—but I’ve spent so many years feeling consistently awful about my body, my appearance, and my desirability. I’ve spent so many years being told I should feel bad and internalizing it, so many years spent being my harshest critic before anyone else could hurt me and I’m fucking done with that.

I want to feel beautiful in the way I find beauty in the world, and in the way Blair does, too:

Emily: How do you define beauty?

Blair: I do get trapped in defining beauty with outward appearance, but when I think about the most beautiful people in my life, I think about their energy. I think about the people who are warm and loving, the people who make me feel warm and fuzzy and bring happiness into my life.

Doesn’t this just sound like a much better way to exist?

Thank you so much to Blair for having this ongoing conversation with me on and offline. She is one of the most beautiful people, inside and out, and I know this because she makes me and everyone she meets feel warm and fuzzy and happy.

It is essential to note that some countries and cultures still have dowries as part of their marital traditions and that this is not a true thing of the past, even outside of its influence on beauty standards.

And even then, her character’s value in the film was largely based on her usefulness to Joaquin Phoenix’s character.

Wohoo!!