Christian Bale's Lost Oscar for "Vice"

While the War on Terror may be over, my fight for justice (a single Best Actor Academy Award) is just beginning

Is there a funny way to talk about the United States’ recent withdrawal from Afghanistan, or the end of the decades-long War on Terror, or the 20th anniversary of 9/11?

Absolutely not. And yet, here we are!!!

What I really wanted for today’s newsletter was to couple two perspectives —one of an American who lived through the terror attacks on September 11, 2001, with another from a non-American point of view— but oddly enough, the US is not very popular overseas. I wonder why.

With all that said, today I wanted to take a look at the recent history of American foreign policy during the War on Terror, how the uncertainty of it resulted in the messiness of our withdrawal from Afghanistan last month, and how 9/11 continues to shape the modern American global identity.

As someone whose conscious memory has largely taken place after 9/11, I wanted to look at the things that have often gone undiscussed in my lifetime. But to create a fair and balanced conversation (suck it, Rupert Murdoch), I also asked my mother —long-time-reader, first-time-guest— Danielle Sharp to answer some questions about her relationship with the War on Terror and how it has shifted over the last 20 years.

There are a lot of moving parts in today’s discussion with a lot of big histories and unknown variables and because of that, there’s only so much I can break down to discuss.1 But… I have a feeling we will be successful.

It Was the War on Terror, Not the War on Comedy

Emily: Name something in your life that did not last as long as the War on Terror.

Danielle: My hair color.

To quote a wise woman: What the Hell Am I Looking At and How Did I Get Here?

A lot seems to be happening at once, all converging around the upcoming anniversary of 9/11: we have the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan signifying the end of a Forever War, coupled with the re-ascension of the Taliban to power in the country and a large population of newly politically active young adults widely condemning every part of the once-favored post-9/11 endeavor.

But how did we get here? Because of the mythologizing of September 11th in American history, what happened on that day has become crystallized in our memories— it’s what followed in the days and weeks where it all begins to get murky.

I asked my mom:

Emily: Can you describe your day on 9/11? Where were you and what happened?

Danielle: It was a beautiful sunny day before the attacks. I was a stay at home parent to you and your brother and pregnant with Audrey. I had a haircut appointment that day, so I had a babysitter scheduled to come watch you guys.

Dad was working in the city and he called me after the first plane hit the first tower. Although he worked in Midtown, he was supposed to go downtown for a conference but thankfully hadn’t left his office yet. As we watched the news unfold before our eyes on TV, I obviously cancelled my hair appointment and, after running to the bank and filling up the car with gas, let the babysitter go home. At some point, I lost contact with your dad until he arrived safely home later that day.

He had gotten one of the last trains out of New York City before it “closed.” I remember seeing the image of a sign outside one of the tunnels saying “New York City is Closed."

Emily: What was it like to be an American in the immediate post-9/11 era?

Danielle: Scary, absolutely fucking scary.

There was the constant fear that we would be attacked again on any given day and that horrible feeling lasted a long time. It effected all of our decisions on a daily basis: “What if I am x when there’s another terrorist attack. Should I not do x because there may be another terrorist attack?”

And it wasn’t just a matter of “planning.” It was a way of living. Or rather, not living.

My mom was not alone: according to a recent Pew Research Center data essay, nearly all Americans who were cognizant on 9/11 felt overwhelming sadness and fear. This led to a bipartisan coalition (gasp— bipartisanship????) where many felt patriotic and “in October 2001, 60% of adults expressed trust in the federal government— a level not reached in the previous three decades, nor approached in the two decades since then” (x).

This trust is how the Bush administration was able to mobilize the military to Afghanistan so quickly. According to our favorite historian,

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, suspicion quickly fell onto al-Qaeda. The United States formally responded by launching the War on Terror and invading Afghanistan to depose the Taliban, which had not complied with U.S. demands to expel al-Qaeda from Afghanistan and extradite al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. Although bin Laden initially denied any involvement, in 2004 he formally claimed responsibility for the attacks. Al-Qaeda and bin Laden cited U.S. support of Israel, the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, and sanctions against Iraq as motives.

The War on Terror is a tricky bastard because it was both a military effort against a very specific target (terror) and a very vague target (terror), and on September 14, 2001, Congress voted to grant President George W. Bush “a broad, open-ended authorization for military force” in Afghanistan, with the House voting 420 to 1, and the Senate voting 98 to 0.

Three things stand out about all of this information: the first is how vulnerable the American people felt after the attack. Not only was this a shocking blow to the American identity (that we were an indomitable force), but it resulted in devastating personal losses for countless people. The second was the number of villains who fit under the “terror” umbrella. And the third was the lone vote against authorization of force.

The combination of all three is how we’ve reached the conceivable here: America immediately invaded Afghanistan to attack a number of enemies with varying degrees of success before expanding outward to exert further military dominance in Iraq with the defense of being to protect the American people and with the support of Congress.

Hindsight is 20/20 (as is the year replaying on loop for everyone in Hell), and this is incredibly clear in the results of an Instagram poll I put up earlier today. As of writing this, 474 people have seen the story —bragging, I know— and 86 of them have responded to the question “Was the War on Terror justified?” Of those 86, only 10 have responded “yes.”

How did we end up in this disaster in the first place? And why has it been such a messy situation to get out of?? And are we the bad guys???

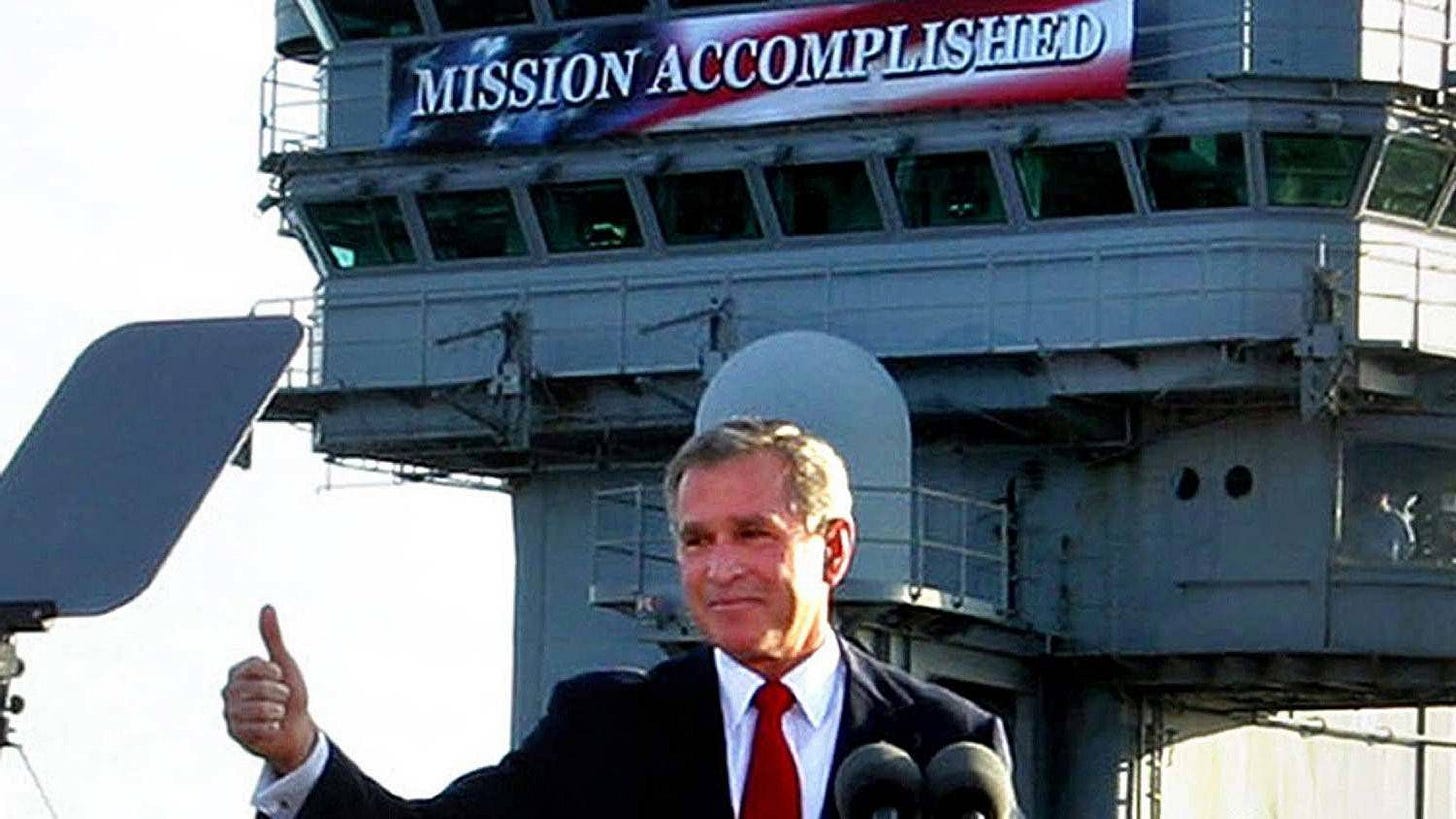

Nothing Says Unsolicited Involvement Like a Dick

The way the War on Terror was conveyed to Americans at the start was that we were just going in to attack our enemies who were the direct perpetrators of 9/11. Just as President Biden said when defending the recent withdrawal from Afghanistan, the objective of the war was not nation-building (or, “the process through which the boundaries of the modern state and those of the national community become congruent”).

However, as journalist Sebastian Junger recently wrote, many Afghans thought that we were going into the country —under the banner of waging war on terror— to also get rid of the Taliban. Junger recounted what it was like to watch Kabul’s liberation in November 2001:

The citizens of Kabul were dancing in the streets and flying kites and carrying radios that blared Indian pop music. A young boy sailed by on a bike playing harmonica, and a man came up and hugged me when he found out I was American. I had always wanted to see a city liberated, and my wish had finally been fulfilled. Not only that, but it was my own country that had done the liberating; I felt a warm infusion of national pride.2

But he follows that moment of hope with this argument:

American efforts in Afghanistan can’t really be compared to the vast imperialist undertakings of the British and the Soviets; if anything, we weren’t imperialist enough. Taliban resistance collapsed almost immediately in 2001, but instead of following through with a massive infusion of troops and relief, the Bush administration moved on to a completely unnecessary war in Iraq.

What, may you ask, is American imperialism? In a 2003 article in Political Science Quarterly, Paul McCartney (not the fun one) wrote that “U.S. foreign policy frequently tries to have it both ways—to assume that America’s national interest and the greater good of mankind are one and the same.” American imperialism can be explained as the idea that American interests are the best interests and we are doing a good thing by enforcing those interests in other countries, even if our interests aren’t in the best interests of those countries.

While elected officials like to deny ever promising nation-building in Afghanistan following the defeat of the Taliban, Junger’s experience reveals that Afghans interpreted imperialism as a good thing, with intervention equaling assistance. And assistance from America might be helpful when a nation is suddenly pivoting from religious military rule to an American-like democracy when the last time Afghanistan was close to that style of government was the brief five-year window when a republic was established from 1973-1978.

As Junger explains:

Afghanistan was initially allotted only about 10,000 American troops—one quarter the size of the New York City police force—and was all but abandoned by the State Department. Even with that small level of support, the Afghan endeavor might have worked had the Bush administration—and then the Obama administration—tackled the one thing that Afghans have always demanded, and that all people deserve: an honest and transparent government. Instead, we essentially stood up a huge criminal cartel that posed as a government.

We wanted Afghanistan to become a democracy for our benefit, but gave them no tools to do so. We entered a country unsolicited and just fucked up their government. For better or worse, imperialism is always invasive and disruptive.

But Emily, what does this have to do with Dick Cheney? You built it all up around him and then left us with nothing— just like the government.

How did we end up resorting to all these wars in the first place? Because of war hawks like those who filled President Bush’s cabinet, largely led by Vice President Dick Cheney, who saw a moment of vulnerability to co-opt and exert dominance— not just as Americans but as individuals, and not just in Afghanistan but wherever they had vested interests.

And how were they able to do this? Remember how I noted those three components before?

First, that it is easy to declare war when it has the support of the American people. As my mom shared:

Emily: What were your initial thoughts on the War on Terror?

Danielle: I am not a big fan of the concept of “war” in general. I understand the excitement of “war games” and the idea of Stratego and all that. The actual act of war is hostile, aggressive, and deadly. What’s good about that? I get that disputes have to be solved somehow but in my opinion and in general, war is not the answer.

Nevertheless, as a living breathing American on September 12, 2001, my initial thoughts on the War on Terror was almost a relief. That is: my country has been attacked beyond imagine, and my government is doing something to protect me and to make sure it doesn’t happen again. I know it sounds somewhat contradictory, but that is how I felt.

And I’ll let you in on a little secret: I did not vote for George W. Bush the first time around, but I did vote for him in 2004 and the sole reason I voted for him was because of the War on Terror.

Next, it is easy to expand the war —like we did by invading Iraq and attacking Saddam Hussein even though we hadn’t succeeded at winning against our original target— when the enemy is as loose as just “terror.”

Emily: Why did you think we kept expanding our reach in the Middle East to include attacking Iraq and going after Saddam Hussein? Was that effort conflated with the invasion of Afghanistan?

Danielle: I think it was a continuation of the “War on Terror.” Did Bush and those in charge of the military use the War on Terror as the entry point as the justification for the invasion— yes. I am not sure why the focus of whether there were actual weapons of mass destruction was necessary to justify invading Iraq.

For me, at least, it was justified because of what felt like the real threat of Saddam Hussein to America.3

Emily: Do you think there was ever a conceivable end to a war declared on "terror" at large rather than on a direct enemy?

Danielle: I think there were probably certain objectives that those in charge thought that if they achieved, then we would have “won.”

I mean, in a speech addressing Congress and the nation on September 20, 2001, President Bush said, “Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.”

But in reality, will every terrorist group ever be fully found, stopped, and defeated?

And finally, no one in Congress questioned any of these military efforts when they granted a sweeping authorization that allowed Bush and his cabinet to do anything in both Afghanistan and Iraq. No one in Congress, minus, of course, Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA).

Okay, So Rep. Lee Might Have Predicted the Future

In all honesty and without condoning anything, I don’t know if there was any alternative reaction to 9/11 besides the War on Terror. I want to believe there could have been— one Rep. Lee suggested that we attempt to seek in 2001 when she said:

“However difficult this vote may be, some of us must urge the use of restraint. Our country is in a state of mourning. Some of us must say, ‘Let’s step back for a moment, let’s just pause, just for a minute, and think through the implications of our actions today, so that this does not spiral out of control.’”

We are so far past the point of being able to conceive of an alternative that we were also unable to ever find a good way to withdraw, largely due to the factors that Junger discussed. Last month, as the Taliban moved into Kabul to secure their takeover of power in Afghanistan, America messily moved in the opposite direction as it tried and failed to safely evacuate US citizens, visa applicants, and refugees.

I asked my mom:

Emily: What are your thoughts on the recent withdrawal from Afghanistan?

Danielle: There was probably never a good time for the withdrawal because once there, our military presence was relied upon. After 20 years, we can’t just slip out in the night and hope that no one notices. Chaos and casualties would have ensued whenever and however it was undertaken.

Amidst the evacuations, a terrorist bombing at the Kabul airport killed 73, plunging an already chaotic situation further into insanity and danger. In response, President Biden claimed we would “get” the people that carried out the attack and launched airstrikes in the region.

The whole situation reminded me of President Bush’s promises after 9/11, as well as the opening invocation at a memorial service on September 14, 2001, that Representative Lee heard which inspired her vote: “‘Let us also pray for divine wisdom as our leaders consider the necessary actions for national security, wisdom of the grace of God, that as we act we not become the evil we deplore.’”

I asked my mom:

Emily: Do you think —in occupying Afghanistan for over 20 years, in our drone strikes and assassinations, and neglect of immigrants and refugees from this region— America has become the terrorist in this situation?

Danielle: We may have done all of those things, but I do not believe we are terrorists. I do not think our actions as a country —however ill-advised or poorly planned or maybe even morally wrong— constitutes terrorism. The definition of a terrorist is a person who uses unlawful violence and intimidation especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political gain.

I do believe there are Americans who are domestic terrorists, but that’s not what this edition of E4P is about.

That brings us to a weird full circle. I’m sure a smarter journalist has already made this connection, but I would be remiss not to mention one sick irony of all this. On 9/11, as Junger writes, “a fourth plane was supposed to take out the Capitol building in Washington and effectively decapitate the U.S. government.”

The ironic part is that some of the people who cling to the deep-set patriotism established after 9/11 were those who stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021, to effectively decapitate the U.S. government. The evil we deplore was inside us the whole time.

Maybe, since we suddenly have some freed-up time, we can spend the next twenty years nation-building on our own soil instead.

The Lowest of High Notes

If there was no good alternative to the War on Terror and no good way to leave Afghanistan, is there anything we can do that is good in the future?

I believe the only way forward is to apply accountability we discussed last week on a far larger scale: why are we so eager to defend our actions instead of recognizing they’re wrong, invasive, and have thus far only failed? If we stopped acting in what a few bland men say is our “best interests” and actually listened to what other nations want from America in the global arena, maybe then we’d have the prowess without inflicting suffering.

It’s a very small fraction of what is owed back to the world and Afghanistan and all the people lost in this on-fire dumpster mess, but it is one way to stop us from thinking with our Dicks when it comes to something as drastic as war ever again.

Emily: Do you still subscribe to the American belief that we the people are inherently good and just?

Danielle: I’d like to believe that.

I don’t know if I do right now, but I agree— I’d like to believe that, too.

Thank you to my mom for being so honest in her responses for this week’s piece!!! There will be no Emily For President next week because I have big plans and even bigger dreams!!!

Also, if you’ve made it this far, I’d like to address the elephant in the room: no, I did not mention Rudy Giuliani in a 9/11-centered piece, which is yes, incredibly off-brand for me. There simply wasn’t enough time or space to share how Rudy just did his job well one time.

I acknowledge this piece neglects a conversation about Islamaphobia, xenophobia, immigration beliefs and rights, and the military-industrial complex.

To be sure, this is just one journalist’s experience.

This is such a weird sidebar and it does not excuse anything Saddam Hussein ever did, but a really fun fact about him is that he actually was given the key to the city of Detroit in 1980.