We Were Writers Together

What if writing sessions were set to the Challengers (2024) score? What then?

Much like Taylor Swift, I’ve been thinking about Matty Healy a lot lately. This is largely because I’ve been trying to explain the Matty Healy of it all to people who did not grow up on Tumblr, but also, if I lie for the sake of this intro, it’s because I’ve always seen him as a functional literary device.

Matty Healy is many things but, above all, that man is a poser. So often, he wants to sell you on something—his music, his art, his persona, his real-life identity being a halfway decent guy despite all of the stuff you’ve read about him—that you don’t even know what you’re buying. When you boil it down, he’s the perfect metaphor for much of today’s discussion: he’s a writer whose presence makes us question how seriously to take him and the work he produces, then question why we need to question that, then question what we’ve done to put us in a position to question anything ever. It’s a loop that is not unfamiliar if you spend any time on X or Goodreads when you have loved or hated a piece of writing.

To be clear: I’m not making a case for Matty Healy—not even 16 out of 31 songs on Joe Alwyn’s breakup album could make a case for Matty Healy. I am, however, taking the longest-winded route to introduce today’s piece on writing and, to some extent, how we talk about it. This week, I spoke with Julianna Chen who writes lover not a writer here on Substack about her writing (which I adore), writing as a woman of a certain age with a certain internet digest, and what even makes someone a writer anyway.

Born in Pittsburgh and now living in Dallas, Julianna Chen is a “writer” (TBD by you, the reader, after this Substack post) and a recovering horse girl. When not circling back and touching base at her day job in PR and corporate communications, she is likely reading fan theories about the movie Challengers (2024) or picking up a new read at her favorite local bookstore.

Friends & Writers

I first reached out to Julianna after she posted excerpts from a recent Substack post on her Instagram stories. Much like how I viewed Sean Jones’ podcast development from afar, I had loved the snippets of stories Julianna would share throughout the years. We had just missed each other in college—she had joined our sorority as COVID booted me out of it—and while I had long thought she possessed the coolest presence, I didn’t want to be a fucking creep and tell her. Hence the lurking!

Julianna’s personal essays had a tone that always struck me as a little familiar, but it was only with her most recent post that I realized how much her writing reminded me of E4P superstar Rebecca Loftin. But it wasn’t just Rebecca’s current work that Julianna reminded me of…

Can I overshare for a minute?

When I was 15, I attended a pre-college creative writing program where I met a version of the woman Rebecca is now. She was bubblegum pop with a bite during the peak Marina and the Diamonds years (another Tumblr reference—keep up) and wrote well beyond her years. Her ability to capture emotions and experiences I was having just the step before I learned how to grapple with them was uncanny, as one of her greatest skills is to write about her life as if were a story we were all a part of.

So you can imagine how endearing and inviting it was for me to read Julianna’s words and feel that same rush of, “Oh yeah…That!” It’s validating in a funny way to connect with someone else’s writing, and I’m so fortunate that I have an excuse to talk to Julianna past just swiping up on her story to say, “Great piece! I loved it!”

Every E4P installment starts with a preliminary chat of a length to be determined by my guest that will help shape the loose outline of the piece. Rarely do these conversations last longer than an hour and a half, and rarer still do I have two such conversations for any singular article. I don’t know what it says to you all that today’s conversation came together over the span of three hours but to me, it says that we had to condense a lot of big ideas into this one little space.

With that, I wanted to start by asking Julianna:

Emily: Dare I ask...why do you write?

Julianna: If you were to ask my parents—who I am about to reference in every question of this interview—they’d maybe trace this back to when I was a year old celebrating my zhuazhou, or “first-birthday grabbing ceremony,” and selected a pen from a tray of objects meant to predict my future.

But, as I recently wrote in a Substack post, I’m not sure that I believe in being “born” to do something and I also don’t know that there’s ever been a reason why I wrote. As a child, all I knew was that I liked to make up stories and as I got older, it became less about what I enjoyed and more about not knowing what else there was.

I don’t mean that in the career sense, either, as if I’d always been told I was good and naturally kept following that path—I work in PR! I don’t write professionally! I just mean that writing seemed…obvious. It’s just always felt as simple as knowing something or hearing something in my head and feeling like I HAD to write it down.

Emily: Where do you draw your inspiration from, and has the source (or sources) changed over the years? And how does your cultural identity inform your writing, both consciously and unconsciously?

Julianna: I really just write about things that happen to me and people that I love. So—breakups. A trip I went on. My parents above all. If I ever wrote a book, it would be about my parents.

It’s funny that I’m writing this now because in the same Substack post I referenced above, I talked about how some of the first things I was ever proud of writing were about being Chinese, and how this worries me now because maybe it means that I’m not a real writer—more on that in a second—since I can ONLY write about being Chinese. But then…my first instinct when I saw this question WASN’T to say “race.”

The thing is, I think when I was sixteen years old, “things that happen” meant writing about racism I’d experienced in the predominantly white town I grew up in because it felt like the biggest thing to happen to me, the only interesting thing that could happen to me. But my world is so much bigger now, and I would like to think that the care I took back then to write about myself and what I went through has deepened and extended outward into this desire to write about my family members who are endlessly interesting, much more so than myself.

Being Chinese is obviously inextricably tied to that, and I think as long as I’m alive and have this richness of background I will always have things to draw from and write about.

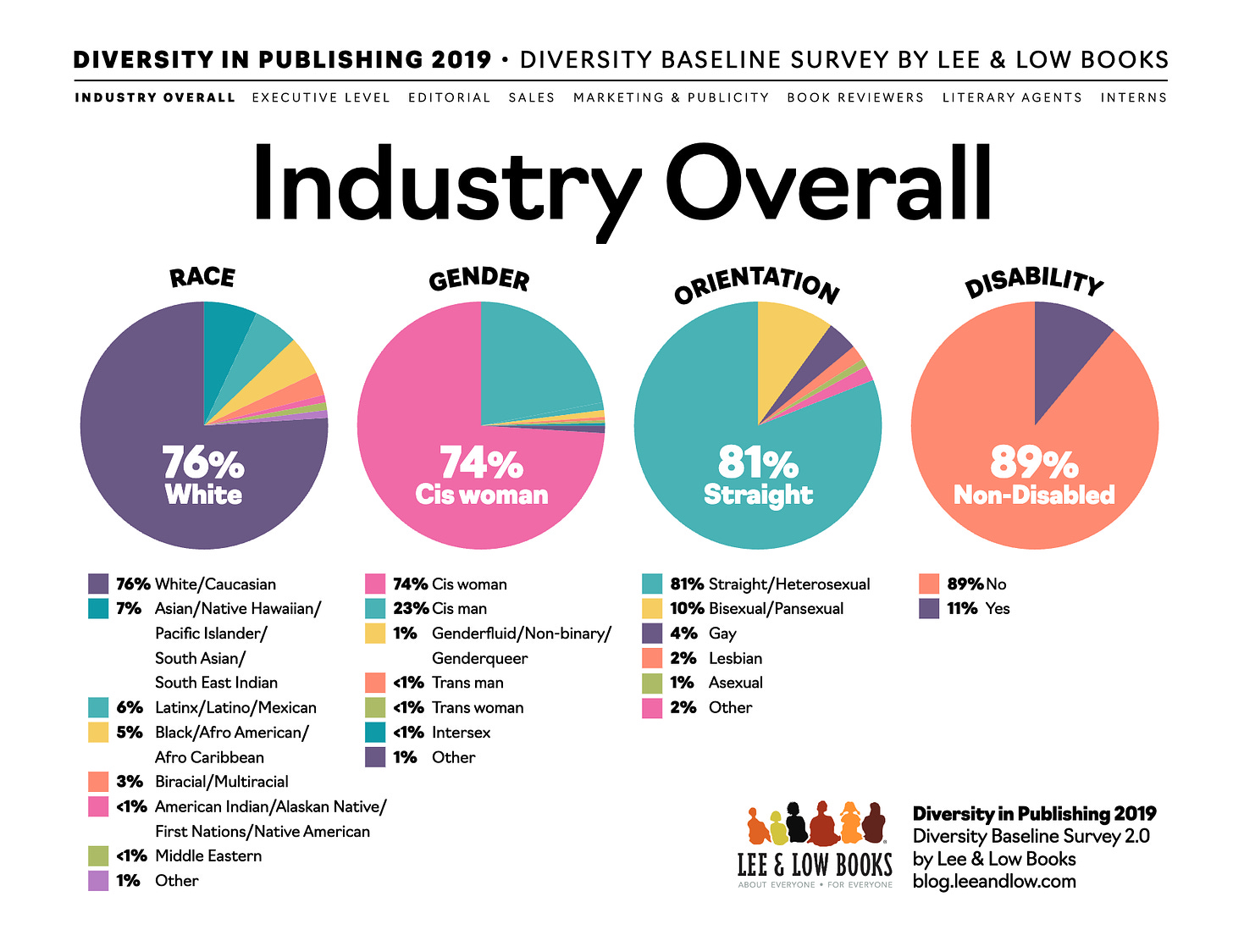

I don’t think I’m telling anyone anything they don’t know when I say that there is no shortage of books written by white women. That’s not a read—I love Dolly Alderton, et al.! But through our conversations and her essays, Julianna has grappled with a thought that I, as an abundantly represented demographic in book publishing, had never had.

The data I could find on Asian American representation in the publishing industry is a bit dated but as of 2019, only 7% of those in the book world were AAPI. That’s a horrifying statistic by any standard, but even crazier when you see it in context:

All of this, coupled with her previous responses, led me to ask Julianna:

Emily: You wrote this really great piece that touches on this fear that "any stories worth telling have been told by MFA grad talents far greater than yourself," particularly when it comes to writing about your life as an Asian American. Can you expand on this idea that someone has already written your stories before you?

Julianna: One of the most incredible feelings you can have while reading is feeling truly, deeply seen, like the author is hanging out in your head, and sometimes I think I’m holding myself back from experiences like that because I know that the books that make me feel truly seen also make me feel sad and angry about the fact that the author has had similar experiences as me but is far more skilled.

My anger is driven by this sense of urgency. I’ll think to myself: let me cook for, like, seven more years and I can get as good as her, but what if there is no appetite for this particular type of story anymore? What if publishers and the general public decide that they have seen enough memoirs about Asian moms? I don’t feel like people around me would ever outwardly express that and say, “Hmm, I read Oh My Mother! by Connie Wang so I think I’ll pass on Unnamed Mother Memoir by Julianna Chen.”

But then I think of all the people I’ve ever heard use AAPI as a genre descriptor (which it is not), use book titles from AAPI authors in reference to each other when it doesn’t make sense. (“For Fans of Crying in H Mart” and then the other books are…happy, but by Korean people?) I do try to tell myself that Asian American experiences are so vast, and even the book that feels most similar to my life is still not exactly the same as my life, but I think I’m trying to balance that against my cynicism that behind the scenes some publishing exec is saying something about having met a quota of “diverse voices” for that year or a “moment” being over.

I share a lot of Asian American memoirs with my mom, and she’ll always say something about how “this stuff” is “popular now.” I know she means that in a good way—but I always wonder whether there’s an implication that one day it won’t be popular.

When I think about what is the most “popular” in this current literary moment, there is one intersectional demographic I fear we have to discuss at length, and that’s hot mysterious women who write hit books.

We’ll Always Have Dimes Square

Maybe the mini Matty Healy think piece in the intro will make a bit more sense as we pivot the conversation over to (and a chill runs down my spine) Literary It Girls.

Listen, I love It Girls—always have, always will. But there’s something about this not-new trend back on the rise of indie sleaze writers with establishment recognition that has me shaking in my sparkly pink cowgirl boots. I fell down a bit of a rabbit hole while writing this, a mental doom scroll of comparison, if you will, and had a number of not-entirely-great discoveries about myself and these new ingenues along the way.

The first taste on the palate when consuming Literary It Girls is confusion. While they do allegedly have a precedent—you’ll often see these women compared to Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, as well as the sceney bloggers of the early aughts—there’s an air about them that screams, This has never been done before!!!! The second flavor is, get this, also confusion: Dwight Garner writes about the sharp observations in Honor Levy’s debut, My First Book, in a way that paints her as a holier-than-thou genius. But then, he states that “what pushes Levy’s stories beyond being merely on the level of smart magazine essays is the empathy you can sense below the starkness of her sentences.”

A similar sentiment is echoed in reviews of Allie Rowbottom’s novel Aesthetica1 which is both a spiky critique of influencer culture’s impact on the beauty industry and a sometimes painful mother-daughter story. These women, like their works, are edgy and cutting, but then just vulnerable enough that you question if the whole thing is just an elaborate façade.

You might be wondering, “Why should I care?” I don’t know if the “you” in question has any reason to, but I share this because if you’re a female writer of a certain age who also spends time on the Internet, these women are always there. And if it sounds like I both love and hate comma fear and revere them, it’s because I do—all at once. They’re phenomenal writers who sometimes show how clearly they know that to be true; they have fantastic author photos and Instagram grids that highlight how little they care about your perception of them; they’re so fucking annoying and so goddamn cool.

But the thing about these It Girls, at least for someone like me who has spent years in life and in therapy growing comfortable with being earnest and genuine in public and online, is that we never really know who they truly are. They’re the women mysterious enough to build omnipresent lore in certain circles—always seen on their way somewhere else, somewhere better—so you’ll never truly know which image is the real person and which is a reflection in a funhouse mirror.

Notably, a trend amongst these trending woman—a trendception, if you will—has been to orchestrate and then host their own book launch parties. In a piece for Nylon earlier this year, journalist Sophia June interviewed a number of Literary It Girls (Rowbottom, Delia Cai, and Marlowe Granados, to name a few) who each said that they took matters into their own hands because they wanted their book celebrations to reflect their personalities, their projects, and their aesthetics. But, as June continued on to explain, the parties double as a clever marketing tactic:

part of what makes someone magnetic is, of course, that we don’t know everything. These literary It Girls toe the line of marketing persona and of keeping things sacred so they can create in the first place.

While Julianna will probably shirk the comparison, she does have this same enviable elusive candor in her writing. I was particularly struck by it in her most recent essay, “talking to god about the texas rangers,” where she wrote about her breakup, her city, and loneliness in a way that a novelist would have their character explain. It’s gut-spilling yet intriguingly distanced in a way that prompted me to ask her to come on E4P immediately after I read it.

Having gone on long enough, I wanted to ask Julianna:

Emily: I'm fascinated by how you write about yourself in your essays—it reads both like you're inside yourself and a character in a story. Have you ever noticed that and, if so, is it intentional?

Julianna: I don’t think I’m doing any of this consciously. The process is: I am living life, maybe hanging out outside, doing my thing. And I’ll see or feel something and the idea will pop into my brain, and the idea is not really a general, overarching idea like “poem about trees” but always a super specific phrase about the trees that everything else will then come from.

When I’m writing about myself, it’s the same thing. The ideas that pop into my head about myself feel like they come from outside my body as if I am two people and one person is making objective observations then piping them into my head. All this to say: I’m not real when I write! Everything that happens to me almost feels fake, as if it isn’t even actually HAPPENING, and then I’m able to write about myself the way that I do.

The cringe example I could give is that my ex-boyfriend and I were at Half Price Books; he always loved Half Price Books and I never did because the sheer size of the Dallas flagship we go to really overwhelmed me, and as we were there I felt like I saw myself from outside of myself, dragging my feet and acting all disgusted by the older, mustier books. The phrases that came to me were about holding books by their corners gingerly and needing all the work to be done for me, needing these glossy hipster-curated indie shops to do that work for me.

I was not a real person or Julianna Chen then. I was just seeing myself like some random character. Nothing ever actually came from that, but it’s just an example of a time when I did something and saw…myself at the same time.

Of course, this then led me to ask:

Emily: What role does self-awareness play in your writing, and do you wish it factored in any other way?

Julianna: Even as I write my answers to these questions, I feel dumb because I’m self-aware of the fact that I’m not a published author and maybe giving an interview where I talk about things like “process” and “inspiration” is a bit self-important. Outside of the world of this interview, though, I think my self-awareness is more like anxiety. Is it being self-aware or being hypercritical—I don’t know.

I’m always telling the friends and family who gas up my writing that it’s too flowery, uses the same “list three things separated by commas” structure (I AM DOING IT RIGHT HERE!), and gets sloppy at the endings so it relies on a little reference to the language used at the beginning of the piece so I can lazily tie it all back up. Everyone tells me that I should be nicer to myself. One of my friends said, basically, “Who cares? And why does it even matter because if it’s good, I don’t really care,” and then I said, “Well, it’s not THAT good,” so we ran in circles. For me, there may be no cure for this besides simply getting better at writing.

And so the thing about writing that is overly self-aware is that it needs to do something about whatever it’s aware of. I wrote once “…admittedly, the term “Asian American experience’ is one that I am still neutral-to-meh about, but…” and it’s like….Okay, so use something different? If you’re going to be self-aware or poking holes in your own writing on the line level, then fix it instead of writing more about it.

In the first essay Julianna published on her Substack, there’s a line that reads: “When your mother comes to visit in July, she agrees that Dallas is so ugly, says that maybe JFK wouldn’t have been hit in the head had there been more trees downtown.” It’s one of those lines that you would think means nothing in the grand scheme of things, but is so convincing and gets at the core argument of the piece—that she thinks hates her new city, and here’s why.

That’s the beauty of Julianna’s writing: it reads so smoothly, like literary ASMR. Just the same, it tells us enough to know what she’s thinking but not enough for it to feel entirely vulnerable. There’s a level of restraint in that essay that I don’t know how to imitate—I’ve literally confessed to wanting to commit grand larceny on this newsletter—so, of course, I had to turn my admiration into a nosy-ass question.

Thinking it might have something to do with our above Dimes Square Writers discourse, I asked:

Emily: How does your relationship with internet culture factor into how much of yourself you're willing to share in your published writing, if at all?

Julianna: I’m extremely, extremely online, and I wouldn’t say that this affects what I share, but it does affect how I view the quality of my stuff. When people tell me they loved my Substack piece, I have this horrible voice in my head thinking, “Of course, YOU thought it was good since you don’t really read a lot, but I bet if I posted this on Twitter every cool, well-read mutual I have would tear this shit apart.”

Two weeks ago, there was major discourse about how Ocean Vuong, of all people, is a bad writer, and I was just like…what’s the point? If this tweet saying Ocean Vuong sucks has 400 retweets and thousands of likes, I might as well just give up before ever trying to write anything and share it online again. The flip side of this is that I am a hater to my core and I sometimes see really horrible shit go viral and I’m just like, again…what’s the point????

I am being dramatic there, but overall I think that the things I read online are so heavy on these buzzwords, these references to the last big author drama or The Cut essay, and I’m always hyper aware of where my writing might figure into that—whether it could be lumped along with the “cringe Dimes Square NY Mag 26-year-old voice of a generation” profile. I’m just thinking of these things that I feel don’t exist to people that actually matter in my life, but then I get online and it’s like…these people DO matter! They’re IMPORTANT!

They’re big journalists or critics; it’s hard to say none of that matters when, objectively, there is good and bad writing, and I know I cannot deliver for these people! I think the solution I’ve found is to stay unbothered because I know that I can’t really run with the cool kids here, and to be realistic about who my audience is—again, my offline parents.

Emily: With that, would you say you write for a specific audience or do you just write for yourself?

Julianna: I just don’t think there is anything at all without an audience! Baby girl, if there is no audience, that is your journal! Your Notes app!

I have to say this to myself here because I’ve been doing this thing recently where I say, “I ONLY write for myself!!! I don’t care what ANYONE thinks, it’s only for ME!!!” which is just simply NOT true and moreso a way of evading criticism or making the criticism I get feel less important. That being said, the people I really care about impressing are basically, like, my parents and other Asians who are obsessed with their parents.

I think audience is a necessary consideration in writing because if your work is not a journal entry and is in fact meant to be read, you should be concerned with whether it flows right or feels good, and you should be reading and rereading what you wrote with other people in mind. I also think this kind of gets back to the question of why I write or why anyone writes—when I think of someone who “writes for themself,” I always imagine someone who says that they write because, like, it’s…therapeutic? And helps them express themself?

Which, no shade if this is something you say, but what I mean to say is that I don’t actually find the act of writing to be enjoyable.

I’ll maybe feel excited about pursuing an idea that pops into my head, fleshing it out more, but I don’t find that the “fun” factor of writing is enough to serve me if there is no audience. It’s not therapeutic until it involves others because the therapy part for me is about the responses, the connection, the “Oh my god, this happened to me too.”

A Writer By Any Other Name Would Still Be a Writer

In an unrequested but incredibly necessary follow-up, I did realize what milestone I needed to hit in order to call myself a writer: I needed to bolster my dating app profiles a little bit because my real job title is definitively less sexy than calling myself ✨a writer.✨

But in all seriousness, I did some research and think I finally have an answer to the question, When can I call myself a writer? from a very reputable source:

I think it’s hard to call yourself a writer with your whole chest and mean it—at least it is offline for me. It can be a terribly subjective thing, wondering if and when you hit the right milestone, despite it often being exceedingly easy to fasten the label onto others. Case in point: I think Julianna is not only a certified writer, but a phenomenal one to boot.

I wanted to know:

Emily: In your words, what makes someone a real writer? Do you fit this definition?

Julianna: I think my answer to the question before this one is part of why I don’t think I’m a real writer. I write about real people in my life and things that have happened to me, but I worry that this makes me lazy because I don’t have, say, the skill or the desire to learn to create the characters or plan out the plots necessary for fiction writing. I feel like real writing involves a nimbleness or dexterity that I most certainly do not have after years of only writing about being Chinese, like there has to be some dullness in the way that I think.

It’s stupid because plenty of writers who don’t write fiction exist, and writing personal essays isn’t inherently easier, but I think I lack some sort of spirit of self-improvement or formal experimentation that a real writer is supposed to have.

When we spoke on the phone, you mentioned that maybe I am a real writer because, well, I write, and it resonates, and isn’t that enough? I think I will continue to grapple with this question for basically forever. If it’s based on effort and experimentation, then I won’t be real until I try to write fiction and/or take a class where I try much harder to improve. If it’s based on having an audience, then I won’t be real until I have X amount of subscribers or a book deal or whatever.

Maybe DM me if you think I’m a real writer—would love the input here.

I think if someone were to ask me right now where I see myself in five years, I would just start screaming. Think about it: in 2019, the biggest news was Trump’s first impeachment! Because of that, I do often feel bad asking people where they see their work in the future but I can’t help it. In my head, I frame the question like I’m asking my guests for their greatest hopes and dreams, not their concrete step-by-step plan for the future.

With all that said, I asked:

Emily: Where would you eventually want your writing to go?

Julianna: I think my mom wants me to publish a book and, if not a book, a podcast, a YouTube channel—something that generates revenue. We’ve butted heads about this a few times because I’ve told her that I don’t want to side-hustle-ify writing, but I think I’ve come to understand that her logic is, like, why work so hard and write so much for nothing to come of it?

Maybe it’s indicative of the kind of era I grew up in that I didn’t dream as much about having a novel as I did about becoming some sort of sceney It Girl with a profile in The Cut. It’s also worth noting I have horrible, horrible anxiety, and when I let myself be delusional and think about being “famous”—whether as a published author or a sceney It Girl—I just worry that someone would post, like, “Tea on Julianna Chen???” in a snark subreddit and then someone I went to college with would comment, “This chick sucks and her writing was always mid.” I don’t know.

I’m always confusing what I want with what I think can actually happen and what I think I’m actually capable of. When I think of the work that goes into publishing the book—writing the damn thing, finding an agent—I just don’t feel like that’s something that will ever happen for me, partly because I don’t know if I’m good enough and partly because I’m…lazy? And a person who actively thinks about Reddit hypotheticals?

But then there is this: when I was a kid, I was always stapling printer paper together to create “bound books,” and I’d write starred reviews for myself on the back like I saw on grownup novels: “Chen is a delight. -The New York Times.” So maybe six-year-old me knew desires I don’t yet understand.

While that would have been a lovely note to end on, I did have one more question for Julianna:

Emily: What are you working on next, and how do you feel about it?

Julianna: I am working on a little piece about my mom for Mother’s Day and a little piece about my dad for Father’s Day! I feel great about both of those because I think they’ll like what I have to say.

My mom also told me to consider writing something about our family dog Eli, who passed away almost a year ago. I feel less certain about that one—if only because he is a dead dog who can’t tell me if he likes what I have to say—but I’ll probably write it anyway because my mom told me to.

Thank you so so so much to Julianna for talking with me and for being such an absolutely brilliant writer!!!! Make sure to subscribe to lover not a writer!!!

Thank you too to Rebecca for guest editing today’s piece, and for still being my friend despite knowing me at 15!!! Check out Kid Girl and give her a follow, too!!!

A book I liked but did not love, simply for the focus on the protagonist’s Instagram comments section and how it read in the audiobook.