Therapize Your Darlings

This week I'm talking with a therapist...but what else is new?

Unfortunately, this post is too long to appear in full in your inbox. I don’t know where it will cut off in the email version, but it will be available online. See you there!!!

As many of you know—since I’ve said it no fewer than 3,429 times here on Emily For President—I genuinely get so excited to talk to friends who have gone back to school for some specialized focus or another. I’m in the era of life where I wake up in a cold sweat at 3 am every few days, desperate to answer the question: Should I go to graduate school?

Today, I’m all the more excited because we’re cracking into a previously undiscussed graduate degree and career track with a first-time guest—if I wasn’t such a chill, cool, fun, hot girl, I would absolutely be foaming at the mouth over this.

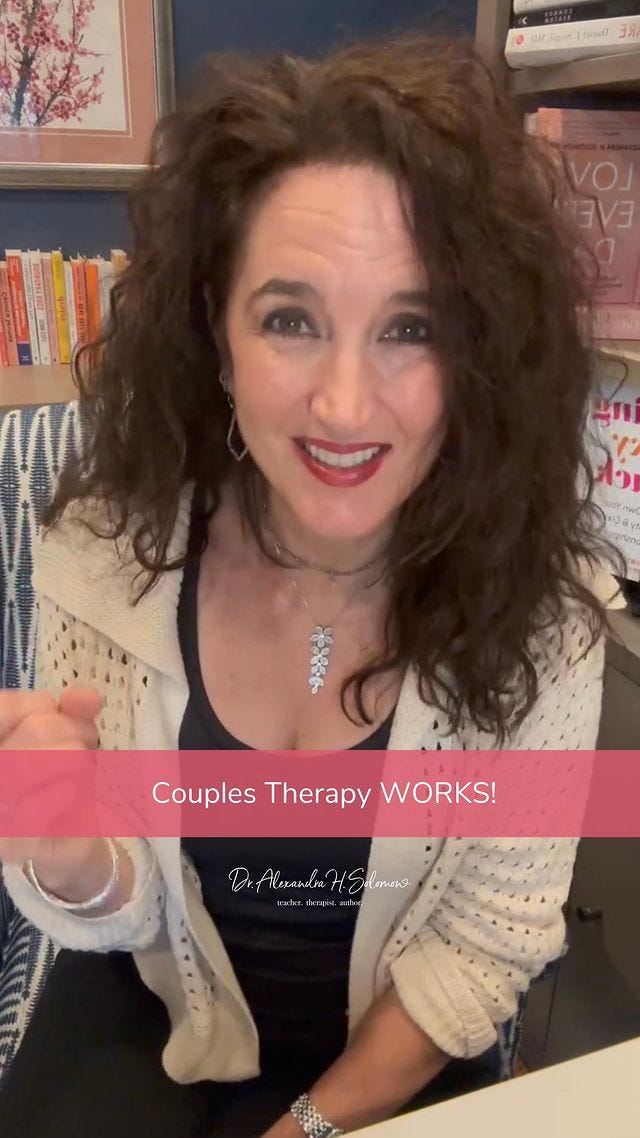

This week, I had the great fortune of talking with Nina Vargas about what led her to pursue a Masters of Social Work, why she wants to change the field of couples therapy, and which lessons from her personal therapeutic journey she hopes to bring to her practice.

Nina Vargas is a graduate student at Hunter College, soon to be receiving her MSW in May of 2024. She is currently working as a couples therapist at the Institute for Contemporary Psychotherapy within the Institute’s Family and Couples Training and Treatment division. She is a long-time relational dynamics enthusiast, Sagittarius sun/Sagittarius rising/Gemini moon, dedicated neo-soul and afrobeats fan, and ardent couples, individual, and family therapy advocate.

Couples Therapy For Beginners

Because my mom refused to get in the car with any of her children until they had their licenses, my dad taught all three of us how to drive. After every lesson behind the wheel with my brother, sister, or me, he would return home and triumphantly claim that he really missed his calling as a driving instructor.

Never mind that I would often be a few paces behind him in tears, having had my life flash before my eyes no fewer than two times each session (five when we went over reversing into a parking spot). But we survived and all passed our driving tests swimmingly so no further evidence is needed, your honor.

I say this because this is how I see people who say they think they’d make a good therapist. They’ve done one Put-a-Finger-Down challenge on TikTok that told them they were an empath, and before you know it, become fully convinced it’s time to switch careers.

As someone who has seen both The Undoing and three different therapists in her life—this is not counting the two who led my short-lived group therapy sessions as if it was the theater camp in the movie Theater Camp—I can attest that not all therapists are created equal. It takes a level of self-awareness that ✨empaths✨ don’t often possess to help a person learn to care for themselves and the world around them.

This is, however, the same reason why it makes perfect sense that today’s guest decided to pursue both her degree and her specialization. I wanted to kick things off today by asking Nina:

Emily: Did you always want to be a therapist? If not, what helped you get to this career path?

Nina: Yes and no…? I had no idea what I wanted to be for a long time and grew up really resenting the idea that I had to pick one thing. I studied acting in both high school and undergrad and by the time those eight consecutive years of training came to an end, I felt ready to (finally!) explore other interests of mine.

While studying acting, I discovered that what I loved just as much, if not more than actually performing, were my scene study classes. Sitting in a circle, dissecting plays, analyzing characters, trying to interpret a scene or a line was *chef’s kiss.* The human behavior and psychological elements of theater were so exciting to me.

In my five years post-grad, I’ve bounced around career-wise with a strong gut feeling that I would go back to school once I figured out what for. Several “aha” moments later, I decided to pursue my MSW to eventually become a psychotherapist.

Emily: What led you to want to be a couple's therapist specifically?

Nina: I was in my first serious relationship at 14 or 15 and the experience was really special in that I was very much in love with this person, felt very loved by them in return, and we were together for several years.

My second relationship was similarly timed in college (we started to date towards the end of freshman year and stayed together until graduation) and I was also very invested in and committed to that relationship, too. So from a young age, I was on the roller-coaster of serious/super euphoric/deeply painful when it ended, romantic love, having very big feelings, experiencing really dramatic highs and lows, and learning so much about myself in the process.

Around this time (and to this day, honestly), all I wanted to read were books on relationships—picture me fervently highlighting passages from The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm at 15—and all I wanted to watch were movies and shows that spoke to the mysteries, nuances, difficulties, and complexities of relationships.1 What I mostly wanted to talk about with friends were crushes, partnerships, hook-ups, break-ups, struggles in (and out of) love, and relational revelations.

To your question, I was always interested in relational dynamics and once I finally began to pursue a career as a therapist, couples work was front of mind.

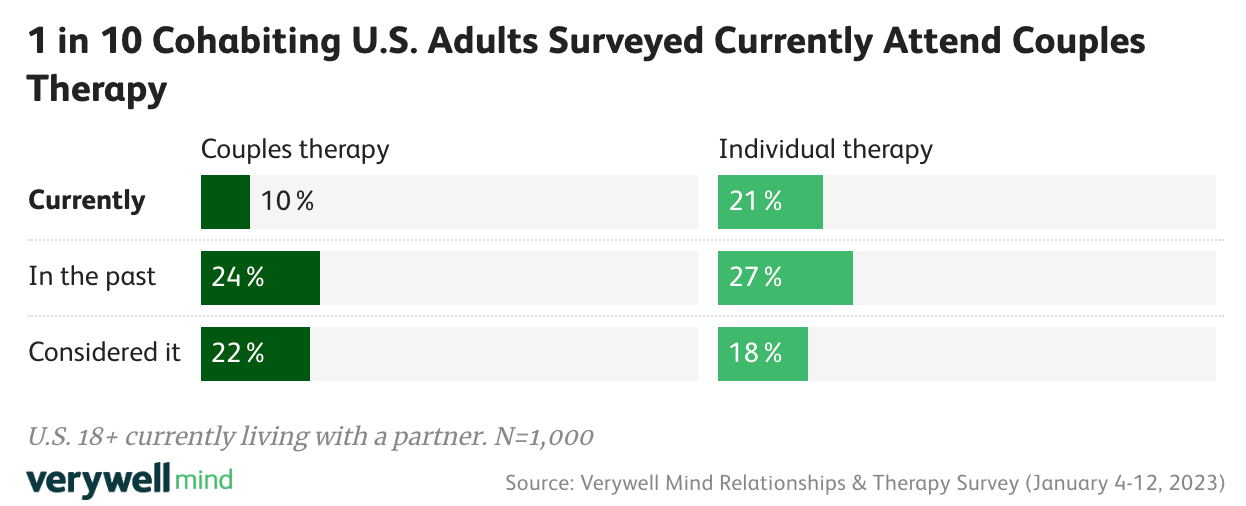

It’s harder than you think to find the exact numbers on how many couples in the United States seek out joint counseling but the most up-to-date information I’ve been able to find comes from online therapy provider, Well Marriage Center. As of this year, they reported that “nearly 49% of married couples report attending counseling together at some point in their relationship,” which makes sense when you also track changing opinions around couples therapy.

According to a meta-analysis published earlier this year,

three key factors have driven the development and widespread adoption of couple therapy as a prominent therapeutic modality. The first is the high prevalence of couple distress…The second factor prompting the rising profile of this set of methods is the adverse impact of relationship distress on the emotional and physical well‐being of adult partners and their offspring…A third factor propelling the prominence of couple therapy is the evolution of higher expectations for relationship life. Whereas once relational misery was simply to be tolerated, today couples have much higher expectations of relational life and see couple therapy as the pathway to better relationships (X).

The analysis then goes on to explain that

couple therapy also evolved in relation to sociocultural influences. Dowbiggin (2014) described a historical shift in couples' looking for guidance primarily from family and community to their seeking help from counseling professionals. He also suggested that marriage counseling—with its emphasis on personal happiness, sexual satisfaction, and more modern gender roles—both fit within and contributed to the cultural context of middle‐class 20th‐century America.

Doherty (2020) similarly situated the development of couple therapy in the context of 20th‐century family life, subject to larger system factors such as the rise in the divorce rate, the emergence of feminism, the explication of multicultural perspectives, and changes in American culture's view of marriage (X).

Couples therapy has also become increasingly favored as a tool for building healthier relationships largely because of the efforts of newer therapists, like Nina, who seek to invite all partnership dynamics into therapeutic practice and continue to reshape narratives around interpersonal relationships.

I imagine so many of us related to Nina’s rationale for why she was so intrigued by couples therapy—What I mostly wanted to talk about with friends were crushes, partnerships, hook-ups, break-ups, struggles in (and out of) love, and relational revelations—as that’s all stuff personally I do for free every day. To gain set strategies and vocabulary to make my relationships healthier, though, sounds like something a professional should guide me towards instead of the girlies after our fourth glass of white wine.

Remembering that Nina is actually the professional in the equation now, I wanted to know:

Emily: What are some of your goals as a couples therapist?

Nina: My main goal is to destigmatize and normalize couples therapy and couples issues in general.

Something that’s talked about a lot in the couples treatment world is that many couples pursue therapy together as a last-ditch effort to repair wounds that are, at that point, so deep. In other words, the experience is utilized as a sort of last resort versus an opportunity to get to know your partner and relationship more deeply when there is still mutual respect, tenderness, appreciation, hope, and compassion underneath all of the issues.

If you’re in a relationship, noticing some unhealthy or unhelpful patterns together, unsure about how to approach your differences, navigating a life stressor or big transition together, finding yourselves avoiding certain conversations because you can’t seem to talk about tricky or stressful things productively, arriving at communication impasses often, and/or in need of one dedicated hour a week where the health of your relationship is the only focus—I would highly recommend the experience.

Through my experience of talking about individual therapy, I’ve learned how the tides of that conversation have shifted so much that we’ve already managed to largely destigmatize therapy and then take things even further by desensitizing ourselves to mental health awareness. Yet, as Nina just explained, even as the way our society views couples therapy has evolved considerably, it hasn’t even gotten to the good part of the public opinion lifecycle yet and many people are still working off of inaccurate notions.

I wanted to set the record straight and ask:

Emily: What are some of the biggest misconceptions about couple's therapy?

Nina:

That it’s not affordable—and that goes for individual therapy, too.

That a couples therapist is going to fix your relationship problems. A way to reframe this misconception is by understanding that therapy aims to help people clarify their problems as opposed to solving them, and that while therapy isn’t always going to make you feel better, it’s hopefully going to help you get better at feeling.

That a couples therapist’s role is to figure out which partner is “right” and which partner is “wrong” when it comes to the issues the couple is bringing in.

That a couples therapist will side with one partner and make it harder for the other partner to feel seen and heard in the sessions and in the relationship.

That only people who are committed to making it work are eligible for couples therapy. Two people can also benefit from couples therapy for help negotiating their break-up or navigating co-parenting after a divorce, etc.

That the experience only makes sense for couples who are on the verge of breaking up and that if you “love each other” or “still plan to stay together,” it’s not necessary.

Shall I go on?

Nay—I believe this case is closed.

I <3 Therapy!

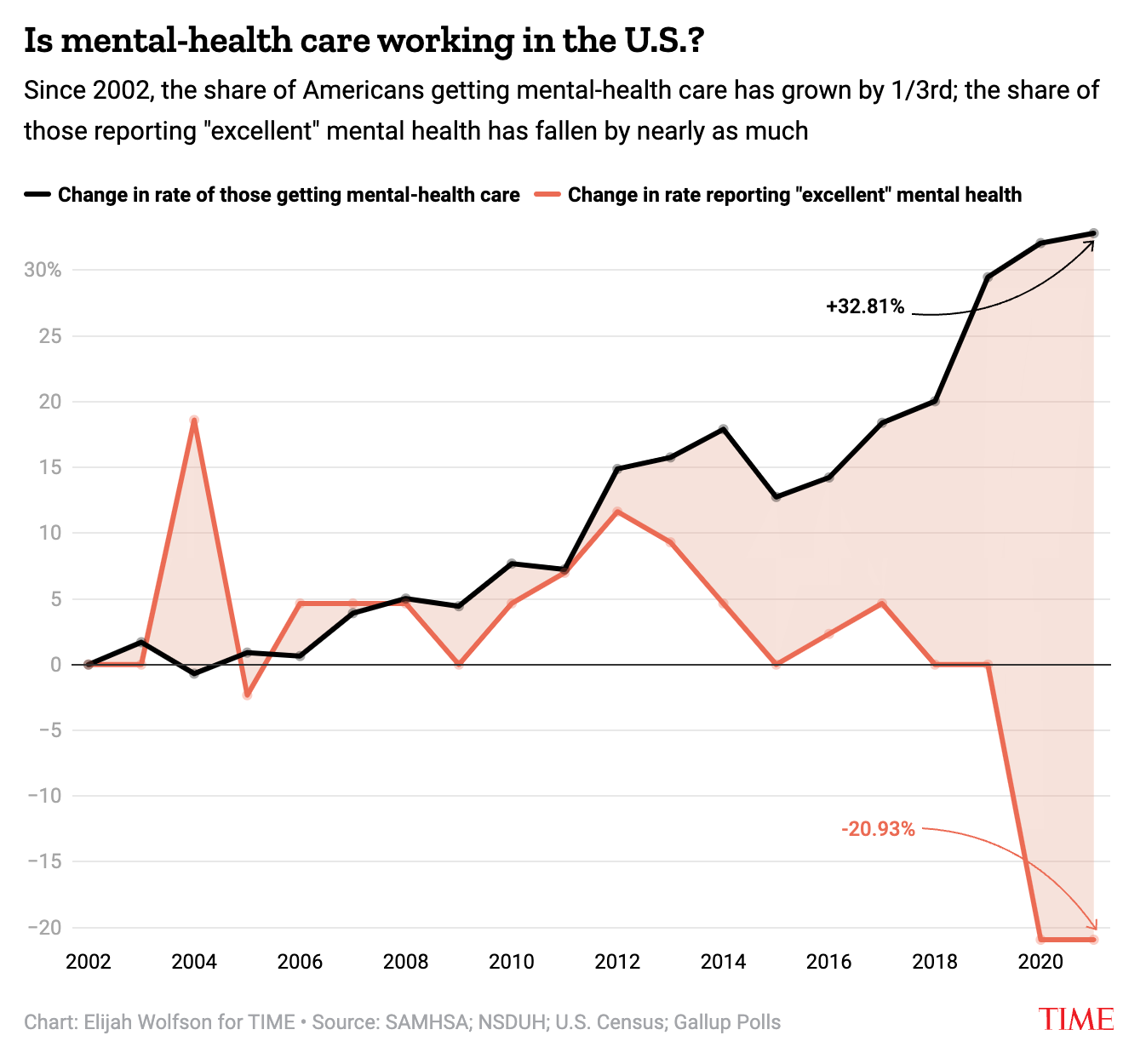

Last fall, the Centers for Disease Control shared that “the percentage of adults getting mental health treatment increased from 19.2% in 2019 to 21.6% in 2021,” with online therapy provider BetterHelp reporting that “over 41.7 million US adults saw a therapist in 2021.” Yet, as science and health journalist Jamie Ducharme explained in Time earlier this summer,

even as more people flock to therapy, U.S. mental health is getting worse by multiple metrics. Suicide rates have risen by about 30% since 2000. Almost a third of U.S. adults now report symptoms of either depression or anxiety, roughly three times as many as in 2019, and about one in 25 adults has a serious mental illness like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. As of late 2022, just 31% of U.S. adults considered their mental health “excellent,” down from 43% two decades earlier.

She goes on to write about how many experts believe that these stats are getting worse despite the destigmatization of mental healthcare because the original framework for modern psychiatry was not designed to provide us with the support we need now. Ducharme shares commentary from

Dr. Paul Minot, whose nearly four decades as a psychiatrist do not stop him from vocally critiquing the field, feels his industry is too quick to gloss over the "ambiguity" of mental health, presenting diagnoses as certain when in fact there's gray area. Indeed, research suggests both misdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are common in psychiatry. One 2019 study even concluded that the criteria underlying psychiatric diagnoses are “scientifically meaningless” due to their inconsistent metrics, overlapping symptoms, and limited scope. That's a sobering conclusion, because diagnosis largely determines treatment.

The American Psychiatric Association states that around 75% of those who try out psychotherapy have positive results but, as Ducharme highlights, “one of the best predictors of success in therapy…is the relationship between patient and provider—which may explain why it can feel like a crapshoot.”

As someone who has gotten lucky and had two really amazing therapists2, I’d like to propose a little hope for the future based on my experience (which is to say this is not 100% scientifically proven so don’t quote me on it): after my initial work with a therapist I saw through my university’s counseling center, I intentionally sought out younger therapists—half because I wanted them to get my cultural references and half because of their methodological approaches to our sessions.

I have personally benefitted from a combination of dialectical behavior therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy techniques, and have incorporated art therapy and meditation into my practices as well. The combo meal of all of this has worked so well at helping me manage my anxiety because they each offer strategies that are effective but allow me to be flexible enough that my efforts don’t themselves become anxiety-provoking.

Having talked with Nina about it, I know that combining modalities is a much more modern trend which has led me to wonder if the key to better therapy is a bit similar to what Gen Z hopes will happen for progressive legislation as conservative Boomers age: old habits of thinking and approaching therapy will wilt and give way to new growth.3

With all of this in mind, I asked Nina:

Emily: Can you speak to some of the tension points between old-school and new-school therapy practices, particularly when it comes to couples therapy?

Nina: Old-school approaches (think: Freud) often rely on well-established therapeutic models like psychoanalysis, psychodynamics, or behavioral therapy. Old-school therapists tended to approach sessions with clients as an anonymous, “all-knowing” expert. Their goal was to interpret, diagnose, and advise their patients.

Something that’s talked about a lot in this new(er) age is that old-school approaches focus on individual pathology and are less interested in the systemic and relational dynamics at play in a person’s life. You know: less attuned to different cultural impacts and influences on a person and more interested in what’s going on inside their heads.

New(er) age therapy approaches often integrate several different more contemporary modalities like CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), EFT (Emotionally-Focused Therapy), IFS (Internal Family Systems), Sensorimotor, and EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing).

An analogy: there are fitness trainers in the world who swear by one kind of workout with their clients (HIIT, pilates, or strength training), and there are others who appreciate several different kinds of workout techniques for different reasons and incorporate elements of each when they are training their clients. In this analogy, an “old school” therapist might be the former and the new school therapist would be the latter.

The “new-age” therapist’s role is also collaborative and empowering. New age therapy also welcomes the fact that the therapist is also a human being with feelings, fears, and pain from their present or past, that can also come up for them in sessions.4

I would also say the “new age” therapy world acknowledges the intersectionality of client identities and prioritizes cultural competency and systemic thinking. They want to know how institutional and systemic structures are influencing their patients.

A lot of what Nina has said about therapy at large and all that it can offer us has reminded me of my conversation with Ellie Haney from this past May. With that piece in mind, I wanted to ask Nina something a bit more personal to hopefully be (drum roll please) there for her:

Emily: What is it like to train to become a couple's therapist at this moment in time?

Nina: It’s very validating. Life is hard, relationships are hard, and our political and social landscape is…really depressing. The more people that are passionate about learning how to support others’ mental health the better off we all are.

Make Your Therapy Work for YOU!

As I quite literally just mentioned, I’m no stranger to talking about therapy here at E4P but I’ve never before had the chance to talk about it with an actual therapist. One thing my own therapist has told me that might not be as shocking to you all as it was to me is that therapists often go to therapy themselves. While my pea brain immediately thought, So like a therapist rat king, upon further critical thinking, it actually makes a lot of sense why therapists would want to continue seeking out space for themselves.

This led to me asking Nina:

Emily: Has your personal experience with therapy shaped how you approach practicing it yourself? If so, how?

Nina: I have a really wonderful therapist who works mostly somatically—in other words, she works with the body, is curious about where your feelings are living in your body, aims to get you back into your body, etc. It’s an approach that really works for me as someone who often intellectualizes their feelings…sometimes in an effort to avoid feeling my feelings.

I live in my head and am not shy when it comes to talking about my feelings. My therapist is someone who encourages me to shut my mouth and connect to my body, and it doesn’t usually take long for my feelings to emerge. It’s been such an important experience for me for so many reasons and in couples work specifically, slowing down happens to be one of the most important things a therapist can do to help a couple.

Couples are often activated and dysregulated in sessions because relationship problems can be—you guessed it—activating and dysregulating. My work is to sssslllllooooowwwww both partners down so they’re not getting carried away from their actual feelings that exist underneath the yelling/resentment/rage/pain/etc.

Emily: What are some things you wish clients knew about how to get the most out of their therapy sessions?

Nina: If you’re just starting therapy, take some time to reflect on your why. What are you hoping to get out of the experience? A therapist can help you figure out your treatment goals, but it’s always helpful if you’ve taken some time to think about them too. I don’t mean to contradict myself, but it’s also okay (and very normal) to feel unsure about why you are starting therapy or to be going because a loved one suggested you start. Either way, some reflecting before diving into the experience never hurts.

I would also say to check in with yourself before a session or ask your therapist if they know of any quick mindfulness techniques they can start your sessions with. I say this because it can be easy to eat up the hour with small talk (especially on the weeks that you might feel like there’s nothing pressing you need to discuss or when there are difficult feelings coming up for you that you prefer to avoid).

Checking in with yourself 5-10 minutes before a session (closing your eyes and asking yourself how you’re doing and noticing what comes up can sometimes provide us with a great agenda). If we are rushing to our session, itching for it to be over because of something we have going on afterward, or flying through it to “get it out of the way,” we might be making it harder to progress.

We all have relationships—coupled or otherwise—and while I don’t mean to give away Nina’s therapeutic practice for free, I did want to know if and how her work has influenced her own life:

Emily: What are some things about interpersonal dynamics you've learned through your work that you wish more people knew? Have you taken anything you've learned in your studies or budding practice and applied it to your own relationships? If so, what?

Nina: Active listening is a skill that will take your relationships very far, relational conflict is normal—inevitable, even—and managing conflicts is a much more realistic goal in relationships than solving conflicts. Never underestimate the power of humor in your relationships, get good at apologizing, figure out what you need in your relationships, and stay curious about why you need these things.

Flexibility and adaptability in relationships are major strengths, it’s not unusual for two people to need to reconfigure their relationship multiple times over the relationship’s life cycle, individual growth supports relationship growth, all relationships require effort, and here’s a favorite of mine: all relationship problems between two people are, to an extent, co-created.

This can be a hard one to entertain, but I encourage you to stay open to it. It can be a fruitful piece of wisdom—especially in your loving relationships—if you let it.

To close out today’s piece on a high note, I did the most obvious thing I possibly could—I took advantage of the rare chance to ask a therapist my most burning therapy-related question:

Emily: In your professional opinion, should all men be in therapy?

Nina: Hehe, why not?

Thank you so so so much to Nina for not only being brilliant and gorgeous but also one of the kindest and most supportive people I know!!!! I’m so proud of her, having watched this career journey from where she started to now, and I’m thrilled E4P officially has a Resident Therapist—whether Nina realizes it or not!

Shoutout Blue is the Warmest Color.

I said what I said…you can run those numbers, they check out.

Come on—it wouldn’t be an E4P installment if conservatives and Boomers weren’t catching strays.

Sidenote: It’s still their job to manage their feelings and prevent them from taking over in sessions because the experience is not about them, it’s about their clients.