Writing this piece—which is, if I do say so myself, very serious and scholarly—the day after something as unserious as the Grammy Awards feels a little disorienting. Here I am talking about murder and racism less than 24 hours after…that happened.1

I’m by myself this week so I wanted to look into a phenomenon I’ve been fascinated with for a while now: the explosion of the true-crime genre. As someone whose listening digest is almost exclusively just audiobooks and Keep It!, I have the luxury of being an outsider casually and impersonally observing everyone else who cleans and exercises to retellings of violent and gory murders. And, as someone who is very much an insider on the internet, I’ve also seen how the popularity of those violent and gory murder retellings can lead to justice, resolution, and closure.

That’s why today, we are looking into why everyone is so obsessed with true crime, what role the “missing white woman syndrome” plays in which cases get more attention, and how all of this factors into the recent University of Idaho murder case.

Psychology? TODAY?!?!

If you, like me, are wondering how we got to this moment in culture rife with cold cases and cold bodies (my first and last corpse joke of the day, don’t worry), most sources cite the release of Serial as the catalyst for the current true-crime craze. As for the why driving the genre’s surge in popularity, the answer becomes a lot more nuanced.

It may or may not surprise you all to hear that women are driving the current true-crime phenomenon: according to a YouGov poll from last year, women are more likely than men to consume true-crime content by a margin of 58% to 42%. In her 2019 study which focused on why this is, professor Amanda Vicary found that

women all seemed to like reading about survival, whether it was preventing or surviving a crime…Research shows that women fear crime more than men, since they're more likely to be a victim of one. My thinking is that this fear is leading women, even subconsciously, to be interested in true crime, because they want to learn how to prevent it (X).

In a Psychology Today article about the uptick in content centered around serial killers, criminologist Scott Bann seconded Vicary’s conclusion by arguing that “the public is drawn to serial killers because they trigger the most basic and powerful emotion in all of us—fear. As a source of popular-culture entertainment, serial killers allow us to experience fear and horror in a controlled environment, where the threat is exciting, but not real.”

With most true crime content, consumers are often less separated from the crimes in terms of time (think: watching a show about Jeffrey Dahmer’s crimes in the 1980s and 90s versus watching an episode of 20/20 about the Idaho murders) so it almost feels like you can glean a lesson on how not to end up in a future episode yourself.2

Additionally, the true crime content itself is what popularizes cases. Relying once again on the Dahmer comparison as an example, his story has already been well-known for decades at this point, so more content about it does nothing for anyone except, maybe, Ryan Murphy. When listeners hear a podcast about a cold case or read a news article about a recent string of murders, “many of us put on our ‘armchair detective’ hats [and] we’re prepared to pore over every detail of a case in hopes of cracking it wide open. This is, in part, due to the fact that our brains love puzzles and having problems to solve. But another aspect of this tendency is to see to it that the ‘bad guy’ gets held accountable for his or her horrific actions” (X).

Before I get into the “why the real ‘bad guy’ may be us” section that we all know is inevitable here at E4P, I do want to highlight some of the good that our society’s current obsession with true-crime has done: last fall, Adnan Syed—the man at the center of the viral first season of Serial—”walked free after a Maryland judge vacated his 2000 conviction for the murder of Hae Min Lee” (X), which led Syed’s lawyer, Justin Brown, to tell The Washington Post, "‘I always get asked the question, “Did Serial help the case?” It absolutely did help’" (X).

Kelli Boling, an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, also told Scripps News that

there are more true-crime podcasts that have exonerated wrongly convicted people. On the other side, they've also found, you know, perpetrators that did these crimes via DNA evidence. So, yes, there's good coming from the genre and people are attracted to it because they want to see justice served.

So, while loving true crime can, therefore, arguably save lives, it also very simply scratches an itch that we can’t reach any other way. No sane person would put themselves in the same dangerous situations as the ones they listen to or read about, so instead, they get their adrenaline rush from a third-party source who typically has a very soothing and inviting voice.

One problem that arises from this, though, is the makeup of the cases that generate national buzz. All cases, especially those in which someone has lost their life, deserve to be solved. But in the eyes and ears of true-crime fans, there is one victim demographic that is consistently worth saving.

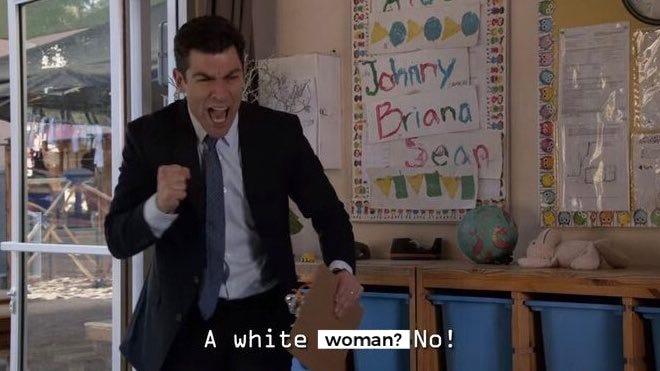

A White Woman? NO!

Following the 2021 disappearance and murder of Gabby Petito, one of the primary conversations that came to the forefront was why unsolved cases tend to receive more public attention, action, and sympathy when the victim is a young white woman. Detracters detracted but the point was undeniably proven less than six months later when Lauren Smith-Fields was found murdered in a similar mysterious fashion, yet it took an invested and determined internet campaign to generate only a modicum of the national attention Petito organically received.3

Unsurprisingly, this phenomenon-within-a-phenomenon is so common that it already has a name—“missing white woman syndrome”—and has even been studied.

In a 2021 interview for the New Yorker with Queensborough Community College professor Jean Murley, writer Helen Rosner stated that “cases that get this exponentially greater level of coverage tend to have, at their center, white women, and especially younger and conventionally attractive white women,” to which Murley replied:

That’s an undeniable fact. There’s something about the missing young, beautiful white woman that has a lot of symbolic weight in America. It’s an aberration, and it becomes a container for things like the loss of innocence or the death of purity. This has a long historical trajectory, starting with the lost colony of Roanoke, Virginia. That was the birthplace of the first Englishwoman born in America, a little girl called Virginia Dare. That character of Baby Virginia has been mythologized and heavily inscribed with all sorts of meaning. No one ever knew what happened to the colony she was a member of, and so she has come to stand for the dangers of America, the dangers of the wilderness—that history starts with the missing white child, Virginia Dare.

Murley then explains how this original concept evolved throughout American history, further mythologizing the importance of white women’s safety. What’s significant about this is that as the myth became more entrenched in the cultural narrative, the more misleading it became: when responding to Rosner’s next question, Murley states that much of the true-crime genre is

white America telling itself a story about danger and violence and womanhood, when the fact is that most homicide victims in this country are young men of color, and those stories don’t get told, by and large. They just get ignored, they get trivialized: “Oh, it’s drugs, crime, gangs, urban violence.” But then a white woman goes missing, and that’s a big deal.

Boling further explains that white women then, in turn, continue to drive the true-crime genre because

a lot of true crime is built off of media coverage…Where the media has been shown to cover White victims more than victims of color in plenty of studies across decades. That continues to be the case. So, if the media are covering mostly White female heterosexual victims, then that's what true crime is producing off of, because that's the media that they have access to. And so then they are attracting an audience that looks like that (X).

It’s a little bit like the chicken and the egg: our society has been historically conditioned to care more about the safety of white women than other demographics, so that’s what the media covers. As white women follow these cases, ostensibly for protection or comfort, their consumption drives true-crime creators to focus on solving these crimes, making them the most popular and perpetuating the belief that we all care more about the safety of white women than other demographics.

The solution is obviously not to make more targeted appeals to different demographics, begging them to care about cases with individuals who share similar identities, but—once again—for white women to use the power they hold for good. If their interest in cases is what regularly leads to uncovering the truth via media attention and law enforcement resources (and that if is pulling a lot of weight to describe a very clear fact), then white women can and should consume more true-crime content about victims who don’t look like them and call for more if they’re not seeing it available.

Ok, I Get It. But Why Idaho?

The murders that took place last November at the University of Idaho are, unfortunately, the perfect example of everything we’ve covered here so far.

On the morning of November 13, four students at the University of Idaho—three women and one man—were stabbed to death in their off-campus house. The case immediately became the topic of national discussion due most obviously to its sensationalist and gruesome matter but also likely in part to the fact that all of the victims were young, attractive, and white.

For the nearly six weeks that followed, the Moscow, Idaho police were incredibly tight-lipped about details of the case, arguing that they didn’t want the murderer, who was still at large, to know exactly how much those investigating the crime knew. As a result, the case became fodder for the true-crime community who took to Reddit and TikTok, in particular, to try to uncover the truth of what happened before the police did. According to the case’s Wikipedia page,

a phone tip line and email were created for students and others to submit potential evidence to officials. As of December 5, it was reported that there had been more than 2,600 emailed tips, 2,700 phone calls, and 1,000 digital media submissions from the public to these tip lines. On December 24, the investigative team reported having received at least 15,000 tips regarding the case.

However, during last month’s episode of 20/20 dedicated to the Idaho murders, the conversation repeatedly returned to the fact that in their attempts to solve the murders, true-crime fans actually spread misinformation about the case online. In a Spokesman-Review article posted a week after the murders, journalist Emma Epperly looked at this development, finding that

some people from as far away as South Carolina created Facebook groups to share theories about the case that quickly garnered thousands of members. People anonymously posted the faces and names on Reddit of twenty-somethings who knew the victims, accusing them of the horrible crimes.

Earlier in the piece, Epperly also included a quote from Ben Shors, the chair of the Department of Journalism and Media Production at Washington State University: “‘Rumor loves a vacuum…So often what we elevate are controversial voices opposed to fact, especially when facts are so limited.’” Some of the voices claimed a University of Idaho professor committed the murders, others claimed it was one of the victims’ stalkers, and a few even circulated the claim that one of the victims killed the others before taking their own life.

None of these theories were true: the murderer was revealed to be a Washington State University PhD student named Bryan Kohberger who, at this time, is not thought to be the alleged stalker, a professor to any of the students, or one of the deceased himself as he has been arrested and is awaiting trial, very much alive.

What’s most troubling is that the psychology of true crime seems to go both ways in this case: just as internet detectives tried to solve his crime themselves, Kohberger very obviously applied what he had learned as a psychology and criminal justice student to his murders. His phone was turned off for the hours allegedly surrounding the attack so its location couldn’t be traced, his license plate had been changed soon after November 13 which originally threw investigators off his tracks (according to claims made in the 20/20 story), and he was allegedly in and out of the murder scene within 25 minutes, which he entered without leaving behind any signs of forced entry.

Then again, some of Kohberger’s actions could indicate to some that he—just like all the amateur detectives online—might be too confident in his criminology skills: he not only allegedly drove past the scene of the crime at least a dozen times in the months leading up to the crime, but he returned to it a few hours after the murders had been committed; he also left a piece of evidence allegedly with his DNA at the scene of the crime and suspiciously threw out garbage in a neighbors trash bin before very publicly cleaning “‘his car, inside and outside, not missing an inch [of area]’” (X).4

Now, as his team takes the next four months to build their defense, no new information is likely to come out. Except that it is.

The public’s investment in this case is so strong that it seemingly can’t be turned off. Internet sleuths everywhere and across every channel are determined to figure out the mystery of the surviving roommate’s 911 phone call, and the significance of what was in Kohberger’s trash, and which victim fought back the hardest, and was Kohberger on the university’s campus before the murders?, and worst of all, the case’s popularity has earned Kohberger an admirer who is also getting attention.

I’m not sure what the right response is: how do you tell someone who cares so much about something to just care less, especially when those people have an emotional connection to making sure justice is served? (Excluding, obviously, Kohberger’s Bundy-esque admirer.) Is this just what happens after investing so much time and energy into a true-crime story?

If Bobbi Miller—an entertainment expert who focuses on ethical true crime consumption—is to be believed, then the answer here is yes…kind of? Miller states that “ethical true crime stories…are the ones that focus on victims and don’t center the criminal as some cult of personality or mysterious mind to untangle,” but stops short of discussing what the ethics are when we just can’t seem to let a case go.

I don’t have a clear answer, nor could I seem to find anyone with one. It just seems like once a true-crime story achieves mainstream popularity and discourse, it becomes just another news report for us to return to as often or as infrequently as we’d like.

You’ve Critiqued and Analyzed—Please Tell Us There’s A Hopeful Resolution to End On???

Kind of.

In an article last year about Adnan Syed’s release for The Guardian, journalist Adrian Horton explained that

There will always be schlocky true crime documentaries, TV series and podcasts – entertainment appealing to the base human interest in spectacle, vicarious trauma or the futile quest to map a serial killer’s psychology…But true crime content has, in part, matured from obsessive dissection of individual stories to critiques of the system at large.

We can see this a bit with the Idaho case: while it didn’t necessarily have the intended effect, the people investigating the murders online felt like they were doing what the police weren’t. The problem, though, is that there was the same kind of public response from those investigating the Idaho murders as there was from those investigating Lauren Smith-Fields' murder, but due to a lack of true-crime notoriety, there was less taking place behind the scenes in her case and a greater delay in action taken to solve her death. It wasn’t until her friends turned to TikTok and generated attention on their own that the media finally took note of what had happened to Smith-Fields and began to cover it…three months after the fact.

The amount of attention and law enforcement resources allocated to solving cases should not be contingent on popularity within the true-crime community. While it is great that fans of the genre are recognizing flaws in our criminal justice system and bringing awareness to them, our society still often neglects to recognize that these true-crime “stories” are not just cautionary tales or puzzles to solve, but people’s real lives and deaths.

I don’t want to judge anyone’s interests nor would I ever dare make the argument to abandon true-crime content altogether. In fact, I don’t even have a concrete “last thing” to say. I thought researching this phenomenon would offer me some clear-cut, resolute opinion but in all honesty, I feel even more confused about where I stand than when I started.

I won’t say treat people with kindness because I can read a room, but I will say this: perhaps we should all treat others the way we would want our own true-crime stories to be treated. Maybe that’s all there is to say.

We are absolutely not unpacking this any further. I always have and always will love Harry… but Renaissance is MY album of the year.

As the Forbes interview with Vicary states, “More than anything, women wanted to know either the psychology of the killer or specific survival skills they could use to escape one.”

The facts of Smith-Fields’ case are horrifying: one NYT article covering it states that “the family had to beg the detective to collect evidence found in the apartment, their lawyer said. The detective also told the family not to worry about the man who had been there that night, saying that he was ‘a really nice guy,’ Ms. Fields said. ‘My daughter’s laying there dead and he gets to walk away,’ she said.”

The car was a major piece of evidence against Kohberger as there was concrete evidence of its presence at the victims’ home on the night of the murders.