It's the Economy, Stupid

Do you understand how bad things need to be for me—ME—to actually learn about economics in earnest?? To understand tax codes and the SALT Deduction??? To talk about TARIFFS????

As is the case every week, I find myself with 295,050,786 things we could potentially talk about in today’s piece. But instead of getting into any (or, frankly, all) of the topics that are immediately relevant and ripe for discussion, we are going to have a conversation I’ve been procrastinating for a few weeks.

I have long brought shame to my family (my father) for not living up to the potential they had hoped for me (I never took an economics course in school). Today, I finally have to confront my shortcomings because I’m getting really pissed off. Following Donald Trump’s re-election last month, one person too many got on my Internet feed despite my carefully trained algorithm and talked about voting for him “because of the economy.”

It’s fair to say the economy was the most biggest issue for voters this election, as a Gallup poll from mid-October found that 99% of respondents listed it as at least somewhat important to how they were casting their ballot. But as someone who grew up with a basic understanding of how our economy functions—much to my own dismay—I found a lot of the pro-Trump economic commentary to be a bit cocky.

Suddenly, everyone’s an expert on tax codes and inflation…so I thought I would become one, too.

This week, I pointedly did not interview my dad because I wanted to approach this piece as if I weren’t an economist nepo baby. Instead, I did my own research the way anyone else with access to Google would figure out what our economy looks like right now, what shapes the American public’s perception of it, and what effect Trump’s plans and policies could have over the course of his next term.

What in the fuck is a tariff?

Ok, I like where your head is at, but let’s take this one step at a time.

Sure, sure. Let’s start with…what does our economy look like today?

It’s my understanding the US economy is actually on an upswing, relatively speaking. In a piece for the Wall Street Journal on October 31 of this year, their Chief Economics Commentator Greg Ip wrote that

with another solid performance in the third quarter, the U.S. has grown 2.7% over the past year. It is outrunning every other major developed economy, not to mention its own historical growth rate.

More impressive than the rate of growth is its quality. This growth didn’t come solely from using up finite supplies of labor and other resources, which could fuel inflation. Instead, it came from making people and businesses more productive.

This combination, if sustained, will be a wind at the back of the next president. Three of the past four newcomers to the White House took office in or around a recession (the exception was Donald Trump, in 2017), which consumed much of their first-term agenda. The next president should be free of that burden.

Meanwhile, higher productivity growth should make the economy a bit less prone to inflation, more capable of sustaining budget deficits, and more likely to deliver strong wages.

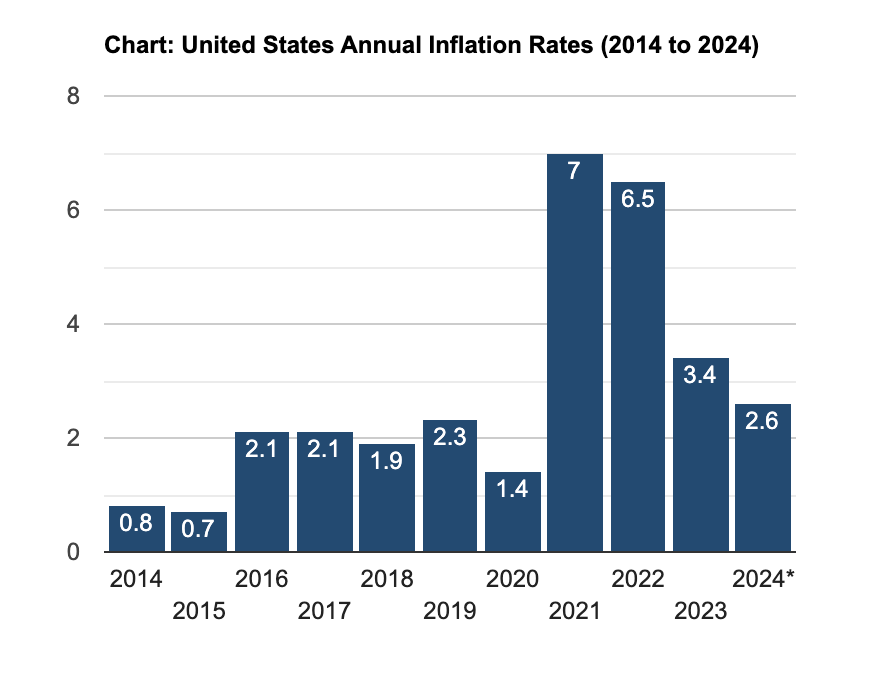

More to it, the following chart from the US Inflation Calculator—a website dedicated solely to inflation-related news—indicates that inflation has continued to decrease significantly over the past year:

For the sake of transparency, I will admit that at this point in my research, I did Google, What is inflation? In my defense, I did and do know what it is but it has become such a buzzword over the past few years that I began to question my own modest handle on economics. In case you’re at all like me, inflation is “the rate of increase in prices over a given period of time. Inflation is typically a broad measure, such as the overall increase in prices or the increase in the cost of living in a country” (X).

If the rate at which prices increase is actually on a decline and the economy is in “excellent shape,” then you might be wondering why so many people claimed they were voting for Trump because groceries under Joe Biden’s presidency are too expensive. There are a couple of reasons for this.

The first is that they wanted to vote for Trump anyway but didn’t want to cop to that so they just said, “The economy!” instead. The second is that even though the rate of inflation is down, “employment and consumer spending have stayed strong, and wages have on average grown faster than prices,” many Americans still genuinely believe the economy is in bad shape. As Ip explains, “to describe this economy as remarkable would strike most Americans as confusing, if not insulting,” as a pre-election Wall Street Journal poll found that “62% of respondents rated the economy as ‘not so good or ‘poor.’” Which is to say—there are people who genuinely believe any change from the Biden-Harris administration would be good for the economy.

There’s a part of my brain that wanted to write off that belief as the result of successful GOP marketing, but several sources I found touched on a psychological component: one Wall Street Journal piece argued that

people find it unsettling that price tags don’t look like they did before inflation took off during the pandemic, surging to the highest level in four decades. Even though the growth in prices has eased significantly, prices themselves aren’t getting lower…

Americans are grappling with dramatic price hikes that, for most, are unprecedented. In the latest surge, inflation peaked in mid-2022, with prices up more than 9% from a year earlier. In the years prior to the pandemic, inflation was unusually cool, and the last time it was a real problem was the 1970s and early ’80s. That means most Americans weren’t yet born or were children when worries over prices were last omnipresent—along with disco balls and bell bottoms.

A CBS News article also explained that

many Americans not[ed] in exit polls on Tuesday that they're still hurting from the highest inflation in 40 years and dissatisfied with the nation's economic trajectory.

Trump ran on a campaign that vowed to tackle those issues, pledging to end the "inflation nightmare" and to bring prices down "very quickly."

With all of this said, what I wanted to make sense of next is how we could have a strong—or strengthening, if you’re not feeling particularly generous—economy and there are still so many people who don’t see it that way.

Because inflation was so high during Biden’s presidency (see: the US Inflation Calculator’s chart for years 2021 and 2022), a lot of Americans have blamed him for the higher prices. As Derek Saul explained in Forbes before the election last month, “Voters usually punish presidents when the economy is poor and reward presidents when the economy is strong, but no matter who sits in the Oval Office, their actual power over economic conditions is limited.” With this, you can imagine what voters who want to “punish Biden” for inflation would think when they learn that Harris’ proposed economic agenda would have carried “forward much of President Biden’s FY 2025 budget, including higher taxes aimed at businesses and high earners” (X).

I don’t want to gloss over the major reason many Americans did not want to vote for Kamala Harris so I’ll explicitly say it’s because she’s a Black and South Asian woman, but you can see how some people could justify a vote for Trump by a desire to ease their economic difficulties. I’m not particularly keen on relying on polls anymore, but an exit poll conducted by CBS News found that 73% of those interviewed voted for Trump because change was important to them. In that same exit poll, “three-quarters of voters said inflation was a hardship.”

Yes, Trump is obviously a change from the Biden-Harris administration, but is he going to bring about the exact economic change some people are looking to him for? From what I’ve been able to gather, the answer to that question is probably not in the exact way voters imagine it will be.

This is because the blame for the economic hardships many Americans still see themselves facing does not rest all that heavily on Joe Biden.

So…if Biden’s economic policies weren’t primarily responsible for the economic conditions that so many people voted against this year, then who was?

Last month, USA Today interviewed seven economists and asked them if the Biden-Harris administration was to blame for the inflation spike two years ago:

Yes, the economists said, but only to a degree. Of the seven economists who spoke to USA TODAY, most cited the global pandemic, not Biden, as the primary cause of the nation's inflation crisis…

The pandemic triggered a brief recession, followed by a round of global inflation. The Trump and Biden administrations both responded to the downturn with multiple rounds of stimulus aid, dispatching checks to American homes. The Federal Reserve lowered interest rates and pumped money into the economy. Their collective aim, economists said, was to avoid a repeat of the Great Recession of 2008, which hobbled the U.S. economy for years…1

Biden and the Fed succeeded at pulling the economy out of the downturn. The job market swiftly stabilized. But the stimulus also fed inflation, the economists said, which ultimately helped sink the Democrats at the polls…

Yet, most economists queried by USA TODAY listed the pandemic as the main reason for the historic price surge. Inflation, they said, would have happened no matter who was president.

“There’s a long list of reasons for the high inflation,” [chief economist at Moody’s Analytics Mark] Zandi said. “The Biden-Harris policies that are on the list are at the very bottom.”

The rest of the article sees the economists debating the degree to which Biden’s decision to administer a third stimulus check was a net help or hindrance, as well as how much of the rise in inflation was inevitable as a result of the geopolitical developments like the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It also explains the Federal Reserve’s involvement and how it shaped inflation rates outside of Joe Biden’s actions.

With this last point in mind, I found the piece starts to touch on but doesn’t fully address how much direct power the president has over the economy. Now, just as the last section wasn’t an attempt to ignore the role bigotry played in voters’ reluctance to elect Harris, so too is this section not an apology for Joe Biden’s wrongdoings as president because babes…that’s not my fight to fight.

When we see politicians on the campaign trail, they talk about taxes and who inherited whose economy and cuts and codes and caps—AHHHHHHHHHH oh my! This is interesting to me because when it comes to proposing and passing new taxes, the president is largely not involved in the process until the very end. Taxes (how much we pay of them, where they are spent, why we should teach people how to file them correctly so we don’t end up accidentally committing tax fraud2) are determined by Congress:

The power to tax is found in the U.S. Constitution. The word tax appears at least ten times in the Constitution, but we typically focus on Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, the so-called “Tax and Spend Clause.” It begins:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

And the explanation for how that begins is laid out in Article 1 at Section 7, Clause 1:

All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments as on other Bills.

Every bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a law, be presented to the President of the United States…

In other words, the President isn’t tasked with drafting tax legislation—that’s Congress’ job (X).

Mike Walden, a Professor Emeritus at North Carolina State University, offered a great explainer in September that lays out who determines federal fiscal policy (Congress) and who determines federal monetary policy (the Federal Reserve). Walden writes that

a president has influence over both fiscal policy and monetary policy, but the influence is indirect. Fiscal policy is implemented through the federal budget. While a president can make recommendations about the budget, ultimately both chambers of Congress must pass the budget. This often results in long negotiations between a president and both chambers and all political parties in Congress.

For monetary policy and the Federal Reserve, a president does have the power to appoint the members of the governing body of the Fed (with the consent of the Senate), called the Board of Governors…While this may imply the president has major control over the Fed, this actually isn’t the case. The reason is the term of the board members is long, at 14 years. This is longer than two full terms of a president…It is thought the framers of the Fed over a century ago purposefully made presidential influence over the Fed difficult in order to insulate monetary policy from political influence. The Fed is also independent from Congress, due to the fact that Congress does not fund the Fed…

The conclusion is a president’s powers over the economy are limited, especially with the two major tools of fiscal policy and monetary policy. However, there is another source of presidential influence that shouldn’t be overlooked. This is a president’s use of the “bully pulpit,” a term coined by Theodore Roosevelt to mean a president advocating policies using speeches and interviews. The goal is to generate public support for policies and public pressure on Congress to agree with a president’s ideas and recommendations.

A president doesn’t guide the economy like an executive or manager guides a company. A president has influence over the economy, but the influence is indirect through working with Congress, making appointments to the Federal Reserve and rallying support from the public. So while the economic ideas of a president are certainly important, the reality is that it takes more than that one person—even a very powerful person—to move the economy. There are many, many hands on the oar of the economic ship (X).

When we talk about the economy in a political sense, it makes sense to tie its developments to whoever is in the Oval Office at the time. However, the economy moves in mysterious ways and is changing all the time, sometimes in ways that are not immediately political3—for better or worse, that is what you get with capitalism! Unfortunately, my dad was on the money (pun intended) in 2021 when he told me:

Emily: Is the economy ever chilling? Not moving from trough to peak but just kind of steady?

Bill: The economy is about life. It’s a reflection of people’s behavior. Is your life ever stagnant?

Emily: No.

Bill: No.

Emily: So we’re not talking about money, we’re talking about the meaning of life.

Bill: You, my unfortunate daughter, have decided to ignore my suggestions to understand economics and now you have no idea what the meaning of life is.

With all of that said, Trump is taking office at a time when our economic policies are due to shift, and he’s coming back with his party in control of the House and the Senate. Even if he is not the one proposing and negotiating the exact plan, what he wants for the economy can ultimately be significant.

Are you talking about tax codes? Because I keep hearing about tax codes and that ours expires next year. What does that mean for the economy?

Very simply, “the term ‘tax code’ refers to a series of laws and regulations that outline the rights and responsibilities of the general public as they relate to taxation” (X).

Trump played a key role in negotiating—and therefore building—our current tax code in 2017 which is known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The TCJA

was the largest tax code overhaul in nearly three decades. The law cut the corporate tax rate to 21%, capped deductions for state and local taxes (SALT) at $10,000, doubled standard deductions, and expanded the child tax credit.

The goal of the one and a half trillion-dollar tax reform bill was to spur economic growth, reduce regulations, and create a more business-friendly environment in the U.S.

The TCJA was passed as reconciliation legislation, meaning the bill overrode typical filibuster rules and was passed by a Republican-led Senate with a simple majority of 51 votes. However, many provisions were made temporary to keep costs down and comply with the Byrd Rule, which prohibits reconciliation bills from raising the federal deficit beyond a 10-year budget window or making changes to Social Security (X).

As a result of that bureaucratic loophole, a large chunk of our existing tax code expires next year, and while Trump is looking to keep a lot of it the same, he has also indicated he wants lawmakers to make a handful of key changes.

It’s my understanding that Trump wants certain expiring elements of the TCJA to be made permanent now that Congress has a Republican majority in both chambers:

While the 21% [corporate] tax rate is permanent, his 2017 individual tax cuts for individuals are set to expire after 2025. Those cuts overwhelmingly benefit wealthy households, small business owners and those in the real estate industry (X).

But Trump is also calling to repeal parts of the TCJA, namely the SALT deduction (SALT stands for state and local tax). According to the Tax Policy Center, the TCJA “significantly increased federal standard deduction amounts (thereby reducing the number of taxpayers who itemize deductions) and capped the total SALT deduction at $10,000.” An article in Mansion Global (ironically??) explained the rationale for this policy the clearest:

Before 2018, the SALT deduction allowed individuals to deduct an unlimited amount of local property and income taxes from their federally taxable income. The TCJA limited the amount those taxpayers could deduct to $10,000, primarily targeting higher-income households who itemize their deductions.

Capping the SALT deduction at $10,000 was intended to benefit middle- and low-income households, as the TCJA “disproportionately impacted residents, particularly homeowners, in high-tax blue states like New York, New Jersey and California, while raising billions of dollars to offset the TCJA’s generous tax cuts” (X).

So if Trump is able to get Republicans to repeal the cap as proposed, the Tax Policy Center

estimated that households making about $63,000 or less (those with the lowest 40 percent of income) would get no tax cut on average. Fewer than 1 percent of them would get any tax cut at all.

About 5 percent of middle-income households, those making between about $63,000 and $113,000, would benefit from the SALT cap repeal. Among all households in that income group, their average 2025 tax cut would be $30. Low- and middle-income households would hardly benefit because their state and local tax bills are relatively low and because the TCJA greatly increased the standard deduction…

[Repealing the cap] would cut 2025 taxes by an average of more than $140,000 for the highest-income 0.1 percent of families but provide little or no help to low- and middle-income households.

I bring up this specific part of the tax code because it’s good to show us a few things: the first is that several elements of the tax code—especially the SALT cap—and the discussions around them are far more complicated than I think a lot of Americans realize. I didn’t know prior to working on this piece that support for the SALT cap is not cleanly split down party lines and that it is an incredibly contentious piece of legislation. Implementing it thereby also made it incredibly complex to reform or repeal.

The second thing is that none of you on my TikTok For You Page are actually experts at understanding the economy. This was one of the most frequently discussed parts of the TCJA and therefore one of the easiest parts of it I could explain, and this section has actively taken me so fucking long to research and write. I’m not going to say my dad was right and that I should have taken an economics class because I don’t think we need to make so many parts of our economy this impossible for the average American to understand.

The key thing that I’ve taken away from all of this research—and I want to be clear that I by no means feel I understand our system of taxation any better than I did before starting—is that while the TCJA did not have a net negative impact on the American economy in 2017, it did not have a drastically positive impact on the majority of Americans. Worse still, Trump’s “new plans” that the Republican majorities in the House and Senate can pass will likely undo the majority of positives for anyone making less than $308,900 in income each year, aside from the increase in the standard deduction.

Now that we’re talking about Trump’s economic policies: what in the fuck is a tariff?

In the most simple formal terms I was able to find:

Tariffs are taxes imposed by one country on goods imported from another country. Tariffs are trade barriers that raise prices, reduce available quantities of goods and services for US businesses and consumers, and create an economic burden on foreign exporters…

While tariffs are often described as a tax on foreign businesses and do place an economic burden on foreign exporters, the costs are often borne by consumers in the country that is imposing them. Tariffs directly increase the cost of domestic sales by artificially increasing the price on imports.

The distributional effects (the economic burden it places on households across income levels) tend to be regressive, burdening lower-income households more than higher-income households (X).

Speaking now from me to you, girlie to girlie, a tariff is a tax that is meant to encourage domestic production by creating an economic burden on importing that same item. The tax is placed on the importer, not the exporter by which I mean to say China and other countries we’re imposing tariffs on are not going to pay for them—American consumers are.

According to the Wall Street Journal,

Trump has proposed a universal tariff of 10% to 20% on all imports to the U.S. and a 60% or more tariff on goods from China. Somewhat confusingly, Trump has also separately threatened 25% tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico and an additional 10% tariff on China over immigration and drug issues.

So while the ultimate shape of tariff policy under Trump’s second administration remains unclear, it seems likely that tariffs will be more punitive and wide-ranging than the previous round of Trump-era tariffs, which started in 2018 and were focused on China. Retailers diversified their supplier base as a result: China accounted for 26% of U.S. textile and apparel imports last year, down from 37% in 2017. Much of that has shifted to Vietnam, India and Bangladesh.

The piece goes on to compare these new tariff plans to the ones Trump imposed during his first administration and explains that “contrary to what Trump contends, exporters didn’t bear those costs: A study from the U.S. International Trade Commission concluded that the cost of the 2018-2019 tariffs was borne entirely by the U.S. importers.”

Don’t worry! During his interview on Meet the Press yesterday, Trump said that “he disagrees with economists who say that ultimately consumers pay the price of tariffs.”

But when asked asked by host Kristen Welker to "guarantee American families won't pay more," the president-elect responded "I can't guarantee anything. I can't guarantee tomorrow" (X).

It does seem like Trump does not understand how tariffs work but, in fairness, even if he did understand what they are—as we all now do—it seems as though tariffs have always been finicky throughout American history. As a CBS News article explained:

Tariffs have been part of international trade since our country was founded; the first one was imposed by George Washington! And what we've learned from history is that they often have unintended consequences.

We have a tariff on sugar that has doubled the price of sugar. It has helped out our sugar cane farmers in Louisiana and Florida, but it's also driven 34% of American chocolate and candy manufacturing (and jobs) out of the country…

Tariffs against one particular country can backfire. [Dartmouth economics professor Doug] Irwin said, "With the China tariffs, we're importing a lot more from Vietnam, we're importing a lot more from Malaysia. If the idea with the tariff was to bring jobs back home, instead we're just shifting them from China to Vietnam, in some sense."

And yet, imposing tariffs seems to be an incredibly important policy for Trump to implement during his next administration. It’s almost more than an economic plan for him at this point—he truly just cannot get enough tariff:

"The word 'tariff' is the most beautiful word in the dictionary," he has said. "I think it's more beautiful than 'love.' … I love tariffs! … Music to my ears!" (X)4

Ok, enough of this. Since so many people voted for him because of it, what is Trump’s plan for the economy outside of renewing the TCJA policies and his tariff proposal?

That’s such a great question—thank you so much for asking!

I wish I had a clear answer for you all but beyond what we discussed a few sections ago, I’m not exactly sure what is actually part of his plan and what is something he just “floated” at a rally.

The best I can offer you is a summary of Trump’s proposals published in a piece from The Economist back in October which featured a mix of some things we covered and some “concepts of plans”:

Mr Trump, unsurprisingly, hopes to keep many of his original cuts in place. These include: reductions to most individual income-tax rates; a doubling of the exemption on estate taxes paid after death; and rules that make it easier for businesses to expense more investments. Simply enacting these extensions would cost the federal government about $4.6 [trillion] in lost revenue over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan scorekeeper.

This would just be the starting point for Mr Trump. As the election has turned more competitive, he has pledged more tax cuts. In 2017 he slashed the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. Now, he wants to take it even lower, perhaps to 15%. Another promise is to exempt employees such as waiters from taxes on tips. Mr Trump has also said that he would make Social Security benefits tax-free in order to help retirees. And he has promised to reverse one measure from his 2017 law: he would let residents of high-tax states resume deducting more of their local taxes from their federal tax bills.

Added together Mr Trump’s tax platform is eye-wateringly expensive, running to as high as $10 [trillion] over the next decade, according to Andrew Lautz of the Bipartisan Policy Center, a think-tank. Mr Trump has proposed some offsets, including higher tariffs and scrapping the Biden administration’s green-energy tax credits. These would be insufficient to plug the fiscal holes, however, meaning that the federal deficit—already expected to reach about 6% of GDP—may expand to 8% or so under Mr Trump.

Most importantly, there is one policy that Trump and his team really seem eager to implement. Not only could it actually be a big fucking problem for the economy, it is something Trump does have authority over.

Trump and his supporters really hate immigrants—we’ve been over this—and more than any other policy he’s set forth, his plan for mass deportations of undocumented immigrants seems to be the primary one he focused on implementing. Over the course of his first term, his administration deported 1.5 million individuals; according to The Guardian, “it’s now suggested he’ll remove 1 million a year in his second term.”

A memo from the American Civil Liberties Union earlier this year laid out the mechanics of a mass deportation. Trump would need to arrest millions of people, put them into removal proceedings before judges, litigate those cases including appeals and then actually remove them – a herculean task with constitutional and statutory requirements at each step.

“No part of it has ever operated at anything approaching the scale and speed that Trump’s plan requires,” the organization wrote. “There can be no doubt that Trump would attempt to defy constitutional and other legal protections in service of his draconian goal” (X).

While the exact number of undocumented immigrants living in the US differed between the sources I found, the number is estimated to be between 11 and 14 million individuals. Further, a report published by the American Immigration Council back in October explained how

a one-time mass deportation operation that would remove 13.3 million immigrants without legal status would cost at least $315 billion. If the U.S. government were to instead invest in expanding the current infrastructure to a point where it could arrest, detain, process, and deport one million people a year, we estimate this would average out to $88 billion annually, for a total cost of $967.9 billion over the course of more than a decade.

Notably, even if the government were to successfully increase deportations to one million per year, it would take over ten years to arrest, detain, process, and remove all 13.3 million targeted immigrants in the U.S. today, even presuming 20 percent left voluntarily. The U.S. government would have to build and maintain 24 times more ICE detention capacity than currently exists, including potentially thousands of new “soft-sided” detention camps. The government would also be required to establish and maintain over 1,000 new immigration courtrooms to process people at such a rate…

Mass deportation would cause our GDP to shrink by 4.2 percent to 6.8 percent. By comparison, the U.S. GDP shrunk by 4.3 percent during the Great Recession between 2007 and 2009.

I want to say this is The New Border Wall and it’s never going to come to fruition, but someone who has both referred to immigrants as “people [who] are ‘poisoning the blood’ of the country” (X) and has claimed he wants to ban birthright citizenship in the past year is someone who is determined to see this plan through. Without even touching on the appalling lack of humanity required to carry out mass deportations, the economic impacts of this plan have been described across every source I found as some synonym of catastrophic.

And I mean, it makes sense: what use do we have debating the economic benefits of a SALT deduction cap when the US economy has been blown to bits? What use is it to discuss further corporate tax cuts when our country has lost a significant portion of our labor force? How many times can you save the American economy after it starts to capsize?

Is there any hope that this will not be a catastrophic dumpster fire?

I’m genuinely not sure. Because Trump has promised several policies that will have competing effects on the economy and its growth potential, there really is no clear answer for which of the proposals are actually going to be implemented before we get to his term.

I think this is where I get the most frustrated with people who justified their vote for Trump with the economy and his plans for it because I can’t stop myself from asking…what plans? Where amongst his ramblings did you find something coherent enough to be labeled “a plan”?

My gut instinct after researching and writing this piece is, candidly, to assume the worst. I’m not saying this hypothetically: we can assume that he is going to do everything in his power to get his supporters in Congress to implement ridiculous tariffs and his government agencies to launch a mass deportation campaign, not simply because he promised it on the campaign trail but because he’s already hired people who very much want to get both policies enacted.

But while we won’t know Trump’s exact economic plan until next year and truthfully, I don’t know if he will either, I feel like I’ve walked away from this piece confidently able to say that I don’t believe anyone who says they voted for him because he’d build a better economy and I’m glad I didn’t take an economics course in college. If I had, I wouldn’t have been able to write this unnecessarily long and exasperated piece for you all today.

By the way, I also learned what a recession is for this piece and wanted to explain it in case no one has ever explained it to you. Whereas inflation pertains to the increase in prices specifically of goods and services, a recession is a downward shift in the economy overall. According to Investopedia, “a recession is a significant decline in economic activity that lasts longer than a few months.” There’s more to be said about recessions but I’m not the one who should be saying them…at least not today.

THIS HASN’T HAPPENED TO ME!!!!!! But it is a big fear of mine!!!!! Just because I’m learning about the economy doesn’t mean I’m any better at math!!!!

I’m talking about me making a Target purchase regardless of inflation prices. I will never not make a Target purchase if I need something from Target—that’s just showbiz, baby!

Something to note about why Trump might love tariffs so much is that while they still technically need to be passed by Congress, the Trump tariffs Wikipedia page reads that, “In 1977, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act shifted powers even more towards the White House. The Trump administration claims that it gives the President the authority to raise tariffs without any limits during a national emergency of any kind. Legal scholars disagree because the IEEPA does not mention tariffs at all and transfers no authority of tariffs towards the President,” but it’s just something to keep in mind this time around.