If God is a Woman, She's Definitely a 'Pick Me' Girl

Looking at the recent violence against women in Atlanta, the U.K., and the goddamn House of Representatives

Last Tuesday, a gunman targeted three spas in Atlanta and killed eight individuals, including seven women, six of whom were Asian.

Regardless of how the gunman himself defines it (and we don’t even have time to unpack all of that fuckery), this was a racialized hate crime. A white man targeted Asian-owned businesses with the intent to murder. That is the definition of a hate crime.1

But I want to focus on one component of these attacks that fits into a couple of other conversations we’ve been starting to have over the last few weeks. We cannot overlook the gendered nature of this attack: the gunman revealed the sexual nature of his motive and how it was his attempt at eliminating his “temptations.” He targeted Asian women specifically due to how we as Americans have historically been taught to see Asian women.

This attack came one week after the world learned of Sarah Everard’s name and story, and less than 24 hours before the House held a vote on renewing the Violence Against Women Act in which 172 Republican representatives voted against renewing the act.

This week’s newsletter will probably not be as funny as the others have been because today, we will be breaking down these three events, what the reactions to each have been, and how we can actually start making a change to protect women across the world (hint: it’s not women who have to make the changes).2

How America Has Failed Asian Women

One of the first things I remember learning in my English classes was the literary device of tropes, and that tropes are used to make characters in different stories familiar to all kinds of readers. You may not understand the world of Ancient Greece but you can recognize that Odysseus is the hero swooping in to save the day (and no, I have never warmed up to The Odyssey, thank you).

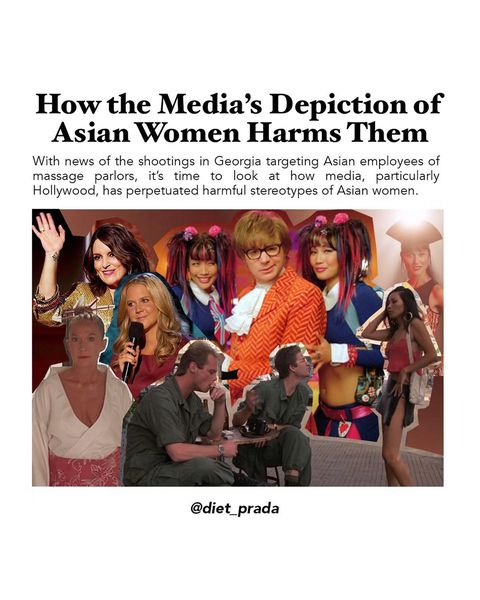

Our laws and history have created a trope for Asian women that has been unending damaging. There are so many disgusting and pervy names for this trope so to not give them any more air, we’ll refer to it here as “hypersexual objects.”

This trope began with the Page Act of 1875 which was the first restrictive American immigration law on the books. The law loosely banned any immigrant from East Asia from entering the U.S. to be a forced laborer, a prostitute, or if they were considered a criminal in their home country. However,

“Legislated amid the spread of anti-Chinese fervor from the west coast to the rest of the United States, this law was an early effort to restrict Asian immigration without categorically restricting Asian immigration on the basis of race and instead restricted select categories of persons whose labor was perceived as immoral or coerced.” (x)

The law was most heavily used against East Asian women attempting to immigrate to America, with Chinese women, in particular, facing a difficult time. And by difficult time, I do mean that President Ulysses S. Grant said during the Seventh Annual Message to the United States Senate and House of Representatives, that we need to get a handle on the polygamists in Utah, “while this is being done I invite the attention of Congress to another, though perhaps no less an evil— the importation of Chinese women, but few of whom are brought to our shores to pursue honorable or useful occupations.”3

Because the Page Act became known for banning Chinese prostitutes, the obvious logic for brilliant olden day Americans was that all Asian women were prostitutes.4 Ellen Wu, a history professor at Indiana University, told ABC News that “‘as early as the 1870s, white Americans were already making this association, this assumption of Asian women being walking sex objects…’ Asian lives are seen as ‘interchangeable and disposable… They are objectified, seen as less than human. That helps us understand violence toward Asian women like we saw this week.’”

This stereotype of Asian women as hypersexual objects was then coupled with what journalist Sara Li writes is the “‘submissive’ trope, stemming from the days when colonial soldiers would invade Asian territories and sexually prey upon the women there.” In her recent Cosmopolitan article, Li includes a study done by National Network to End Domestic Violence which “showed that Asian women are more likely to experience sexual violence by an intimate partner than any other ethnic group.”

All of this history comes together to form distinct yet connected mentalities: the first is that Asian women are fetishized for their presumed hypersexual yet submissive personas; this then leads to a desire for female Asian sex workers; and finally, the degradation and the fetishization culminate in various justifications for violence against female Asian sex workers and for violence against all Asian women.

The conversations around sex work and around migrant survival sex work, in particular, are really complex and deserve their own newsletter rather than just space in this one. And, while there is no confirmation that any of those murdered were sex workers, we can’t let that fact stigmatize sex work further because the victims were targeted for their presumed professions.

What we need to note is that no one’s race, gender, or job should make them deserving of murder. The proliferation of harmful tropes about Asian women as well as our nation’s paradoxical relationship with sex work is what led to the attacks in Atlanta and what will likely continue to lead to more crimes against Asian women until we learn how to face our historical mistakes and our fake ass moral quandary that leaves sex workers remarkably vulnerable.

The names of those killed last Tuesday are Xiaojie Tan, Delaina Yaun, Paul Andre Michels, Daoyou Feng, Yong Ae Yue, Hyun Jung Grant, Soon Chung Park, and Suncha Kim.

What Happened to Sarah Everard?

On March 3 of this year, Sarah Everard was walking home from a friend’s house in Clapham to Brixton. She walked on brightly lit streets not too late at night, she called her boyfriend to let him know where she was, she wore sensible shoes for running if necessary, and she was murdered.

Sarah’s story highlights that even when women do everything “right” to protect ourselves, we literally can never be safe. Her story is prompting people everywhere to have a number of conversations, some productive and some… certainly less so.

One of the things her story has revealed is while violence can happen to any woman or femme, it is far less commonly discussed when it occurs to women of color, as discussed here in Al Jazeera, in the above section, and in this Full Frontal with Samantha Bee clip. The shared commonality of violence (and it fucking sucks to say this) seems to have opened a dialogue that previously went under-discussed:

“For many women in Britain, Ms. Everard’s killing and the police’s violent dispersal of a London vigil in her memory have triggered a similar horror, on a less dystopian scale, about how unprotected they truly are. It has become a moment, too, to reflect on the suffering of women of color, and other groups targeted for abuse, that has long been ignored.” (x)

That New York Times article referenced a little snippet of commentary on what happened at a vigil held in Everard’s honor. This actually leads into one of those less productive conversations: the Metropolitan Police has come under fire in the last week, first because of how they handled enforcing COVID safety protocols at the vigil held in Clapham Common where Everard was last seen.

Secondly, the British government announced that in response to Everard’s murder, they would install

more CCTV cameras, better street lighting, and plainclothes police in bars and clubs to watch for attacks on female patrons. And it campaigned for more support for the police and crime bill, which would grant sweeping new powers to police departments across the country.

What women want is not a larger police presence because, seeing as Sarah Everard’s kidnapper and murder was a police officer, that does not inherently mean more support or stronger protection of women. What we want is to not have to be responsible for not getting kidnapped, murdered, attacked, catcalled, harassed, upskirted, violated, or made to feel unsafe just by existing. We want men to be held accountable for their violence against us so that maybe we don’t have to perpetually walk through the world with our keys between our fingers.

I Have Had it With This Motherfucking House in This Motherfucking Congress

Now, if you’ve been reading this far and you have a reasonable head on your shoulders, you might be thinking, “Hey, is there a law literally called the Violence Against Women Act? Wouldn’t that help for something?” There is!! And maybe!!! If nasty partisanship wasn’t involved!!!!

Last week, the House held a vote to renew and update the VAWA (and by the way, yes I do know that President Biden sponsored the bill back when he was a senator but read the room. I’m not in the mood to pat men on the back today):

The new VAWA would expand protections from women to LBGTQIA Americans. It grants tribal courts authority to prosecute non-indigenous people for offenses like sex trafficking, an attempt to address an epidemic of violence against indigenous women. And there is the closing of the “boyfriend loophole,” which would prohibit anyone convicted of stalking from buying a firearm, which has made the bill the target of the NRA and NRA-friendly legislators. (x)

This is the part that made 172 Republican representatives vote “No” on Wednesday. Fucking guns?!!?!?!?!?!? One woman who has made it clear she does not support other women, Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), went so far as to say, “‘If you want to protect women, make sure women are gun owners and know how to defend themselves… That’s the greatest defense for women.’” (Fun fact: that’s how MTG says “Happy Women’s History Month!!”)

The fact that there is always a partisan sticking point —even for domestic abuse survivors like Senator Joni Ernst (R-IA) who objects to VAWA because of the boyfriend loophole— is why women don’t feel safe. The fact that the British government’s idea of how to make women safer after a violent attack by a police officer is to increase police and surveillance presence is why women don’t feel safe. The fact that Asian women are targeted and fetishized for a trope cast onto them is why women don’t feel safe.

We need to stop misunderstanding violence against women, we need to stop telling women how to make themselves safer in the face of attacks on them, and we need to stop focusing on the wrong parts of this conversation.

So What Can Men Do To Help?

Be open to being held accountable.

One of the most widespread charges against women holding leadership roles is that they’re too emotional and too sensitive.

Anger is an emotion. Lashing out at a woman trying to help her world safer and you become a more empathetic person is too emotional of a reaction.

Fear is an emotion. Being too scared of getting corrected or told you’ve messed up so you never have hard conversations is too emotional of a reaction.

You’re not any better than your effort in growing. You’re not too good to grow.

Hold your friends accountable.

First of all, rape jokes are not and have never been funny. If your defense of your friend is that he was just joking around, neither of you have a sense of humor.

Call out harmful comments when your friends or family or general male peers make them. Oh, why not? Too scared they’re going to call you a little girl for not taking a joke? Hm. Wonder where they got that.

Stop supporting artists that harm women. Stop giving them your money. Find out how your elected officials vote and if they vote against women’s safety, vote against them.

✨Unfriend your friends that actively harm women. They’re not good friends because they’re not good people. They’re criminals.✨

Listen to women.

Don’t force your female friends to talk to you about their traumas and hardships, but when they do feel safe enough to open up to you, make sure you actually hear what they’re saying. Don’t write them off. Don’t belittle them. Don’t question what they’re telling you has happened to them.

While the reports I could find on false reporting of sexual violence seems a tad dated (2010 and 2012) and both contain data that is not broken down by gender, if your first reaction to a woman telling you about an assault is that she’s lying, you’re in the wrong fucking place.

There are so many more things to do and so many other ways to be supportive of women. We’re all learning how to be better in our own various ways. No one will be perfect, but no one should be actively harmful either.

Not a fun sidebar, but under Georgia’s hate crime bill, judges are allowed to impose “sentences to increase punishment against those who target victims based on perceived race, color, religion, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender, mental disability, or physical disability.” Saying it wasn’t a racial crime because it was a sex crime really doesn’t matter because hate is hate. Literally, even Brian Kemp knows that.

I want to note that since this newsletter primarily focuses on attacks on cisgender women, that will largely be the focus of today’s piece. This is by no means taking away from hate crimes and violence against trans and gender-nonconforming individuals, but that conversation deserves its own focused newsletter.

Earlier in the speech he asked to “invite [Congress’s] attention to the necessity of regulating by law the status of American women who may marry foreigners” as a way of handling the issue of fraudulent naturalization and expatriation which seems very nationalistic and playfully xenophobic

This article from Kerry Abrams in the Columbia Law Review discusses how “when Congress banned the immigration of Chinese prostitutes with the Page Law of 1875, it was the first restrictive federal immigration statute. Yet most scholarship treats the passage of the Page Law as a relatively unimportant event, viewing the later Chinese Exclusion Act as the crucial landmark in the federalization of immigration law. This Article argues that the Page Law was not a minor statute targeting a narrow class of criminals, but rather an attempt to prevent Chinese women in general from immigrating to the United States.”