Your twenties are often regarded as a time for making mistakes and figuring out how you want to live your life. While some people might date the wrong person or say something dumb after drinking too much, I decided to read the Constitution, annotate it, and write an entire piece analyzing it.

For a document that governs so much of American life and is so regularly discussed (especially as of late), I’m going to go out on a limb here and say the majority of people reading this newsletter right now have not read the Constitution in its entirety in at least the last ten years. That’s not a read—it is an observation I’ve filed away in my larger beef with American democracy regarding the fact that so few of us actually know how our government operates. In many ways, that beef is the governing principle of this very newsletter.

In any case, experts have started arguing that we are approaching a constitutional crisis under the second Trump Administration. More to it, the Constitution has been challenged, questioned, or outright violated so many times in the last two months alone that I thought it would be a good idea to review it from start to finish and share my thoughts with all of you.

I feel like conservatives and MAGA subscribers in particular have glomped onto this idea that they are the defenders of the Constitution, and they’re right, to a degree. There are a lot of parts of the Constitution that are really fucking stupid, dated, or racist, just as there are parts of it that are progressive and essential to the function of democracy. The problem is you can’t have one without the other. For the Constitution to work, we have to accept that the shitty aspects of it are entwinned with the parts that give us the freedom to do things like call it shitty.

It’s not an ideal arrangement by any means, and I want to make that clear before I start sounding too if you don’t like it, you can leave. But it also makes the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. CASA, Inc. last week all the more troubling, as it opens the door to questioning and revising explicit wording of the Constitution on a partisan basis.

We’re going to get into it all. Today, we’re going to talk about what the Constitution says, what it all means, and what challenges it’s currently facing. It’s a conversation so chaotic and messy, mainly because I went into writing this without an outline and with a bad attitude. That said, I’m going to do my best to give an overview and some analysis that makes sense to me without boring, confusing, or pissing anyone off.

But before we begin, I just want to say, from the bottom of my heart:

They Always Ask, “What is the Constitution?” But Never, “How is the Constitution?”

Let’s start with the basics because I fear we’ve lost the plot a bit when it comes to talking about the Constitution. To start, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are like eyebrows: sisters but not twins.1 The Declaration was signed on July 4, 1776, and declared the United States free from British colonial rule, thereby establishing it as a sovereign country. The Constitution was crafted and ratified after the US had won the Revolutionary War, and it allegedly still serves as the governing text for America today.

The Constitution is made up of three parts: the Preamble, the Articles, and the Amendments. The Preamble is the iconic part that begins with the lines, “We the people,” and the first ten amendments are referred to as the Bill of Rights. In all, there are seven articles and 27 amendments in the Constitution, with the last one ratified in 1992.2

The seven articles of the Constitution are the foundation of the document, describing how the Founding Fathers envisioned the roles of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, as well as how statehood and citizenship would be determined, how amendments would be added, and how the text was meant to be interpreted.

The 27 amendments cover everything from whether or not you have to allow soldiers to live in your home during peacetime (you don’t) to presidential term limits (two, for now) to who gets to vote (everyone 18 years and older, without the restriction of poll taxes). There are literally two amendments that address each other—the 18th Amendment, which started Prohibition, and the 21st Amendment, which ended Prohibition. And somewhere in the middle of those two, women got the right to vote.

Some of the amendments change the base wording of the articles. For example, the 17th Amendment altered Article I, Section 3, which initially gave state legislatures the power to elect their Senators. Ratified in 1913, the 17th Amendment gave that power to the people after the majority of states at the time had adopted the Oregon System, “under which state legislative candidates were required to state on the ballot whether they would abide by the results of a formally non-binding direct election for U.S. Senator” (X).3

Some of the amendments change a whole lot of everything altogether. We talk a lot about the Reconstruction Amendments—the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, specifically—which addressed slavery, citizenship, and voting rights following the Civil War, for good reason. Of course, these additions were not without their controversies (I mean…the 13th Amendment…diva), but I think we often focus on the progress America made by ratifying them without always acknowledging the problems woven throughout the original text. Bear with me: I’ll unpack what I mean more on this in the next section on constitutional controversies (gasp).

Before we move into some of the problems with and challenges to the Constitution, I wanted to look more at certain protections, clauses, and amendments that I think are worth highlighting. Like we all know about That Girl, the 1st Amendment, but what do you know about the 20th Amendment? She’s the reason why new presidents and vice presidents are sworn in on January 20th following their election, and why Congress commences its new sessions every January 3rd. Apparently

the cycle of beginning sessions in January, with the first session of each Congress starting shortly after the election, and of ending sessions late in the year, seemed so natural that perhaps only historians remember that it only began in 1935 with the implementation of the 20th Amendment (X).

Perhaps the only thing that I love about the Constitution with certainty and no stipulations is that even its most mundane aspects are the result of some drama.

Take the 11th Amendment: it was introduced and ratified in response to the Supreme Court’s reading of the wording in Article III, Section 2. The argument that Federalists (very generally—those in support of the Constitution and a centralized government) used to sway Anti-Federalists (the opposite of Federalists) was that “Article III would not be interpreted to permit a state to be sued without its consent.”

However, some other Federalists accepted that Article III permitted suits against states, arguing that it would be just for federal courts to hold states accountable.

Soon after ratification, individuals relied on this Clause in Article III to sue several states in the Supreme Court. One of these suits was Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), in which a citizen of South Carolina (Chisholm) sued Georgia for unpaid debts it incurred during the War of Independence. Georgia claimed that federal courts were not allowed to hear suits against states, and refused to appear before the Supreme Court. In 1793, the Supreme Court ruled, by a four-to-one vote, that Chisholm’s suit against Georgia could proceed in federal court. The Court relied in part on the text of Article III, explaining that “between” encompasses suits “by” and “against” a state (X).

As there were several cases like Chisholm pending around the country at the time, some people freaked the freak out and introduced the 11th Amendment to clarify who could bring suits against states, and for what. But the gag is that even though the amendment was intended to narrow interpretations of Article III, the Supreme Court’s decisions on several cases challenging its exact scope of the amendment have led to more micro-dramas than a mid-season episode of Summer House.

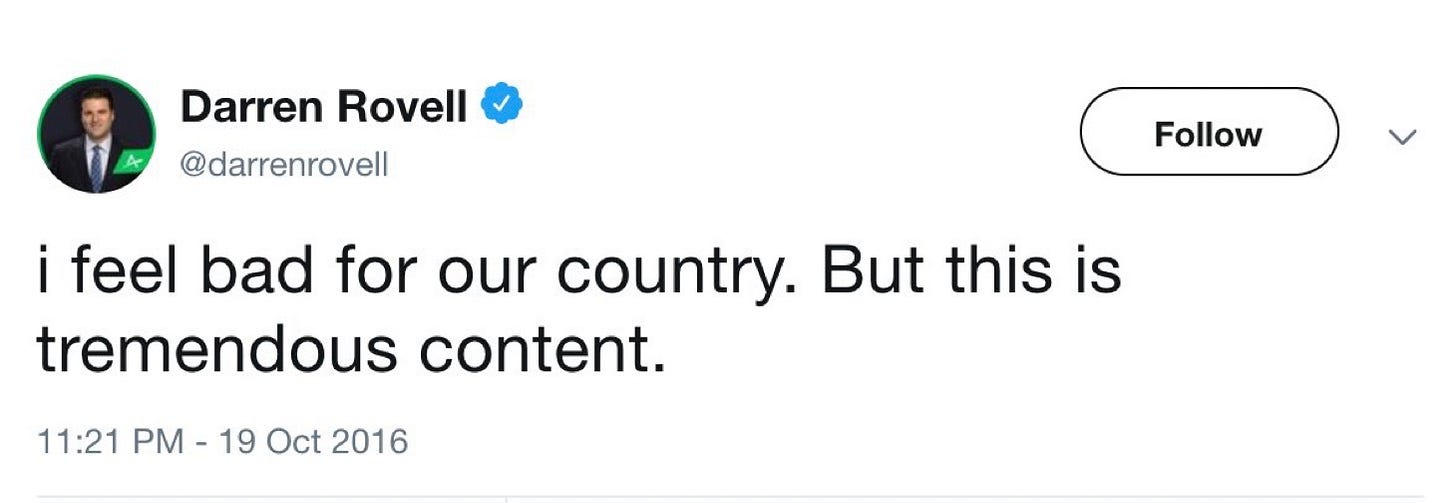

My main takeaway from reading the Constitution and the subsequent research I’ve done to write this piece is that it is a deeply unserious document written by deeply unserious people that has the existentially serious job of protecting American democracy. It is the literal embodiment of the tweet:

There are so many more #JustConstitutionThings I want to talk about and petty histories I’m dying to share, but I promised you all I wouldn’t bore you. So instead of analyzing the depths of the 9th Amendment (a new favorite of mine, to be sure), I want to talk about a long-standing controversy with and a recent challenge to the Constitution.

Controversies! Drama! Scandal!

If you are still wondering why I mentioned the problems of the original text of the Constitution while I was talking about the Reconstruction Amendments, the wait is over. Unfortunately, though, I now have to introduce you to originalism.

Originalism is a theory of interpretation of the Constitution “which bases constitutional, judicial, and statutory interpretation of text on the original understanding at the time of its adoption. Proponents of the theory object to judicial activism and other interpretations related to a living constitution framework” (X).

Jonathan Gienapp, an associate professor of history and law at Stanford University, further explained in a 2024 article that

instead of adjudicating cases based on what the Constitution has come to mean in light of evolving attitudes, values, and conditions, or longstanding precedents and practices, originalism calls for judges to enforce the meaning the Constitution had when it was laid down. More often than not, this backward-looking exercise focuses on the nation’s eighteenth-century founding, the period when the United States earned its political independence and adopted the national constitution that remains its fundamental law to this day.

For several decades, originalism has been the rallying cry of the conservative legal movement, and thanks to the recent vicissitudes [a change of circumstances or fortune, typically one that is unwelcome or unpleasant] of American politics, it now dominates the federal judiciary, for the first time ever commanding a majority on the Supreme Court.

Originalism is bizarre to me for several reasons that we don’t have time to fully get into. But I do want to lay out my major case against taking a text from 1787 at its literal word. In the original text of the Constitution (which many originalists regard only as the Preamble, the Articles, and the Bill of Rights), Article I, Section 2 states that

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 elaborates that

the Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

And Article V of the original text reads, in part, that

no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

Now, not to go all originalist on you, but the word slavery never appears explicitly in the original text. Yet, the Framers found three different ways to talk about it and, more insidiously, enshrine protections for it in the Constitution.

Of course, it’s important to note that “there is a settled meaning of [Clause 1 in Article I, Section 9]: it is no longer relevant in the same sense, for example, that the First Amendment is still constitutionally relevant” (X). And yet,

although constitutionally inoperative for over 200 years, still remains there for all to see and read. It is in the Constitution. And so the Clause, in a larger sense, has a continuing cultural and political constitutional relevance in the discourse of the morality and profitability of the international trade in human beings. People rightfully wonder today, and earlier, why is such a Clause there in the first place and to whom does it refer? We do know the Framers are talking about the slave trade, right? How attentive should we be to the specific language of the Clause or does the language actually inform us about what is trying to be conveyed? And why is this Clause the opening clause of Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution? (X)

What I’m trying to get at here is that some aspects of the original text of the Constitution were unequivocally bad and wrong. While an originalist lens might be a valid way to understand the text and, to a degree, answer some of those questions posed above, it should not be how our Supreme Court decides modern matters. More to it, it’s not how the Supreme Court decides modern matters when its originalist members disagree with the text.

That is because Supreme Courts have always—in their own special, fucked up ways—been reflective of the politics of the nation at their time. Despite the grandeur they command from being the country’s top court, they are made up of people with political affiliations that determine how they view cases and make decisions. And this court, at this time, is reflective of the hard shift to the right we’ve been seeing as well as the political extremism defining our national politics.

Let’s apply all this to the current debate over birthright citizenship. First and foremost, birthright citizenship is still a constitutionally protected right under the 14th Amendment, which reads, in part,

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

One of Trump’s first executive orders on Inauguration Day claimed that instead of offering citizenship to those born in the US or those who have become naturalized citizens, the Amendment actually

has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to everyone born within the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment has always excluded from birthright citizenship persons who were born in the United States but not “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” Consistent with this understanding, the Congress has further specified through legislation that “a person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” is a national and citizen of the United States at birth, 8 U.S.C. 1401, generally mirroring the Fourteenth Amendment’s text (X).

The order goes on to say that anyone born in the US whose parents were not both citizens at the time of their birth cannot claim citizenship, which is patently not true. As a result, federal judges ordered injunctions, meaning the executive order could not take effect across the country. However, on Friday, in Trump v. CASA, Inc., SCOTUS ruled that “nationwide injunctions by lower courts ‘likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has given to federal courts,’ unless it is required for complete relief for parties in any given case” (X).

What that means is that

the justices did not rule on the constitutionality of the executive order issued by Mr. Trump in January, which seeks to end the practice of automatically granting citizenship to anyone born in the United States, even if the parents are not citizens. That question is likely to come back to the Supreme Court, perhaps as soon as next year.

In the meantime, the decision cleared the way for the executive order to go into effect in the 28 states that have not challenged it, which could create a patchwork system in which the rules for citizenship are different in different parts of the country (X).

In other words, “the practical effect of Friday’s 6-3 decision is that, in 30 days, birthright citizenship would end in the 28 states that have not challenged Mr. Trump’s order,” as the New York Times explained.

Of course, I cannot emphasize enough, SCOTUS has yet to rule whether or not Trump’s executive order—which explicitly violates the 14th Amendment—violates the 14th Amendment. But it would not be a stretch to imagine a court so often split 6-3 on ideological lines ruling that the order is more constitutional than the literal amendment because birthright citizenship wasn’t guaranteed in the “original text.” It’s funny, though, because you know what else wasn’t guaranteed in the original text? The basis for originalism.

And would you look at that—I found a way to talk about the depths of the 9th Amendment!

Hope Is a Dangerous Thing For a Woman Like Me to Have…And I’m Honestly Not Sure I Have It

I would be remiss not to mention that in addition to the constitutional challenges the Trump Administration has been teeing up in literal court, there have also been several taking shape in the court of public opinion.

On May 20, Kristi Noem and her injectables stated during a Senate hearing that “habeas corpus was the ‘right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country’” (X). Notably, habeas corpus (Article I, Section 9, Clause 2) is the “constitutional right that ensures that people have a chance to challenge their imprisonment in front of a judge. Habeas corpus ensures that the government cannot detain someone without a lawful basis” (X).

Additionally, Trump’s deputy chief of staff and noted white nationalist, Stephen Miller, reportedly said:

“The right of ‘due process’ is to protect citizens from their government, not to protect foreign trespassers from removal. Due process guarantees the rights of a criminal defendant facing prosecution, not an illegal alien facing deportation” (X).

Due process is protected explicitly in both the 5th and 14th Amendments, and there is legal precedent written by one of the most famous originalists, Justice Antonin Scalia, affirming that “‘it is well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings’” (X).4

What these two med spa freaks are doing is using the Constitution’s credibility to make their cases, but misrepresenting what the Constitution actually says. While this is not nearly as dangerous as what will be decided by the Supreme Court in the coming years, they can still convince people that what they’re saying has some constitutional basis and therefore validity. More to it, with the decision in CASA, Inc., SCOTUS has restricted the checks and balances the judiciary has on the executive branch…which means executive employees like Noem and Miller may eventually gain more sway over public policy as federal courts lose the ability to regulate their actions.

David Gans, a director at the Constitutional Accountability Center, has spoken about the increasing potential for a constitutional crisis, either due to “overreach by government powers beyond constitutional limits” (such as by Noem’s Department of Homeland Security or Miller’s army of aggrieved demons), or to “conflicting interpretations of the Constitution” (see: both sections above).

But he also made a really important point:

Gans said current times necessitate more education on the government and systems that define U.S. democracy.

“We’re in a period of conflict and struggle over our constitutional system, and the question is not only for lawyers and for courts, but for everyone…All people have an important say in this fight over the meaning, the enforcement, whether our constitutional promises will stand firm” (X).

The one section of the Constitution we have not discussed at length today is the Preamble, which is only 52 words long and starts with the declaration, “We the People.”

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Given everything we’ve discussed today, it feels like this is the most important part of the Constitution. We should not take for granted the fact that, regardless of what the subsequent text says, regardless of what it has gotten and sometimes continues to get horrifyingly wrong, there is this idea that we can keep improving. There is a more perfect union to form, with protection and tranquility and justice for all of us, if we just keep going.

And yeah, maybe that’s a naive lens to view the Constitution through, but I’d prefer that over some bullshit originalistic take any day.

Thank you for reading!!! Thank you to my brilliant friend Hallie for her legal insight!!! Stay tuned for next week’s piece where E4P’s in-house, not-yet-barred lawyer Skylar Corby returns to break down another tumultuous SCOTUS term!!!

PLEASE READ THE CONSTITUTION!!!!! Please know your rights!!!! Don’t listen to Kristi Noem’s two-syringe lips or Stephen Miller’s active absence of them—your rights are afforded to you by the Constitution and are inalienable regardless of your immigration status!!!!!!

According to the National Constitution Center,

most Americans lack even a minimal historical understanding of [the Constitution]…In one recent survey, for example, 71 percent of Americans believed that the phrase “all men are created equal” appeared in the Constitution, not in the Declaration of the Independence…(X)

While they don’t cite this survey, I was able to find a piece from the local St. Louis branch of NPR from 2013 that references the 71% statistic.

While we don’t have time to go through all aspects of the text line by line, I cannot emphasize how easy it is for all of us to read and, maybe more importantly to some, how easy it is to find reputable resources to help make the language more digestible.

Basically, the majority of state legislatures were electing Senators based on the popular vote, so the 17th Amendment just made it common practice.

Not the ideal wording there, but we take what we can get…especially from Scalia.