Economics For Dummies

Alternatively: Economics for Students Who Were a Pleasure to Have in Class

Honestly, there’s kind of no way to top the opening of the last E4P installment featuring my dad so I’m not even going to try.

Without further ado or fanfare (just as he prefers), I’m happy to share that Emily For President’s resident economist Bill Sharp has returned, this time to explain what the current job market looks like, what that means for the economy overall, and what in the heck is an exogenous shock.

Make the Economy Make Sense for the First Time Again

Maybe this is a personal thing but lately, I’ve felt there have been so many conflicting pieces of economic news—we’re nearing a recession, mass layoffs, record-low unemployment numbers, more mass layoffs, inflation is growing, inflation is shrinking, the economy is booming, are we nearing a recession?, whose fault is the recession?, is a recession right for you?—that I have come to believe we are intentionally being bamboozled. I know I’m not the world’s greatest mathematical mind but certainly, I shouldn’t be this confused.

To get to the bottom of things and to hopefully make some sense of everything, I asked my dad:

Emily: How would you describe the current state of the economy in five sentences or less from your perspective?

Bill: The economy is doing very well. I don’t see any signs of a recession on the horizon in the next three to six months. There was inflation, which was very high and accelerating, is now less high and decelerating, so we’re experiencing disinflation right now. Still very high on a historical basis relative to the last 30 years, but it’s getting better.

Emily: Do you think we are nearing a recession?

Bill: No. Remember when we went to the cookout on Memorial Day and everyone was saying we were in a recession, because that was what they were hearing in the news and all that, and I said, “No, I don’t see signs of it.” To this point, I don’t see signs of it. There are some sectors of the economy that aren’t doing so well, like the housing sector, but is the economy is in a recession? I’d say no.

Last year, we had two quarters of negative growth. The rule of thumb is when that happens, you’re in a recession. That’s not always the case—that was the exception.The underlying trend in GDP was still on the positive side. It was special factors that brought it down. And right now, we’re still growing and I don’t see it turning down in the first half of this year either.

Emily: I don’t know if you know exactly why then, but why do you feel a lot of people are talking as if we’re nearing a recession?

Bill: Because the people in my profession are always trying to be the first to say it, so they’re always going to say it but they’re not held accountable. They can say it, and they can say it, and they can say it, and eventually, they’ll be right. But if you say it nine times and you’re wrong eight, you can’t say, “Aw, I was right” because you were still wrong eight of the nine times.

Emily: You said the rule of thumb marking when we are in a recession wasn’t necessarily true this time. When is your rule of thumb of when you would know something was happening with the economy, we’d be in a recession? Is there a single marker for that for you?

Bill: For me? Yes, it’s the labor market, and the labor market showing quite a bit of weakness. People losing jobs, unemployment going up. That is not the case in the aggregate. There are always people losing jobs, being out of work. That’s always going to be the case but at the same time, there are always going to be people being hired. So even during recessions, there’s hiring taking place but just that the amount of job losses is greater than the hiring so on net, job losses are occurring.

As someone who has been incredibly active in the job market for the past three months with little success, it has felt a little disorienting to hear that unemployment numbers have hit historic lows. My lived experience is all-encompassing because, very obviously, it is mine, but because the economy, as my father is wont to tell me every chance he gets, is an aggregate and does not revolve around me, I asked:

Emily: What are your thoughts on the current state of the job market in the US?

Bill: Extremely tight. Extremely. Tight.

Emily: What do you mean by that?

Bill: In my thirty-plus years of doing this, it is probably the strongest labor market I’ve ever seen.

Emily: Why?

Bill: Unemployment is very low.

Emily: In this household, it’s not.

Bill: Your personal experience is not always representative of the economy as a whole. So yes, there are always certain people, certain sectors, groups, and industries, that aren’t going to do as well as others but right now, the job market is very tight.

Emily: Historically, when have we seen record-low unemployment numbers like this, or a job market that has looked like this? What did that mean for the economy at that time?

Bill: The last time we’ve seen a labor market this tight was in the late Sixties. GDP was growing well over 4%. I think one of the key reasons why GDP growth has been a lot lower than typical when the labor market has been this tight is I think GDP is not adequately taking into account what’s happening in the service sector of the economy so we’re underestimating GDP. That’s one of the reasons why last year, when you had the two quarters of negative growth—it wasn’t representative of the overall.

There’s a weekly report that comes out for new filings for initial claims for unemployment insurance. Up until today, we were at the lowest level since 1967, ‘68 on a couple of the measures some of the weeks, and record low for another week. Today, we ticked up a little bit but still, even though it went up, the level is still at a historical low.

Emily: When the situation was like this in the 60s, what happened as a result of it, and what shifted it off this course?

Bill: That I don’t know much detail about because I was only six years old. A lot of things that were going on at that time—I think the primary one was the Vietnam War. The Cold War. Inflation was becoming a major problem. The Oil Crisis hit, so all those things right there were what—

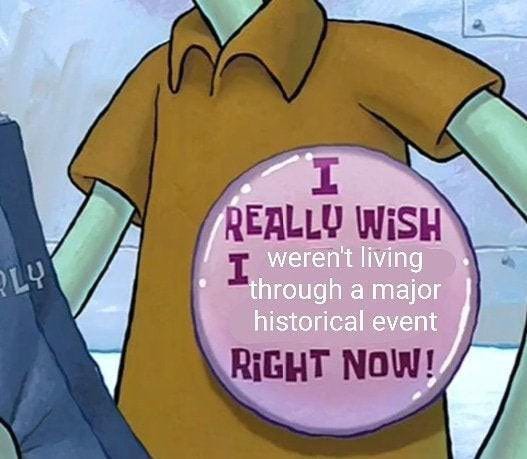

Emily: So it would take a historical event to shift where we’re heading?

Bill: Sort of like a pandemic?

Emily: I was going to say. We’re kind of living in an era of constant historical events.

Bill: We refer to those in the economic world as exogenous shocks. [He did not say exogenous correctly.]

Emily: That’s a big word.

Bill: It is for me. Exo—exog—eh, whatever.

Emily: I’ll Google it so I get the proper spelling.

Bill: E-x…e-x-a-n-g-e-o-u-s.

Emily: That is not correct.

Bill: E-x-g-a-n-o-u-s.

Emily: It is e-x-o-g-e-n-o-u-s.

Bill: Right, just as I said.

Now that I had a base understanding of where our economy currently stands and what could theoretically (in my best RuPaul voice) fuck it up, I wanted to ask my dad about the parts of this conversation I found to be in opposition with one another, namely, how can there be mass layoffs and record unemployment at the same time????

If Alix Earle Jumped Off a Cliff, Would You???

Yes, this section title may apply to only the smallest sliver of the actual content in this next part, but I have to stay relevant by whatever means necessary.1

Picking up right where we left off, I asked:

Emily: How do you reconcile the claims of record-low unemployment numbers with the almost near-constant news of mass layoffs at major companies in a variety of industries?

Bill: Mass or massive?

Emily: Mass. Did I say massive again?2 Anyway, you see with Meta, with Amazon, with Twitter, with Google, Pinterest—

Bill: Disney today.

Emily: Disney—

Bill: Microsoft. Zoom.

Emily: All of the major tech companies and also a number of media companies.

Bill: Okay.

Emily: And these are pretty big numbers, in the high thousands.

Bill: Oh! [Said with fake shock.] Relative to you, that’s a lot. Relative to the economy as a whole, do you know how much they are?

Emily: No. But five digit layoffs seem pretty big.

Bill: How many people are in the labor force in the US—how many people are in the population?

Emily: Isn’t it…300,000,000?

Bill: 330,000,000. The labor force is about a little more than half of that. So a couple thousand out of 160,000,000 is…

Emily: I don’t know math. I can’t do proportions in my head.

Bill: A very small amount. Each week, 200,000-300,000 people file for unemployment. You don’t always hear about it in the news like when Disney does their layoffs but that doesn’t mean it’s not happening. That’s the churn of the economy.

Unfortunate as it is for me to admit, he is right on all fronts: according to an article in the Wall Street Journal from earlier this month,

The U.S. added 1.1 million jobs over the past three months and ramped up hiring in January. That appears puzzling, given last year’s economic cool down, signs that consumers are pulling back on spending as their savings dwindle, and a stream of corporate layoff announcements, particularly in technology.

Driving the jobs boom are large but often overlooked sectors of the economy. Restaurants, hospitals, nursing homes and child-care centers are finally staffing up as they enter the last stage of the pandemic recovery. Those new jobs are more than offsetting cuts announced by huge employers such as Amazon.com Inc. and Microsoft Corp.

Employers in healthcare, education, leisure and hospitality and other services such as dry cleaning and automotive repair account for about 36% of all private-sector payrolls. Together, those service industries added 1.19 million jobs over the past six months, accounting for 63% of all private-sector job gains during that time, up from 47% in the preceding year and a half.

By comparison, the tech-heavy information sector, which shed jobs for two straight months, makes up 2% of all private-sector jobs.

Still, I can’t help returning to my personal experience, especially when this conversation has taken up so much space in my life lately. The past three months have been a constant wave of job applications being sent out and rejections being brought back in. Worse still, I have friends who are in the same situation as me. While yes, selfishly, it is nice to not be alone going on this bizarre journey, the catch is that I feel my frustration multiply each time any of us doesn’t get a job.

What I wanted to know was why, with this combination of low unemployment numbers and not-so-mass layoffs, my friends and I personally still find ourselves floundering in the job market, blatantly disregarding my dad’s constant argument.

I asked:

Emily: Why is it that there are, at the same time, these low unemployment numbers, mass layoff announcements, and an increasing difficulty of getting re-hired? This is not just a personal anecdote but from talking with other people who were laid off around the same time.

Bill: In the same type of industries?

Emily: Different. Compare me with one of my friends in the tech industry.

Bill: Would you consider those white-collar jobs or blue-collar jobs?

Emily: Mainly white-collar.

Bill: Do you know the percentage of white-collar jobs relative to blue-collar jobs in the economy?

Emily: I don’t know.

Bill: In the past 50 years, the number of white-collar jobs have exploded and now make up approximately 85% of total employment and blue-collar jobs make up about 15%. Obviously, there’s a lot more people working today than in the 1970s and 80s but the number of white-collar jobs have grown a lot faster than blue-collar jobs.

When people lose or leave a white-collar job, they are less likely to accept or even be offered a blue-collar job because of the lower pay and different skill sets, whereas a blue-collar worker is much more likely to accept another blue-collar job. Currently, since the pandemic-related shutdown, there’s a greater number of blue-collar jobs available than white-collar jobs available.

Emily: I think the reason my friends and I are almost hesitant to apply for blue-collar, service industry jobs is because we’re told you are not paid a living wage there.

Bill: Going down the socialist route again?

Emily: You look at the hourly wage for some of these positions and you do the math out and it isn’t in line with what you were making at a previous position of yours, like you had said.

Bill: And that’s to support the lifestyle you’ve become accustomed to?

Emily: To pay my rent. I’m looking at different jobs to pay my rent.

Bill: I hear you. I hear you. When I lived in New York City, I could not understand how somebody who did not earn a high income could live there. Yet, more than half the population does. I think it comes back to your circle, what you’re accustomed to, the standard of living that you want to attain. The majority of people get by on $12, $13, $14 dollars an hour. You would if you had to, but right now you’re not at that point so you’re not forced to do that.

If you were, yes, you could get by on that. That could be a suitable living wage for you. In general, people don’t understand that they all have these expectations, and if they can’t achieve them, then it’s not fair. Reset your expectations.

In researching this piece, I used MIT’s Living Wage Calculator for someone like me who lives alone in New York City. As a single adult with no children, the minimum wage is $14.20 but my ideal living wage is $25.65. What this means is that while the minimum wage in New York comes out to approximately a $29,500/year salary before taxes, most people in my situation would need to essentially double that in order to afford standard living fees in NYC.

While my dad is correct in stating that people can and do live on a wage of $14.20, it doesn’t mean that anyone should. You could say I’ve taken this down the socialist route but I think that’s sometimes a cop-out response to this conversation.

We don’t need socialism to pay people enough to survive—we need people to survive, period, which is why wages should be proportional to the cost of living in an area. If we are going to live in a society that demands our participation in the economy—probably the most pro-capitalism statement I’ve ever made in this newsletter—we shouldn’t have to struggle to continue to play the game.

As my dad and I were talking, I realized that a major factor in my spending habits is, as shameful as this is to admit, influencer culture. I know I’m not alone in this, given how many times I’ve either heard or said the sentence, “I bought this because Alix Earle used it in one of her videos.”

Influencer culture has led to some positive spending trends, like Gen Z’s embrace of dupe culture, as well as horrific ones, like the glamorization and overabundance of fast fashion. But, whether good or bad, real or staged, being online can make you feel like everyone you know is spending money all of the time.

I asked my dad:

Emily: Can you track cultural shifts in the economy? For my generation, a big shift for us has been influencer culture. You want to display what you buy as you buy it, go online and say, “Just bought this, I really like it. You should buy it, too.” For at least people in my circle but also just people of my generation across various income levels, that seems to be an overall trend—we make money to almost immediately spend money to live or at least portray that we’re living a certain lifestyle.

Bill: That’s gone on since the beginning of time. Before social media came about, it was your car and how you dressed because that’s what people saw and stuff like that. And before that, it was the horse and carriage you had and the clothes you wore. It’s always been that case, now it’s just more in your face, more so for your generation than prior generations.

It comes down to this: do you work to live or do you live to work? That’s a judgment you have to make in your life. If you want to work so that you can have a certain lifestyle or if you want to live so that you could work and maximize your income, that’s a whole different ballgame.

The key is finding your happy point. Making money doesn’t always make you happier, or having money doesn’t make you happy. It’s what you do with it that should make you happy and how you treat other people, which has nothing to do with money.

By the way, can I say, that ‘live to work, work to live’ thing came from a friend’s dad, named [leans into the microphone] Jack Holt Sr.? He relayed that to me back when I was about your age and struggling to find a job and career and he met with me and he said those words to me and that never left my mind.

Emily: Where do you fall in that—do you live to work or work to live?

Bill: I haven’t figured that out yet. I think when I was your age, I was more live to work and I’ve taken a step back and started to enjoy life a little more and work less, or not put as much stress on the work part.

Emily: I’ll make sure to put that in and give a shout-out to [leans into the microphone] Jack Holt Sr.

Bill: Jack Holt Sr.

The happiest I’ve been these past three months has been in the moments that have nothing to do with my employment status, and, in fact, I’m able to forget about it entirely. As we discussed with Sandra Etuk last year, there really is no way to opt out of capitalism so I know I’ll have a job again. But maybe one day I’ll be caught up in the churn once more and become one of the 200,000 filing for unemployment during a particular week—genuinely, who knows.

As I’m reckoning with my place in all of this and how I approach employment, I hope that I’ll one day reflect on this period as the time I detached myself from my job. Yes, I am still working to live as I think a lot of people reading this are but recently, the living part has come to mean so much more to me without the work there, too. I’m happiest when I get handwritten cards and skip up the street singing Grease songs poorly and have four people cooking a single pasta dish in my kitchen.

I will still always be an easy target for the TikTok gworls to sell their sponsored goods to, and I’m even more empowered than ever to fight for the right to a living wage, but I don’t know if I’ll ever find my happy point in a job again. (That said, please hire me!!!!)

The Future? In This Economy?

My dad will undoubtedly be back eventually to explain another facet of the economy to me and all of you because not only is this all incredibly important to understand, it is—and this may be printed, framed, and hung on his wall—a little fun to talk about.

But for everyone’s sake, let’s hope that’s not anytime soon as we want to preserve the current trends:

Emily: In your mind, again barring another pandemic or exogenous shock [pronounces it wrong]—

Bill: Exogenous [pronounces it right].

Emily: Exogenous [pronounces it right]. I already forgot how it was pronounced.

Bill: I didn’t pronounce it right until just now. English is not my first language—math is.

Emily: [Quite honestly the biggest eye roll of my life.] Alright…what do you see the economy looking like in the next year and five years?

Bill: This next year, being 2023, is to have growth in the 2-2.5% range. I think we’re going to be stronger in the first half than the second half of the year. And then start to slow down a bit as the impact from the [gibberish] policy hampers the growth in the second half of the year—

Emily: Can you enunciate that a little bit better so I can transcribe this?

Bill: The impacts…from the tighter monetary policy—

Emily: There we go—

Bill: —Hampers growth in the second half of this year. The tighter policy that started this time last year and is continuing right now but at a much slower pace will hamper growth in the second half of this year. At that time, the tighter policy will change to a looser policy as the Feds start to lower interests rates either late this year or early next year, and that will give a boost to growth for the next two to three years after that which gets us to the five-year window you were talking about.

Emily: How much do you want to charge E4P readers for this information that you’ve just provided?

Bill: Well I think that E4P subscribers should pay at least $50 a story, or $50 a click—

Emily: For this piece alone?

Bill: No for all of your pieces! For this piece alone, I think we’ve gotta charge at least $500. You should get paid $50 every time someone clicks on your story.

It would be a little funny if I put the rest of the article behind a paywall at this point…I’m not going to but it would be funny if I did.

Not only are we giving you these economic projections for free, but we’re also offering some positive energy from—and anyone who has met him in person will laugh at this—Bill Sharp to end on:

Emily: I know you shared the advice that [leans into the microphone] Jack Holt Sr. gave you when you were my age, but what is your best advice for someone like me who is in this job market, hearing all these things, and is not—

Bill: Happy?

Emily: Yeah. Who is struggling in this job market right now?

Bill: Persevere. Things will change. Stay positive, keep working hard, get up each day, do something constructive, and things are going to get better.

Emily: Is there anything else that I haven’t asked about that you think is important to share?

Bill: I think most of you young people should be focused on how you’re going to take care of your parents when you get older. That should be one of your top goals in your life.

Thank you to my dad for returning to help me make sense of the economy again and for not telling me that I should have taken an economics course in college once during this conversation—a stunning achievement for him.

To thank him, I’ll let him have the last word:

Emily: Why economics? Like why are you into economics?

Bill: I’m sorry, are you asking me why I’m breathing?

Emily: [I lied. This was the biggest eye roll of my life]

Bill: What have we discussed through the years? Economics is everything.

Emily: I know but I’m trying to make you more endearing to readers.

Bill: Oh, that’s not going to happen.

I think this could be referred to as “cheugy rizz.”

Trust and believe I got an earful for saying “massive layoffs” one time.

i <3 bill

I adore Bill (an Econ dad I would love to meet, thank u v much)