Cite My Sources? You Mean My Beautiful Mind?

This is like if that Covid "Imagine" video didn't suck

Last week, the president signed an executive order to cut federal funding for PBS and NPR. I’ve been trying to find the right words to articulate how I feel about this for several reasons, not in the least because today’s piece is on why our imaginations may be our most important survival tool. Ultimately, I decided that I don’t want to dwell on it too much, but I did want to say this: while it is not the most violent thing the Trump Administration has done by a long shot, it doesn’t make it less insidious.

As for today’s piece, I’ve been wanting to interview this guest for a long time. I met Bhavya very serendipitously at a coffee shop in London. We followed each other on Instagram, and I did what I do best: silently watching her build a really cool life from afar. But over the past couple of months, as I’ve struggled with speaking out against this administration in a way that does more good than crash-out-inducing harm, I’ve found myself both gravitating to and responding to Bhavya’s online commentary.

There is something comforting about witnessing someone grapple with the same thoughts you’re having and find a solution (or at least the start of one) in a place where you’re still seeing an increasingly maddening question mark. It’s nice to know you’re not crazy for the emotions and the fear and the desire to buy out a wreck-it room franchise, but that there’s another way of approaching it all that might help you keep your nervous system from crapping out.

That is, in essence, what today’s piece is about: when I asked Bhavya what she wanted space to talk about, she mentioned how the lack of imagination is holding our society back from wanting, asking, and fighting for more. I completely agreed, and voilà!

This week, we are talking about the key critical importance of expansive thinking on both a global and personal scale, why certain forces want you to believe there is nothing you can do to change the world, and how you can start thinking outside the lines.

Bhavya was raised on a healthy diet of girlboss culture, Bollywood, and The Devil Wears Prada, so now she thinks she can do anything AND has an unrealistically romantic perspective on the world—you’re welcome, world. Creatively insatiable, she’s always dreaming up the next project, event, or outfit—or the outfit for the event.

Rooted in liberation for all and questioning literally everything, her certified-thought daughter takes are available for all to read on her Substack, Off the Cuff (with Bhavya). But if you hate reading, she also plays dress up on Instagram, where she sometimes cosplays as a stylist at Sabka Studios (another one of her ventures—unbelievable! Someone stop her!)

Two Bitches With Hyperactive Imaginations Looking at Each Other and Going, “Exactlyyyyy”

Through researching this piece, I found that there have been a lot of scientific studies done on imagination that are behind paywalls. From what I can gather, though, there is a proven correlation between active imagination and improved mental health. A 2009 study looked at

the causal effect of deliberate mental time travel (MTT) on happiness and anxiety. More specifically, we address whether purposely engaging in positive, negative, or neutral future MTT would lead to different levels of happiness and anxiety. Results show a significant increase of happiness for subjects in the positive condition after 2 weeks but no changes in the negative or neutral condition. Additionally, while positive or negative MTT had no effect on anxiety, engaging in neutral MTT seems to significantly reduce stress over 15 days. These findings suggest that positive future MTT is not just a consequence of happiness and might be related to well-being in a causal fashion and provide a new approach in happiness boosting and stress-reducing activities.

Similarly, a 2021 study of 153 adults in New Zealand found that

higher well-being and lower depressive symptoms were strongly linked (a) to having goals that were more attainable, under control, and expected to bring more joy and (b) to goal-directed imagination that was clearer, more detailed, more positive, and less negative.

So what happens when we take the practice of imagination and use it to envision new realities for ourselves and the world around us? One in which, say, America has a plurality voting structure so more voices can be represented in Congress? Maybe one in which our healthcare system isn’t tied to our employment, and works to keep us healthy rather than hoping we get sick? Or even a reality in which I say I want to bleach my hair just to see what it would look like without everyone around me yelling that that is a bad idea?1

To kick off today’s piece, I wanted to ask Bhavya exactly that (kind of):

Emily: We've talked about how people seem unable to imagine a different reality than this one. Can you explain what you mean by this? What do you wish people would think about differently?

Bhavya: I think as a neurodivergent person—and just a person with a penchant for dreaming up all sorts of different plans and characters for myself to embody—growing up, I assumed that everybody used play and imagination to create a life for themself. I assumed that we were all just writing the stories of our own lives, playfully creating narratives for ourselves out of thin air.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to look around and realize a lot of us are just following what we’ve been told, or a path that was laid out for us by someone or something else—be it our parents, society, or online coaches and gurus telling us they have the key to help us unlock our dream life.

I think as human beings, we are actually hardwired to crave safety and familiarity, even to the detriment of our own life experience. We cling to what we know, or what others say they know, rather than setting off on our own individual journeys to discern who we are, what we actually want, and how we want to get there.

I also think we live in a world, especially in the U.S., where our society and the powers that be (aka capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, and all their upholders) are actually incentivized to create a population that’s scared to imagine something different.

We need look no further than the structure of our education system—where children are woken up at 6:00 am to go memorize historical facts and figures that are completely divorced of context and actual meaning—or the dynamics of the modern nuclear family— where the average American parents are just trying to survive and maybe save some money for retirement; they don’t have time to pause, step outside their reality, and imagine something different, for themselves or for their children.

Ultimately, peoples’ inability to imagine, or even to play (and I don’t just mean playing racquet sports once a week), deeply benefits the people who currently hold power within the overarching social hierarchy, and within the institutions that uphold it. And so they fund the creation of media and music and cultural trends that uphold a lack of imagination.

Consider zombie or apocalypse movies in Hollywood. How come, when society breaks down, we never see neighbors banding together and locking down in an abandoned mall? How come we never see the immigrant families feeding everyone, while other people run from store to store gathering supplies to distribute? How come we never see mutual aid in practice on our screen?

It’s better for the current power structure to make us all believe that when things fall apart, we can’t survive without them.

We can’t govern ourselves communally and compassionately, right?

The thing is, we’ve seen time and time again that when shit hits the fan, human beings step up for their own survival, and for each other.

When Hurricane Katrina hit and the levees broke in Louisiana, the federal government completely abandoned those people, except to arrest or outright murder anyone trying to procure food from abandoned grocery stores. It was Louisiana community members who ultimately stepped in to coordinate relief efforts, provide and distribute aid, and quite literally rebuild their communities brick-by-brick.

More recently, we can look at the devastation across North Carolina in the wake of Hurricane Helene. Many of the towns that were washed away in the floods still have not regained power or water. And average Carolinians are having to carry the entire burden of rebuilding their communities and their lives, with next to no support from the government.

Just before Bhavya and I started working on this piece (serendipity strikes again), I saw the below video of actor Penn Badgley explaining that he is trying to change his life radically, but that his growth as an individual is “inextricably linked” to the growth of the world around him. As he puts it, “you can’t have a changed society without changed individuals, and you can’t change as individuals that much without that much of a changed society.”

Thinking about her previous response, I wanted to know Bhavya’s thoughts on this:

Emily: Is it important to want more and imagine bigger on a national and even global scale, as well as on an intimately personal one?

Bhavya: UGH I love Penn Badgley and what he’s saying here really hits at the core of both why imagination is vital to any type of true, wholesale change—whether personal, spiritual, or societal (and they are all inextricably linked, as he says)—and also why imagination is such a threat to the current world order.

I actually think that once we start seeing our own personal growth and healing—which is on so many of our minds these days, especially as wellness has become an entire industry of its own—as innately tied to the growth and healing of our society, we actually start to understand why it’s so important for us to advocate for systemic change.

Emily: Why do you think people are scared of wanting more, or are unable to see that things can just be different?

Bhavya: Honestly, I think it’s just hard. Especially when so many of us are in survival mode—due to trauma or just the realities of living under capitalism—we don’t want to have to come home from a 12-hour shift at work to then critically examine our role within a system that was broken before we were even born.

We all feel the desire to cling on to a version of reality where we’re doing “our best,” where whatever we can comfortably do—without actually changing our lifestyles or addressing our own hypocrisy—is enough; where the pursuit of finding your individual joy (or just avoiding falling into a deep depression) is the extent of your resistance, but everyone says you’re already going above and beyond, and to prioritize your peace.

Counterintuitively, I’ve found that as we start to relinquish that fear of holding ourselves to a higher standard and maybe falling short, and when we stop dissociating from our real lives—staying just present enough to keep our heads down at work, be fun and flirty on the weekends, and maybe complete all our chores—we actually start to feel more connected to ourselves, the world, and the people around us.

Tuning back into reality is the first step, and unlearning the fear of imagination is the second. And though embarking on that journey is scary, quite quickly you realize there is a much deeper well of joy to draw from, and it’s rooted in community care and community healing.

In that no man’s land between Donald Trump’s re-election in November and inauguration in January, I started comforting myself by clinging to a resolute thought.

With each new Cabinet pick, the reality we are now living in was becoming increasingly clearer: these headasses were being selected for their utter disdain for American democracy, a system they saw as unkind to their political ideology. (A little ironic, no? Ross Vought and the creators of Project 2025 dreamt up a government that didn’t exist but would benefit them.)

In a tone that was decidedly not Mel Robbins-approved, I just kept thinking: let them.

Let them burn down the government. Let them turn our existing system into a non-functioning nightmare for the sake of besting wokeness. Let them ruin America as we know it, and let others find ways to build a new democracy in its wake.

It’s clear that our judicial, legislative, and executive branches are functioning primarily for their own gain versus for the betterment of the American people. All of us, across all ideologies,2 feel varying degrees of unseen by what is supposed to be a representative democracy. More to it, the majority of institutions that make up our federal government have foundations rooted in and built on hatred and violence.

Earlier this year, I wrote that “the hatred and the anger and the fear that has driven [Trump] can only burn for so long before they give out.” What if, in the wake of his destruction, we make good on the promise of building a government truly by and for the people?

As much as thinking about this brought me (and continues to bring me) some peace, it also drove me crazy—what would the logistics of installing this government look like? How could we trust each other again after such a polarized time? Did anyone besides me even remotely believe this could come to fruition?

It’s a small comfort, but the answer to the last question is yes. In a July 2020 interview with Megan Rapinoe for her show Seeing America, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez stated that:

…perhaps we are in the downfall of the broken way. This was not built to last. Inequity, injustice, is not built to last. It lasts a long time, it could last hundreds of years, but ultimately, it crumbles into this, you know? A small cohort of incompetent people that create damage. And from that, something new can spring.

And so maybe something is declining right now, but maybe it deserves to decline.

I saw this clip for the first time in December and felt incredibly validated in my argument, not simply because we were saying similar things, but because AOC said this four years ago, while still under the last Trump presidency. By her logic, that must mean the broken system was in further decline, and we are now closer to something new.

I want to believe that thinking like this, that having daydreams of a world where I don’t fear the impact each new Truth Social post will have on my wellbeing, is not fruitless. But I often feel this weird societal influence telling me to be practical, be reasonable. Curious to know if Bhavya ever felt the same, I asked:

Emily: To me, it seems there's this idea that daydreaming is frivolous, and I've always just assumed that was because it's often coded as a feminine habit. Do you think that's the case, or is there more to it?

Bhavya: This feels somewhat like a question of the chicken and the egg. Did daydreaming get a bad rap because it’s usually done by girls and more feminine people? Or did our patriarchal society slap the label of frivolous and feminine on daydreaming to dissuade people at large from doing it?3

I’m not sure what the answer is, but I do know that to me, the narrative around daydreaming has always been that it’s a “childish” habit, and that daydreaming has no tangible effect or output, especially in a capitalistic society that measures value in terms of physical goods or services produced. But what if the product of daydreaming is just as potent, if not more, than goods and services? What if imagination is an asset in its own right? Especially when a huge proportion of the population is unable to tap into that generative, expansive way of thinking.

How come daydreaming is pooh-poohed as a waste of time, but consultants make the big bucks for re-imagining how companies can do business? Probably because the latter are using their imaginative powers to create value for the shareholders.

The vibe of the day is really giving: “How do you balance your outsized obsession with the Met Gala with your socialist beliefs?” So let’s lean into it and interrogate some of the other systems keeping us from dreaming of more.

Imagining a Radically New World

I don’t want to be the white girl who waxes on about the lasting impacts of colonialism, but I would be remiss not to highlight the fact that the white supremacist aspects of colonizer ideology also harm white people. To cling to the idea that you are undeniably better than anyone else stops you from ever learning, growing, or changing—in other words, you become a has-been.

I know talking about colonization often kills the vibe, but walk with us a bit. I asked Bhavya:

Emily: In what ways do you see the effects of colonialism on our collective lack of imagination?

Bhavya: I think colonialism has everything to do with our collective lack of imagination. And everything to do with the structures that comprise the world we currently live in. Everything we see around us, especially as occupants of the Western world and/or formerly or currently colonized regions,4 has been constructed for us by the “colonial imagination.”

I think that’s really important to recognize. We often fall into this trap of thinking this is just how things are, or this is how the world has always been. More often than not, though, that’s just not true. In fact, so much of how we live and work and interact today was dreamt up by people who lived only three or four generations ago.

The power in recognizing that also comes from understanding that if a bunch of white people could dream up a reality that centered them and their supremacy, and if a bunch of men could conceptualize a reality wherein they were the leaders, the rulers, and the heroes of every story, then we also have the power to imagine a reality—a different reality.

One made in the image of true inclusivity and community care. One that prioritizes children and mothers, that encourages the democratization of education, and provides equal resources and access to all people.

That reality is possible as long as we can imagine it. A decolonized reality is possible as long as there are people decolonizing their capacity to imagine. But, if we don’t take the reins and imagine a reality for ourselves, we are actively resigning ourselves to living complacently within a reality defined by and made for someone else.

Emily: As a society, we talk about unlearning taught behaviors and mentalities. But I think what you're encouraging here is for all of us to learn a way of thinking and being that many of us may never have been taught. What do you make of that assessment?

Bhavya: 100% what we’re talking about here is something that most of us were never taught. In fact, many of us had our capacity for imagination broken down over time, by parents telling us to be realistic, by society telling us that the best we can hope for is to just survive.

So not only do we have to learn a way of thinking that hasn’t been taught, we have to separate ourselves from the narratives we’ve been fed about what is and isn’t an acceptable use of time and energy. This actually brings me to your question about daydreaming, which I’ve been thinking about since I received your questions!

I wouldn’t be me and this wouldn’t be Emily For President if I didn’t try to use historical research as a tool for understanding the future. I wanted to know if there was anywhere we could all look to see this way of thinking Bhavya is advocating modeled for us, so I asked:

Emily: Are there any historical references people can look to for inspiration (or, perhaps, proof) that life can be bigger and better than what it is right now?

Bhavya: Absolutely—we can reference historical figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela, who dared to dream of a world without apartheid, which at that time was a radical notion. But apartheid did end. The global standard for the treatment of humans shifted.

While we can equivocate on the fact that apartheid, segregation, and slavery all still exist, albeit in more covert and nuanced ways, the fact of the matter remains: we no longer exist in that same reality. Someone dared to imagine differently, and though it took time and a lot of pressure, standards shifted, human rights were defined more clearly, and precedents were set. Precedents that lay the foundation of how we continue to move in the direction of a better, kinder, more equitable world.

But, I would also posit that even more than looking at historical figureheads, it is in looking at everyday people and the campaigns and changes that happen at the grassroots level in day-to-day life where we can find both proof of and inspiration for a different way of life.

I recently watched a TikTok made by this random dad. He was telling a story about how he took his kids to the park to play and noticed that all the swings, including the inclusive bucket swing, were taken down. A little while later, another family arrived at the park, and upon seeing the lack of swings, their child burst into tears. The parent explained that they had gone to every park in town and not one had accessible equipment that the child could use. The bucket swings at this park were their last bet, and now they were gone. The dad making the video said the family ultimately left without being able to play at the park.

Later, he picked up the phone and called the local parks and recreation department—he explained the entire situation and what he had witnessed and implored the parks and rec staff to reinstall the bucket swings. A few days later, he received a call from Parks and Rec: they were providing an update that they had just ordered four new bucket swings and would be installing them that week.

It’s in small moments like this where you can see the power of imagination and action working together. That dad dared to imagine that Parks and Rec might listen to him if he called. He dared to imagine a world in which they would be empathetic to a disabled child’s desire to play on the swings, and that using his voice, especially as a White male, could make a difference.

He could have just resigned himself and grumbled about how “The Parks Department is ruining the parks.” But instead, he looked for a better outcome, and ultimately it came to be.

Maybe the solution here is not necessarily just dreaming of better, but actively practicing empathy to build the kind of world you want to see. If you are someone referenced in Ellie Light’s piece who thinks very locally, improving your immediate sphere (like the dad calling his parks and rec) could be a good place to start. But real change will only come when we all extend the kindness we reflectively show ourselves and our neighbors to people we have never and likely will never meet.

For anyone not currently in or in support of the Trump Administration, that shouldn’t be too much of a stretch…but maybe that’s just the woke mind virus eating away at my brain.

Free Your Mind, Release Your Inhibitions, Feel the Rain on Your Skin, and the Rest Will Follow

It might seem odd to ask Bhavya the following question this late in the piece, but I wanted to paint the big picture before analyzing Bhavya’s personal snapshot. Since we’ve acknowledged that expansive thinking isn’t anyone’s default setting in this day and age, I wanted to know:

Emily: Do you feel you're fairly good at imagining outside the box yourself, or is this something you're still practicing?

Bhavya: Not to toot my own horn, but I do think I’m quite good at imagining outside the box, for myself and for the world around me. One of my favorite things to do is dream up new characters for myself to embody and new lives for myself to live, especially through getting dressed and styling myself. I love thinking about initiatives to start and asking the question, “If what I’m looking for doesn’t exist, how can I create it?”

I grew up a very, very imaginative child. Sometimes it was entertaining to others, but often the questions I would ask were triggering and alienating, especially to adults. By the time I reached high school, a lot of that imagination had drained out of me; what was left was a version of myself, a mask if you will, that was just playful and exciting enough to be enjoyed by others, but not asking such radical questions that anyone was forced to question their way of thinking. God forbid!

When I graduated college, I was so focused on achieving success within the traditional frameworks—get a degree, find a boyfriend, get a high-paying job, move to the big city, get engaged, get married—and honestly, I checked them all off. I was living the life. But I felt like I was hardly living at all. I had killed my imaginative spirit and resigned myself to a life of “normalcy,” where creativity was reserved for hobbies and the main focus of life was sustaining oneself.

It actually took me healing my inner child and realizing that so much of what I had been taught by adults in my life—that life is hard and that we all have to focus on making money and surviving and the best way forward is the most straightforward, well-worn path, with the least risk—were actually just their version of reality.

They had projected their imagination onto me, and as a child, I accepted it as fact. But once I realized that each of us actually has the power to create our own reality through the process of imagining, I stepped into this new, freer, far more playful version of myself. One that gave myself permission to be the ultimate arbiter of what is possible and what is not (spoiler: there’s very little that falls into the “what is not” category for me).

And quite honestly, from then till now, my world has opened up. It has blossomed into this intricate tapestry of creative projects and a vibrant community of like-minded and liberation-oriented people, all of which, quite literally, sprang forth from my mind. I imagined it, and it all came to be.

I want to pause here simply to create a little space in this piece to celebrate everything Bhavya just said.

Not only did her response remind me of some of Avery’s thoughts on achieving traditional life goals, but I literally just had a version of this conversation with my therapist recently, in which I realized I’ve surrounded myself with so many people who are already living in alignment with themselves, or are striving to be. Friends who are pursuing career paths that don’t break their spirits, hobbies that bring lightness to their days, and clothing items to dress as the person they’ve always wanted to be. They’re not tied to arbitrary metrics or frameworks so much as they are focused on building lives that reflect who they are.

The thought that made me smile while talking about all of this is just how undeniably cool it was that all of these people have found ways to truly be themselves.

I think that’s the ethos of what I wanted to talk to Bhavya about today. At the core of imagination is a desire to be authentically happy: you’re either imagining something bigger and better for yourself, or the sheer act of imagining is what is bringing you joy, like kids building dream worlds on the playground.

In the last section, I asked Bhavya for historical examples of thinking bigger as a means of finding places where we can look for inspiration. But as I’m writing all of this and reflecting on her response about that one man who made a difference, I realized we already had inspiration at home.

I wanted to reframe my previous question and ask:

Emily: What is one thing you imagine or imagined for yourself that felt scary to admit or act on? What is one thing you're imagining for our collective futures?

Bhavya: I think even once you’ve imagined something, admitting it and sharing it with people is terrifying. It might even be the hardest part of the entire process. It’s one thing when it’s just daydreaming, but another thing entirely when I’m admitting to the world that I want something I don’t yet have, that I want to be something I’m not yet.

It’s an incredibly vulnerable thing, but once you finally push past that fear—and realize that what lies on the other side of that fear is so much greater than what you could even imagine—you become, quite literally, unstoppable.

In 2023, right after the genocide in Palestine began, I was deeply disturbed by the lack of care I saw in the people around me. Even my loved ones seemed more content to look away and focus on their own lives, often encouraging me to pay less attention and reminding me that “there’s nothing we can do.” I think it was in hearing there’s nothing we can do over and over that I started to think, “What CAN I actually do?” And so I started Two New Friends, a community building initiative based in D.C.

Selfishly, I started Two New Friends because I was sorely craving a community of like-minded people who did care, and who sought liberation for all people. And not just physical liberation, but emotional, spiritual, mental liberation—all of which amounts to a greater collective capacity for imagination. I wanted to meet people who, like me, felt that the world could change with the right vision, and that we ought to work toward that goal, even if we never saw it actualized within our lifetimes.

At the same time, I wanted to bring other people into that way of thinking—not by hitting them over the head with academic rhetoric and arguments for “expanding their mind,” but rather by modeling a way of living and being that was different than the norm.

By inviting people in, offering free coffee and pastries, and creating a deeply intentional and welcoming space, that’s exactly what we’ve been able to do. Now almost a year and a half in, the Two New Friends community has grown into a vibrant and interlinked ecosystem that continues to radiate outward into new events, new friendships, and a slow, but sure, shift in peoples’ belief that they actually can actualize the daydream in their head.

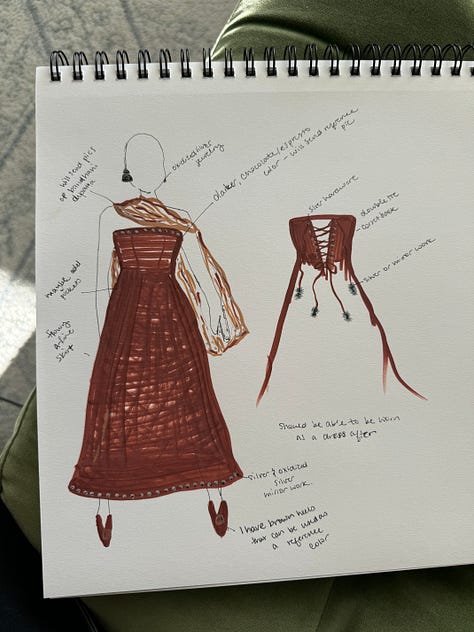

More recently, I’ve been exercising my imagination in new ways–this time for myself and my dream career. Since college, I’ve been in corporate jobs doing the most practical version of writing I could find, but it always felt like a cheap tradeoff for the richer, multi-passionate creative life I’ve always (somewhat secretly) desired. I’ve been slowly conceptualizing and clarifying my vision of what that multi-disciplinary creative lifestyle actually looks like for me, in practice.

Excitingly, I’m in the beginning stages of finally executing on all my ideas, and to start, I’ve launched my two pet projects: Sabka Studios, a vintage curation, styling, and creative studio, geared toward helping creatives step into the fullest, most authentic version of themselves, both on-stage and off, through styling and creative direction (and maybe a little vintage personal shopping), and Off the Cuff (with Bhavya), an editorial space where I’m writing long-form essays, spotlights on creatives who are doing things imaginatively and bringing their identity and politics into their work, romantic reflections on life, and so much more.

The core ethos of all these projects is to encourage people to think just a little more authentically and intuitively, and to get a little more comfortable imagining and dreaming along the way. I think it’s imperative that we recognize we are the masters of our own destiny, the arbiters of what is real, and the stewards of our own imagination.

If we can imagine it, anything can come to be.

“What If I Flop?” But Darling…What If You Slayed?

Something I’ve been noodling on within this conversation is the role fear plays in limiting the scope of our imaginations. We’ve talked around this notion of being too afraid to think bigger because we’ve never done it before; I asked Bhavya about any apprehension she had sharing her imagined future with others; our current administration stokes fear of the unknown or unfamiliar, and removes access to the information that would show us different isn’t synonymous with scary.

Throughout our previous conversations about change here at E4P, I repeatedly brought up the very simple response to the question, “‘Why are people scared of change?’ and found that

neuroscience research teaches us that uncertainty registers in our brain much like an error does. It needs to be corrected before we can feel comfortable again, so we'd rather not have that hanging out there if we can avoid it.

We also fear change because we fear that we might lose what's associated with that change. Our aversion to loss can even cause logic to fly out the window (X)” (X).5

Unlike Bhavya and her imagination, I can’t yet toot my own horn and say I’ve fully gotten over my own fear of the new and unknown despite talking about change near-constantly on this newsletter. I’m better than I was only a few years ago, and certainly am less scared of cutting out on my own when it means staying true to who I am and what I want.

But even still, it can be hard to think big thoughts and then put decisive action behind them. I wanted to know if there was anything specific Bhavya did to help her grow more comfortable with this way of thinking and being:

Emily: What would you encourage people to do to try to think bigger? Are there exercises or practices that have helped you?

Bhavya: I think for me, the first thing that re-invigorated my creative, imaginative spirit, was finding my personal style. In 2022, I embarked on a personal style journey, partially because I realized my body had changed a ton in the preceding years and I no longer knew how to dress for my body, and because I craved a level of self-expression in my clothing and appearance that I had only idolized in celebrities and seen in magazines growing up, but which I had never embodied myself.

At first, getting dressed was so incredibly difficult. Nothing felt right, I didn’t even know what I was trying to capture, and I wasn’t sure if I could even execute the types of looks I was imagining. But as I kept at it, and as I continued to make small, personal decisions while getting dressed each day, I could feel the muscle becoming more toned and my own taste and authentic self-expression getting stronger and more reflexive.

Stepping into my authenticity was a game-changer, and watching my style evolve (I spent a lot of time scrolling through the Outfits album on my phone) solidified to me that I actually had the power to change anything as long as I had a vision of where I was going. And taking it a step further—that I could envision anything if I just let myself dream unfettered by anyone else’s limiting beliefs.

For me, personal style was the vehicle for wholesale transformation but I think it can be anything that requires you to make decisions from an intuitive, authentic place. Start incredibly small: imagination can be exercised in the tiniest of ways—choosing what colors you want to use for a sketch in your notebook, picking out your jewelry combo for the day, taking a different route on your walk home and bringing novelty into your own life, just because you can. Because you have free will.

The other concrete tip I would give people, especially in the age of smartphones and algorithmic social media, is to curate what you’re consuming. Our capacity for imagination is largely rooted in what we see, hear, and experience repeatedly. Like I said before, we as humans often need things modeled for us before we can imagine them for ourselves.

So, use your algorithm to your advantage. Follow creators who are talking about radical imagination, possibility, authenticity, self-expression, etc. One of my favorite creators by far is Kristianna on TikTok. She refers to herself as a Possibility Maven and shares so much insight into how people can get comfortable imagining different possibilities, small things people can do to radically impact their communities, and so much more. So go follow her, seriously.

In addition to curating my social media feeds, I’ve even set up my phone with Pinterest board widgets that show me a rotating carousel of inspirational messages, reminders that I can do anything I set my mind to, etc.

I think the biggest thing to keep in mind and really internalize is that ultimately your mindset is what you make it. And we have primal little monkey brains that respond to repetition and reinforcement—so why not use that to our advantage?

During my research, I found a July 2016 piece from Rebecca Solnit in which she discusses the importance of having hope in times of despair. She refers to her 2004 book, Hope in the Dark, which she wrote

against the tremendous despair at the height of the Bush administration’s powers and the outset of the war in Iraq. That moment passed long ago, but despair, defeatism, cynicism and the amnesia and assumptions from which they often arise have not dispersed, even as the most wildly, unimaginably magnificent things came to pass. There is a lot of evidence for the defense.

Coming back to the text more than a dozen tumultuous years later, I believe its premises hold up. Progressive, populist and grassroots constituencies have had many victories. Popular power has continued to be a profound force for change. And the changes we have undergone, both wonderful and terrible, are astonishing (X).

The point she spends the article proving that while 2016 (post-Brexit but pre-Trump 1.0) felt disheartening for many of us, the despair didn’t invalidate certain successes. Things had felt bleak before, and we’d still managed to achieve things like Obergefell v. Hodges, the Paris Climate Agreement, and the Affordable Care Act.6

But most importantly, she argues that

news cycles tend to suggest that change happens in small, sudden bursts or not at all. The struggle to get women the vote took nearly three-quarters of a century. For a time people liked to announce that feminism had failed, as though the project of overturning millennia of social arrangements should achieve its final victories in a few decades, or as though it had stopped. Feminism is just starting, and its manifestations matter in rural Himalayan villages, not just major cities…

We need litanies or recitations or monuments to these victories, so that they are landmarks in everyone’s mind. More broadly, shifts in, say, the status of women are easily overlooked by people who don’t remember that, a few decades ago, reproductive rights were not yet a concept, and there was no recourse for exclusion, discrimination, workplace sexual harassment, most forms of rape, and other crimes against women the legal system did not recognize or even countenance. None of the changes were inevitable, either—people fought for them and won them (X).

We don’t need to see the world exactly as it is just because that is what exists in front of us right now. It can be terrifying to think about things so much bigger and so much farther outside of ourselves I write as someone who is too chickenshit to make a concrete five-year plan, but it can be scarier to only think of a world in which a washed-up reality TV star with lifelong racist proclivities and the inability to ever get a good fake tan has the final say on what America is.

With that, I wanted to end today’s piece by asking Bhavya:

Emily: Do you think that we collectively view hope as the powerful tool that it is? Why or why not?

Bhavya: I think hope is one of the most powerful tools that we have, and, likely similarly to how daydreaming has been devalued as a feminine or childish trait, hope has too.

The powers that be don’t want you to have hope because hope means you might try to think of an alternative outcome. Hope means you still believe in your own power to effect change.

Hope is maybe what brings the potency to imagination. Because, remember, even consultants and war criminals can be imaginative. So the question becomes, what are you imagining for? For yourself and the inflation of your own bank balance? Or for the creation and proliferation of a society that cradles all of its people in a safety net of compassion, acceptance, and support?

To hope says, “I’m already starting from a place of radical belief that things can be better,” and for that reason alone, it’s imperative.

How’s that for hopecore in these trying times?

I’m in awe of Bhavya and am genuinely convinced the Universe conspired that day in 2018 to put me in her path (I wasn’t supposed to go to that coffee shop where I met her—I had gotten lost after an event and had somehow found myself there). But I’m grateful to have known her all this time and to have the chance to pick her gorgeous brain!!!

I KNOW it’s a bad idea, but I just want to see what it would look like!!!

Except MAGA, I guess?

“Whether intentionally or not, most people, especially men, shy away from anything that might cast a remotely feminine shadow on them.”

“I realize almost the entire world falls into those categories, okay? The reaches of colonialism are far and wide, but there are a few places that have stood untouched.”

I didn’t like that quotation style either.

It’s not lost on me that these are some of the most villainized initiatives under a Trump administration, but they’re all designed to help make life better for large groups of people.