Budget Reconciliation, Filibusters, and Loopholes— Oh My!

A very long-winded way for me to form a conspiracy theory that the American Government secretly makes no sense and also never has

In last week’s newsletter, I gave you all the SparkNotes version of what the budget reconciliation process is like in the Senate. This high-brow parliamentary process has often left me confused and, since this whole newsletter is simply me projecting my lack of knowledge in various subjects onto all of you, I thought this week we’d have a little history lesson on budget reconciliation and her sorority sister, the filibuster.

Both of these drama queens have been the names on everyone’s lips this past year but they often go underexplained and misunderstood, like socialism in my public school system. So today, let’s look at what these processes are, why they exist, and what effects they have on passing legislation today.

It’s Like the Saying, “God Gives His Toughest Battles to His Strongest Fighters,” Except It’s Me Giving the Hardest Explanations First to Get Them Out of the Way

Sorry to all the American Exceptionalists in the chat, but the filibuster is not unique to our Senate. It’s defined as a “procedure where one or more members of parliament or congress debate over a proposed piece of legislation to delay or entirely prevent a decision being made on the proposal” and practices of it date back to Ancient Rome.

If you are like me and have spent the past seven weeks rewatching WandaVision episodes for Easter eggs, slowly refining your super-sleuth abilities, you may have noticed that I specifically said the Senate, not Congress. That’s because the House adopted a rule adding time limits to debates on pieces of legislation in 1842 in its attempt to become America’s Favorite Chamber of Congress.

In the past, senators who wanted to filibuster a bill had to remain on the floor either singularly or in a little squad and talk continuously to delay a vote on a proposed piece of legislation. Some senators still perform a talking filibuster for extensive periods of time, such as one of my state’s senators, Chris Murphy (D-CT) who talked for 14 hours and 50 minutes in 2016 to try to secure a vote on gun control legislation.1

However, the Senate now usually pulls what I can only refer to as “the lazy-man’s filibuster”: a supermajority of the Senate support —aka three-fifths of the Senate, or 60 out of 100 senators— must vote to end debates on a proposed piece of legislation for the Senate to move to a formal vote. (Sidebar: yes, I did intentionally gender this style of the filibuster and I’ll do it again!!!)

Once the Senate moves into the formal voting period (voting to pass or fail a piece of legislation), only a simple majority —which is 50 out of 100 senators, for those of you as bad at math as I am— is required to pass legislation. Right now, the Senate is split 50/50 down party lines but Democrats theoretically have control of the house because, as noted last week, the president of the Senate is Madam Vice President Kamala Harris and she casts a tie-breaking vote whenever needed.

But if 60 senators do not vote to move to a formal vote, then the proposed legislation is concerned filibustered, and this is how the Senate has filibustered, give or take, since 1975.

Who was so messed up that they came up with something this bizarre and unnecessarily complicated?

Please forgive me for this but….. It was Aaron Burr, sir. Apparently right before he was indicted for a certain man’s murder, sir.

Technically.

Without spending too much time inspiring Lin-Manuel Miranda’s next play, the Senate originally had a precedent that ended debates by a simple majority vote, Vice President Burr asked, “Why? You barely use that rule,” the other senators were like, “He’s got a point. Let’s remove that,” they did, then everyone kind of forgot that they had the option to just talk away the option to vote on moving to a vote until the 1830s, and then the filibuster became live-action Twitter (but also not really), and NOW it’s the whole lazy-man thing.

Why in the fresh hell should I care about literally any of this?

Well, for one thing, knowledge is power and I certainly was very unaware of how this prevalent governmental process worked so I can imagine we’re all learning something and growing together. And for another, because this is my newsletter and I said so.

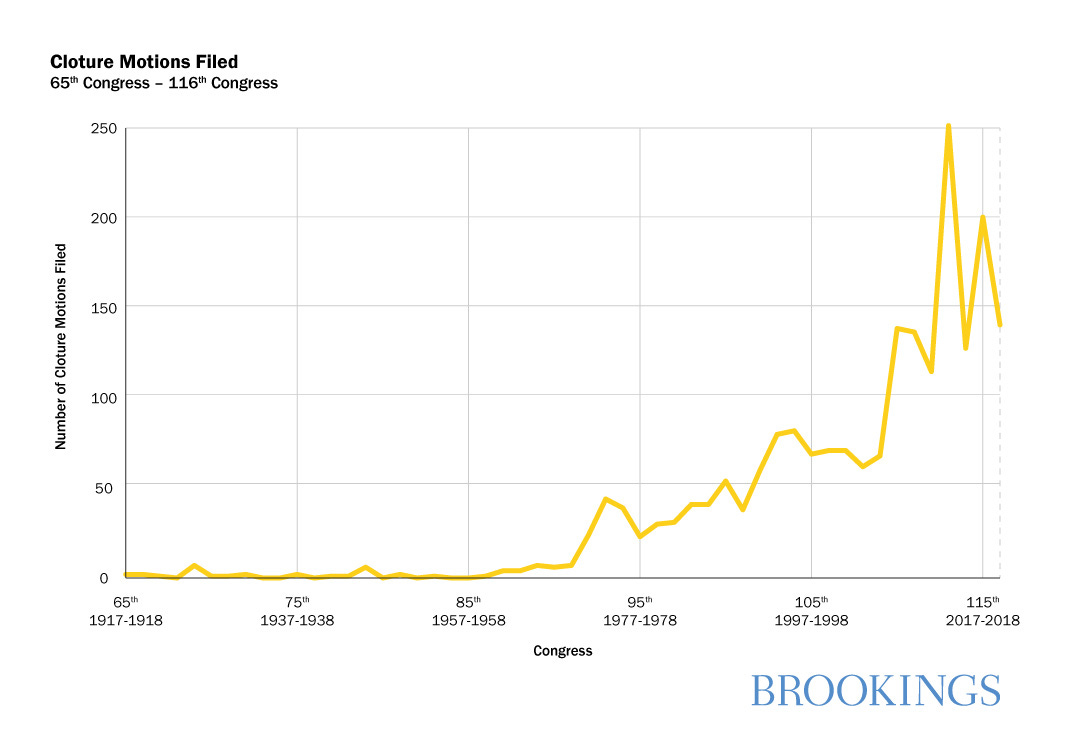

The filibuster has become an increasingly used tool in the Senate over the past few decades, as noted by the rise in cloture voting. Cloture, or (as Camille Rowe would say in just a slightly shitty French accent) closure, is the motion that kicks off the vote to move to a vote and allows space for a filibuster. As America’s most prolific historian, Wikipedia puts it,

“As the filibuster has evolved from a rare practice that required holding the floor for extended periods into a routine 60-vote supermajority requirement, Senate leaders have increasingly used cloture motions as a regular tool to manage the flow of business, often even in the absence of a threatened filibuster.”2

If you’re wondering why you specifically should understand what the filibuster is, the best reason I can offer you is this: the rise in usage of the filibuster since the 1970s has led to the Senate being unable to pass non-controversial bills that did not find a filibuster loophole (which we’ll get to in one second).

Your government should work for you and, with the prevalence of this stupid concept that is not even a granted power in the Constitution but a precedent set by the absence of a rule a known murderer suggested, it by and large has not been doing so effectively since the Bee Gees were just hitting their peak. Because the filibuster is not a constitutional right of the Senate, there are a number of reforms to change or abolish the filibuster as well as loopholes to getting around the procedure in its current state.

My goal here was to explain just the bare bones of what the filibuster is and what it does but it’s obviously very hard to simplify something this ridiculous perfectly. It’s the job of one of my favorite Instagrammers, Brian Derrick, to explain government functions like the filibuster far more concisely and eloquently than I do, so if you’re still confused as to what this all means and why it all matters, check out his video walking through the filibuster here.

Budget Reconciliation, Also Known As a “Fuck You” to the Filibuster

Forget, if you will for a second, what my dad said last week about the economy not being about money. Budget reconciliation is one of the ways the Senate is able to get around the filibuster by making everything about money.

For all intents and purposes, we are going to be focusing on the reconciliation process in the U.S. Senate. While it currently still exists in the House, it’s not as powerful. As The New Republic put it,

“Going to the floor, the House Rules Committee can waive all points of order against a bill, if backed up by a simple majority vote of the House. So restrictions in the Budget Act on the content of reconciliation bills are not that important going through the House the first time.”3

Budget reconciliation was created in 1974 as a procedure in the annual congressional budget process. What does that mean? At the start of every year, the president submits a budget to Congress who then passes resolutions in both chambers setting spending levels and targets for the next year.

Here’s where the money comes in: if a piece of proposed legislation has an impact on the budget or taxes or Congressional money, it can be voted on without being subjected to the filibuster (aka it automatically goes up for a formal, simple majority vote).

OBVIOUSLY, THERE ARE CAVEATS!!!!

This is Congress, not an overly stereotyped Netflix Original Series.

The Byrd Rule was adopted in 1985 after Senator Robert Byrd who makes a guest appearance again later in this newsletter. The Byrd Rule essentially blocks a piece of legislation from being eligible for the reconciliation process if it contains a provision considered to be “extraneous.”

As we may recall, the minimum wage raise was removed from the American Rescue Plan Act under the Byrd Rule. Essentially, it serves to narrow down the already narrow loophole around the filibuster. There are even caveats to the caveats but to make sure all our heads stay on tight, let’s play “Closing Time” and bring it home.

To circle back to the first paragraph in this section, while there are other ways to bring legislation to a vote without potential filibuster-ing, reconciliation is the easiest and broadest way to get around the supermajority cloture je ne sais quoi so it’s the best method to focus on, the most commonly used workaround, and among the simplest parliamentary procedures for me to explain.

But what’s the larger theme here, Emily? Why this? Why now?

The idea of reforming or ending the filibuster through a change in precedent (often referred to as the nuclear option because politicians are nothing if not dramatic as hell) has been floated around a lot over the last decade or so. As Brian pointed out in his video, the filibuster had only been used 60 times between 1917 and 1970 but was used 500 times from 2009-2015. This recent use (or abuse... Tomato, tomahto I guess) has decreased the productivity of the Senate dramatically and many believe it’s time for Miss Girl (the filibuster) to go.

Because everything is, doing away with the filibuster has become a political issue. Although it has been used by both parties throughout history, most notably by Southern Democrats who wanted to stop the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 19644 from going to a formal vote, more Democrats currently want to do away with the filibuster because it more frequently benefits those on the right who use the filibuster to block progressive legislation from going to a formal vote.5

Budget reconciliation can only help with so much. Understanding why the filibuster is frustrating and unproductive without a partisan skew shows us how nonsensical it is for any party to use; it has hindered the passage of legislation that can really help the American people and will likely continue to do so without any reform.

The precedent of the filibuster has already been reformed twice in the last 10 years, once in 2013 to allow for a simple majority when voting on executive branch and judicial nominees and again in 2017 to allow the same when voting on Supreme Court nominees. The filibuster can change. Like a lot of things we accepted in the 1970s, it’s time we re-evaluate the filibuster, how it became so widely accepted as fact, and what place it has (if any) in our modern lives.

Proposed legislation, like the H.R. 1 For the People Act, deserves to have a fair vote unencumbered by a pre-vote on if there’s allowed to be a vote that requires more votes than voting for a bill actually does. It’s important to demystify and better understand our government’s often bizarre parliamentary procedures because they affect us more than we often know.

On that note, happy Monday everyone!

Hate to pull an “end of a biopic in which the subject dies” vibe, but while Murphy’s filibuster did result in the Senate agreeing to hold a vote on two gun control proposals both measures failed. We don’t have time to get into the debate over gun control right now, but we’ll probably have to soon since the country is opening back up again.

Guest Starring Senator Robert Byrd!

Yes, I know about the Southern Strategy. No, I’m not going to get overly nitpicky with the dynamics of this paragraph’s partisan claims. And yes, I am still bitter that I was never taught this in high school because I do think it misconstrued some things we were taught.