Happy Sally Rooney Week to all those who celebrate, especially Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers.

As I promised two weeks ago, we’re finally going to unpack the increasingly prevalent That Girl aesthetic following closely behind yesterday’s premiere of Hulu’s Conversations With Friends adaptation. You may be wondering what in the world these two things have to do with one another: Did Sally Rooney invent That Girl? Are Zooey Deschanel and her bangs somehow involved? Does this have anything to do with Marlo Thomas? (You’re welcome, Mom.)

No to everything, but the connection between That Girl and the Sally Rooney-fication of our culture are certainly tied together by an invisible string (you’re welcome, Taylor) so it makes sense to discuss them both at once.

If you’re still confused by what this all means, rest assured: we’re in good hands. This week, Erin Raderstorf returns to explain the trajectory of the That Girl trend, discuss authenticity on the Internet, and get into the Irish brooding of it all.

Since the last time we spoke, Erin's life is completely different. She went from being a barista in LA to working at a summer camp/retreat center year-round in a small town in Virginia. She has a degree in digital studies, just bought a Subaru, and is pretty sure that Andrea from Summer House is her soulmate.

I’m Not Sorry About This

Emily: I hate to have to do this but fuck marry kill: Conversations with Friends, Normal People, Beautiful World, Where Are You?

Erin: Marry Normal People, fuck Conversations with Friends, and kill BWWAY—mostly because I haven't read it yet but I was told that the characters are boring and hard to get attached to so now I want to read it even more, but until then, RIP.

Who’s That Girl?

For most people (and young women, in particular) on TikTok, the That Girl trend has become almost suffocatingly unavoidable.

In the midst of tarot card readings and things that are only funny if you have insomnia and are existing on less than four hours of sleep (aka my For You Page), there are all these girlies who are more often than not extremely thin, extremely white, and extremely militant about waking up at 5:30 am to workout and journal. They also somehow have the disposable income to wash their hair with Olaplex products, drink a chlorophyll smoothie before their matcha, and eat fresh organic fruit… like the expensive bananas at Trader Joe’s.

They’re not necessarily wrong to do so—they’re just doing so an awful lot these days.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The #ThatGirl hashtag now has over four billion (yes, with a B) views on TikTok and is for some reason the it thing to do to revolutionize your life in 2022. An extension of the “romanticizing your life” trend, the That Girl trend began innocently enough but has become something vaguely threatening—join us if you want to be successful seems to be the unsaid messaging of these videos.

With that said, the in-crowd out-crowd energy of That Girl feels vaguely reminiscent of women’s trends of yore. I asked Erin to elaborate:

Emily: What is the That Girl trend and is it a new phenomenon? If not, what iteration is the trend currently in?

Erin: I wouldn’t say it's a new phenomenon, but I think the era of social media changed the desirability of it. It’s the shift from admiring That Girl and slowly adopting trends, to wanting to present as That Girl and habitually posting your new lifestyle.

The That Girl of the 2010s was the chill girl: she was one of the guys, and she didn’t need a fancy latte—just a black coffee. Oh, and she really, really, loved pizza. Have you heard of the Arctic Monkeys? No? Well, she has.

When I hear about That Girl today, I think oversized blazer, glowing skin, sleek ponytail. She’s a local at her independent coffee shop (where she gets an oat milk latte), is well informed about social and political issues, has color-coded day planner, loves a night out on the dance floor after ABBA karaoke but wakes up early without a hungover before she journals, makes a smoothie, and goes on a hot girl walk.

Those are very specific examples but in general, “That Girl” is someone who prioritizes herself. She prioritizes balancing taking care of her mental and physical health, and her relationships, and she puts effort into indulging in her favorite things. She really knows herself and she really wants you to think this is her daily routine.

I think this is what our That Girl looks like right now because it’s what we’re all craving. The past two years have forced us to pay attention to who we are and what we need and create new lifestyle habits. We're all so desperately trying to figure out how to balance work, life, and adulthood—and have it all.

That Girl has figured it out and she has it all—do you?

I won’t lie: I’m a little scared of That Girl. Of course, there’s a part of me that wants to be her, but at what cost? For starters, waking up consistently at 5:30 am is just not feasible when I have to medically induce my sleep nightly. For another thing, I’m ridiculously competitive and could see myself ruining my sanity in the pursuit of becoming the ultimate girl.

A thought piece from Maya Sargent in Glamour UK about the trend touches on this point:

We can look at how aesthetics manifest to understand the toxicity that can come from them. Trends do not self-perpetuate; they rely on traction, obsession—and most importantly—a cult following. Adherence to an aesthetic therefore often breeds competition.

That’s a bit darker than just morning yoga and manifestation—could That Girl be belying something more sinister? I asked Erin:

Emily: What are the implications of this trend? Would you consider it more benign or harmful to young women on the Internet?

Erin: As I mentioned, That Girl is someone who prioritizes herself but it’s also someone who wants to present on social media like they are prioritizing themself—how people "prioritize" taking care of themselves has more recently taken a dip in the "toxic wellness" pool.

I definitely think there are people who present the image that they live as That Girl every day, which isn’t sustainable or realistic. I think if young women choose to believe that social media content is representative of someone's daily life and well-being then yes, it would be harmful.

I will say, in the early 2010s, there was an “other” or a direct foil to That Girl (the one who just wanted pizza) and that felt hurtful, almost mean. It became lame to enjoy things unless they were deemed worthy in the eyes of men, and everyone wanted to be so painfully relatable.

Whether it’s real or not, it currently feels like That Girl could also be anyone working towards the aesthetic—and in that way, it feels less harmful.

The understanding of just how toxic the "she's not like other girls" trend was has created this counter balance of women supporting other women and accepting that it's okay, even cool, to be like other girls. The culture of "you're either with us, or against us" feels like it is a thing of the past—exclusive social groups from teen movies past (think: the lunch tables in Mean Girls) have become so diluted as we move towards a culture of acceptance.

When I am fed the That Girl content online, I see a discourse surrounding incremental change. It's not predicated on you either are That Girl, or you aren't; being That Girl isn't a finish line—it's small choices you can make everyday.

Erin’s answer made me stop and think that while I definitely do not fit the mold of the aforementioned stereotypical That Girl—the one I am still very much afraid of—I kind of have become my own version of her: I have my color-coded book stacks resting under my aesthetic wall collage, my cat sleeps on the orange blanket that creatively mismatches the pink couch, and, if I should be so bold to share online, I now make a mean chia seed pudding.

Most notably, I am a proud Sally Rooney girl. Does that make me… That Girl?

Welcome to the Real Metaverse

It’s hard for me to admit that I was actually with the times when I first read Sally Rooney at the start of the pandemic.

Operating under the assumption that everyone has at least heard of our girlboss queen at this point, we’ll dive into some of the Rooney-uances: like fellow Goodreads Girlie beloved author Ottessa Moshfegh, there are layers to consuming Sally’s writing. On the surface, it’s absolutely beautiful—it’s literary, but accessible. It’s moody, but sexy. The books have no clear plot, but contain volumes.

The next level down is the connections readers create with her characters who are the idealized versions of real-life messy-ass people with complicated emotions and terrible interpersonal communication.

Just below that, Rooney’s Marxist ideologies are clearly infused into her words. As journalist Fionnán Sheahan said in a review of the Hulu adaptation of Normal People,

“The author of Normal People is a self-professed Marxist... her politics seeps through her writing. It's no accident the central protagonists of the book that has captured the nation's imagination are the rich girl living in the mansion and the poor boy whose mother works as her family's cleaner. The TV version glosses over the discussions around The Communist Manifesto and the feminist bible The Golden Notebook.“ (X)

Regardless of what draws you into her work and world, it’s undeniable that Rooney is wildly popular and has an effect on why reading has become That Girl trendy. I asked Erin exactly that:

Emily: What are your thoughts on the Sally Rooney-fication of books and reading in general? Did Sally Rooney make reading trendy again?

Erin: I'm not so sure that reading has become trendy as much as having books has. I think Rooney was the perfect poster child for the book club girlies. It felt like an “if you don’t get it, you don’t get it” type of book—the cover almost became an iconographic symbol for being in the know.

I think once things like BookTok or Instagram book clubs took off during Covid, book covers became icons for community—being associated with that icon meant that you had community and that were balancing work and pleasure. Carrying a book, reading in public, and having a bookshelf became really trendy because it looks like you’re prioritizing personal time. And in that, knowing the popular stories like Normal People, Where the Crawdads Sing, and Such A Fun Age, became trendy and desirable in the same way that understanding all the pop-culture references in Gilmore Girls makes you feel superior.

It is hilariously ironic that even though the characters in Sally Rooney's novels are literary enthusiasts, she uses it almost as a character flaw to depict someone who hides in fiction. She has openly said: "the thing about books is that anyone can read them. There are a lot of people who probably enjoyed Conversations with Friends who are part of the system that is actively exploiting other people’s labour. I am sure there are landlords who read it and thought it was a great read. Am I happy that I have given those people 10 hours of distraction? Not really!" and I love that.

Emily: How does Sally Rooney fit into the That Girl trend?

Erin: This question made me think a lot. At first, I read it to mean Sally Rooney, the person who is an author, but then I thought about how Sally Rooney, as a name, has become synonymous with viewing life in a certain way which I think has nothing to do with Rooney herself, but the characters she writes, and the people who relate to them.

I’m going to write for both ways I read it.

Sally Rooney the author herself: As someone who was thrust onto the literary scene so young and so early in her career, she has become a Hemingway-esque representation of success. She writes characters that are relatable and that this generation connects with, because she is an active member of this generation.

Despite being a best-selling author, she still feels like this secret that only the cool girls know, and I think it’s her humility. She speaks openly about the hypocrisy of writing books that heavily criticize class and privilege while actively participating and profiting from the system.

If you are an aspiring That Girl, associating yourself with an author like Rooney makes total sense. She clearly has that “balance” that every That Girl is fighting for—she’s successful in her career, she is well educated on social issues, she knows herself and acknowledges her privilege.

Sally Rooney as an amalgamation of the characters she writes: It’s pretty common to use the name of a writer as a figurehead for the characters they write. I fall victim to this a lot—I’d say I’m such an Amy Sherman Palladino girl (second Gilmore Girls reference) to mean that I talk fast, I am stubborn, and often lead with my emotions. I have never met Amy Sherman Palladino and I have no idea if she herself should be associated with those attributes.

If someone were to self-identify as a Sally Rooney girl, it could mean two things:

1) she is analytical, well-informed about political issues, argumentative, and passionate. Those aren't just characteristics of Rooney’s female characters—all of her characters have some blend of these traits (except Normal People’s Jamie. Fuck that guy).

Or 2) they identify as the type of girl who reads Sally Rooney. This is a much more vague description to ultimately mean that they are on trend, have time to read, and can handle a book with minimal punctuations.

I would argue the That Girl trend rests on the possibility that people who self-identify as a Rooney girl could be referring to either iteration.

The layers of her work have allowed Sally Rooney to appeal to such a wide swath of people, all for opposite reasons: there are the people who want to be seen reading her books for clout, the people who like what Rooney is trying to say about society, the people who like strong literary writing regardless of who wrote it, the people who like strong literary writing because Rooney wrote it, and the people who just picked her books up one day unprompted.

There’s no one right way to a read a book, so none of these are actually any better or worse than the others (that’s for all the pick me girls in the chat who think that really getting Sally Rooney’s Marxist undertones makes them more special than everyone else, which is actually the only wrong way to read a book). But there is a wrong way to form an identity and that’s by adopting other people’s traits instead of forming your own… or is it?

We all do this to some degree: we want to know which Hogwarts house we’d be sorted into, which Sex and the City girlie we are, which book is our emotional support Sally Rooney novel. We want to see ourselves in stories so we project onto the characters in them and convince ourselves that we really are just like Frances and Nick.

But isn’t that the inverse of the That Girl trend? We see a real person and wonder why we are not living their life, essentially projecting their projection onto us. It’s this Marvel-Cinematic-Universe-Mark-Zuckerberg-tax-fraud-rebrand meta level of thought that inspired me to ask Erin:

Emily: This is such a huge question but why do we so often project onto fictional characters but then project real people online onto ourselves?

Erin: Oh man. This question makes my brain spin.

The simple answer is in the definition of “real people.” When we engage with fictional content, books, movies, TV, etc, the first concept that our brain encodes is fiction. The origins of a fictional character are authentically fiction just by virtue of existing within the medium. Even when based on a true story, our minds still identify the level of interpretation at play, which is ultimately a form of fiction.

With the foundation of this information being fictional, it is easy to have control over the narrative: I can choose which parts of that fictional character to connect with because I know somewhere, a writer took all of the traits they wanted and assigned them to this person, so I can easily do the same.

The origins of social media were predicated upon reality and connection. Controlling the narrative surrounding fictional characters is limited, but controlling the narratives surrounding your own life is boundless.

I can present whatever life I want on social media and it may or may not be reality, but because of the foundations of social media, your brain will encode that information as a possible reality OR a possible community or connection that excludes you. We project the online content we consume onto ourselves because it is, in some reality, possible. It's also easy to view it through a lens of "lack"—they have something I don't.

Damn. And I thought I was meta.

But this also touches on one of the conversations Bianca and I had two weeks ago about authenticity on the Internet. While Bianca argued that authenticity largely only exists when you’re not tying your identity to your shared content, Erin’s point begs the question: what if you’re creating an identity through your shared content?

Because of that, I once again had to ask:

Emily: Is there any way to exist authentically online?

Erin: As someone with a degree in digital studies, I can honestly say that I have never come up with an answer to this that I am satisfied with.

Overall, I think it depends on how you define authenticity. I love Brene Brown’s definition which is: “Authenticity is a collection of choices that we have to make every day. It’s about the choice to show up and be real. The choice to be honest. The choice to let our true selves be seen.”

I don’t think there is any reason that these choices can’t be displayed on social media and still be authentic. However, you have already compromised the authenticity by curating what you choose to post about your choices and you have to be reflective about why you’re posting it. You can still be authentic and seek social validation at the same time.

Final answer: I don’t know, but I think you can try.

The Girls Are Girling

With Erin’s first E4P conversation in mind, I couldn’t avoid the glaringly obvious fact that the That Girl trend is so heavily gendered—like, it’s literally right there in the name. It also is so easy to change its implication to something really degrading with absolutely minimum effort: “Oh, you’re that girl?”

I was once again brought back to the question, Can women just enjoy things in peace?, so I asked Erin:

Emily: Is it possible for young women to enjoy things without making it a personality trait? Is there something to be said about why we have a tendency to do this?

Erin: Yes totally—but why wouldn’t they want to! My personality is the sum total of the things and people that I love. Normal People came into my life when I was feeling really lost, and it did fill a small hole in my personality. As someone who has always craved fitting in and female friendships, I loved being like the other girls who read Normal People. I love anything that allows me to build community and there is nothing wrong with that.

I think the biggest problem is that we (society as a whole) criticize women for liking things that other women like. It goes back to the age old “she’s not like other girls” line of thinking which is cruel. I think for so long our society benefited from isolating women and encouraging them to have interests which serve men.

This could be a stretch, but I think women weaving their interests into their personality is a subconscious tactic to safeguard their methods of building community. No matter how physically isolated I am, I can build community with anyone who I can tell is wearing Glossier You.

Emily: Not to undercut this whole conversation but do you have an emotional support Sally Rooney book like I do? What are your general thoughts on her writing?

Erin: Normal People, 100%. It made its way into my life the day after my international long-distance relationship ended so it felt kismet. It really validated that heartbreak hurts and that I have a whole life and personality outside of being in a relationship.

As someone with a reading disability, Rooney’s disdain for appropriate punctuation makes it significantly more difficult to read, so finishing the story felt like a triumph and I felt like she was proud of me. I was so excited to read Beautiful World, Where Are You?, but my friend reviewed it saying “it’s boring, and the characters aren’t likable” to which I replied, “yeah that’s the best part.”

That is truly why I like the characters she writes: they are soft, they are real people, they over-analyze and they are sometimes hurtful. The lives of these characters are so much denser than a single plot point, a climax, or even a story arc. They are real, complex, mundane people.

Most people praise Rooney's depiction of intimacy—how characters are developed through their relationships (or lack thereof) with each other, which is beautiful—but I truly love the slow moments of characters overanalyzing how they feel. It's so human.

I have so much love in my heart for Conversations With Friends, a book I read at the exact right moment in my life, too. Like Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter or Emma Cline’s The Girls, Rooney managed to capture my innermost psyche. Even if I didn’t align with each of Frances’ thoughts, they were still somehow, magically, mine.

I even had my own That Girl moment while reading it: on a furiously hot day in May 2020, I was sitting outside reading with my mom when a sudden summer storm started. Danni Lee quickly ran inside but I stayed out, laughing in the pouring rain, because why not? I felt almost childish in my unbridled happiness in the midst of the early pandemic insanity and the bizarre uncertainty of graduating into a void.

Eventually, the rain stopped but I still haven’t shaken the giddiness that I will always associate with reading that book.

After all of this, I just had one question left:

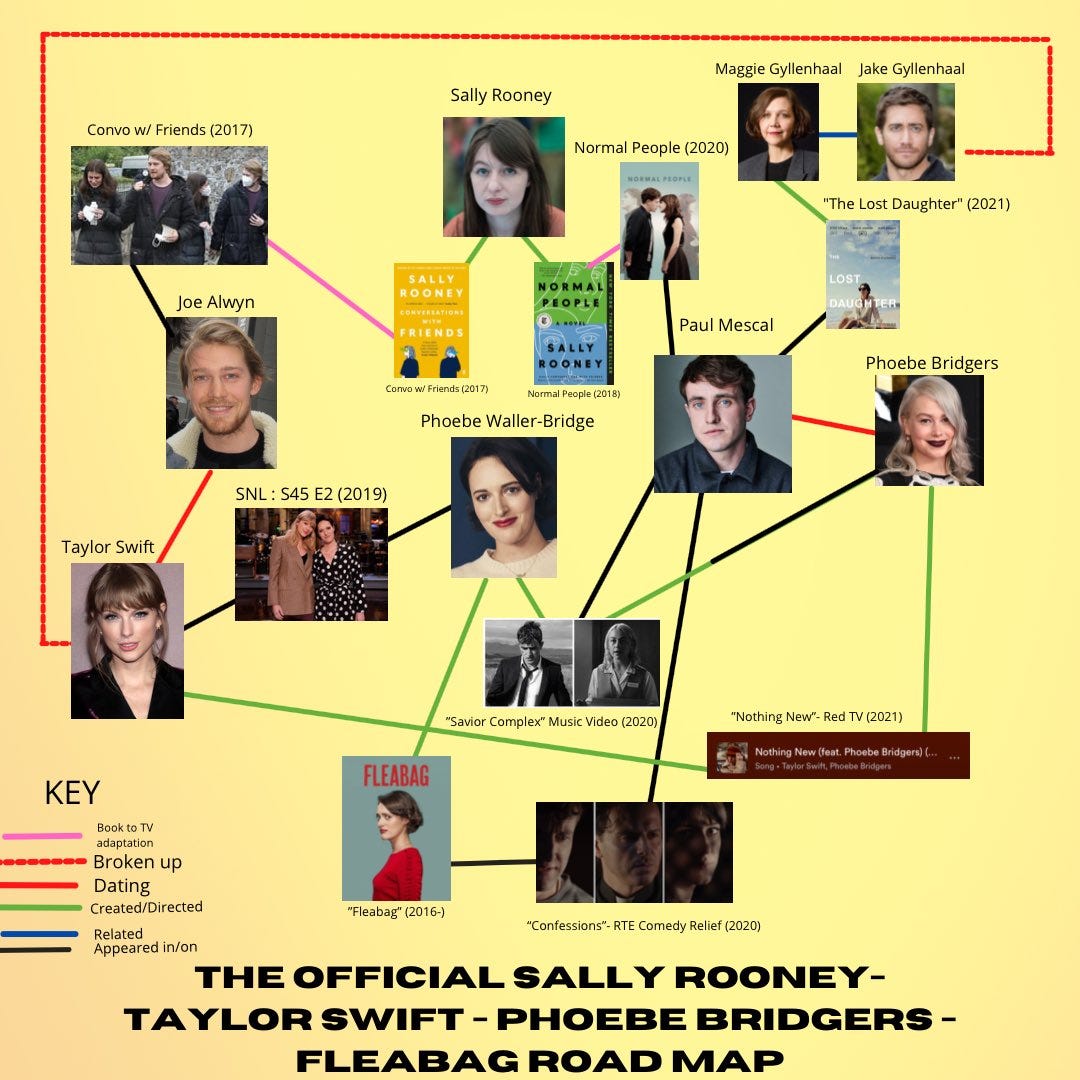

Emily: What are your thoughts on Taylor Swift being a Sally Rooney girlie and why do we not talk about that enough?

Erin: Just thought I'd throw this out there—I like to listen to Right Where You Left Me and think about Marianne and Connell.

I have no notes at this time on Taylor being a Sally Rooney girl, but can we talk about how gross it is that so much of the press surrounding CWF is about Ms. Swift’s approval of Joe Alwyn’s sex scenes—ew???

Thank you so much to Erin for always being so amazing and insightful!!! She wrote all of these while multitasking a work event and a flat tire, so I’m unendingly grateful!!!!